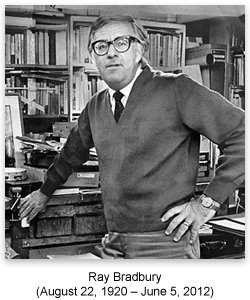

On June 5, acclaimed author Ray Bradbury passed away. I can't say I have been much affected by the loss. My relationships with most authors typically begin and end within the pages of their books. I find that delving into writers' and actors' lives — specifically the components of their political beliefs — is often a disappointing venture to complete. Yet it still saddens me that our world is no longer graced by the man's presence.

It is interesting that he descended from Mary Bradbury, a woman who was convicted and sentenced to hang in the 1600s during the infamous Salem witch trials. After such brutalities were imposed on the family, I can't tell if it's nature or nurture that Ray grew up to be skeptical of the way things were. Among Mary's other descendents is Ralph Waldo Emerson, the world-renowned individualist writer who grew up to say, “The less government we have the better.” I found out a few years ago that one of my great-great-great-great- ad infinitum grandmothers, too, was prosecuted as a witch during the Puritans' wicked trials. I can take this only as a fantastic compliment and hope that my antistate relatives were fighting the good fight with the Bradbury family, leading to the libertarian ideals I now cherish so deeply.

Bradbury's first original book, Fahrenheit 451, is a fiery testament against the censorship of opposing ideas. He maintained repeatedly that the people — not the state — were the book's antagonists, but the real enemy, more than the actual individuals in question, was their obsession with political correctness, which led to the shredding and burning of old literature in the first place. And as anyone will tell you, we libertarians typically have little patience for political correctness. It does nothing except dilute the true meaning of words and stupefies the population into apathy.

He further touches on this issue in the coda of Fahrenheit 451, spurred by editors erasing the phrases “God-Light” and “in the Presence” from his story. Bradbury writes,

There is more than one way to burn a book. And the world is full of people running about with lit matches. Every minority … feels it has the will, the right, the duty to douse the kerosene, light the fuse. Every dimwit editor who sees himself as the source of all dreary blanc-mange plain porridge unleavened literature, licks his guillotine and eyes the neck of any author who dares to speak above a whisper or write above a nursery rhyme.

It is possibly why the author found no use for this elitist attitude so frequently found in modern universities. Bradbury didn't go to college. Many claim this kind of decision turns people into economic underlings. (Ironically enough, Bradbury wrote the first draft of Fahrenheit 451 while physically underneath the UCLA campus.) The fact that the novel is now considered a staple of American literature proves that these pro-university critics were — and, frankly, still are — incorrect.

He spoke of disliking formal education in an interview with the New York Times:

I don't believe in colleges and universities. I believe in libraries because most students don't have any money. When I graduated from high school, it was during the Depression and we had no money. I couldn't go to college, so I went to the library three days a week for 10 years.

Not every libertarian is anti-university, per se, but most of us do see these overgrown institutions as the accidental offspring of government intervention. A mix of federal agencies, accreditation licenses, and obscene financial-aid packages have converted efficient trade schools into bureaucratic (and thus extremely expensive) nightmares offering courses and majors on topics unrelated to any industry needed in the market. A quick glimpse of today's public school system, I'm sure, would have shown Bradbury the dystopic stasis he hoped America would never become.

Like us, he held optimism in the people's ability to correct these problems without the dictates of the nosy politicians scavenging in Washington, DC. This hatred of the state came to light during an interview with Time magazine almost two years ago. When asked if he'd been upholding his antipolitical reputation, Bradbury responded with strong words, making sure to provide some sage advice on the potential of peaceful, loving resolutions:

I don't believe in government. I hate politics. I'm against it. And I hope that sometime this fall, we can destroy part of our government, and next year destroy even more of it. The less government, the happier I will be.… All I can do is teach people to fall in love. My advice to them is, do what you love and love what you do. Then you become free of all laws and all gravity.

Indeed. There is little more to add. It's a shame I never knew these things as I read Bradbury's books many years ago. Perhaps I would have read them more slowly, paid extra attention to certain paragraphs, and taken a deep breath afterwards to reflect on the chance that maybe, somewhere deep in the plotline, there was more than just a fantasy. The conversation with ancient writers, the nonstop rain on a distant rock, watching the earth catch on fire from the edge of Mars — we'll probably never know if these descriptions were symbols of something we'll finally understand years into the future.

But this we do know: a wonderful human being — who left behind a literary legacy of fighting for the freedom to acquire and share knowledge — passed away as Venus and the sun crossed paths; the two symbols of love and truth mark a beautiful end to a life we'll remember for a long time.

They all came out and looked at the sky that night.… There was Earth and there the coming war, and there hundreds of thousands of mothers and grandmothers or fathers or brothers or aunt or uncles or cousins. They stood on the porches and tried to believe in the existence of Earth, much as they had once tried to believe in the existence of Mars. (The Martian Chronicles)