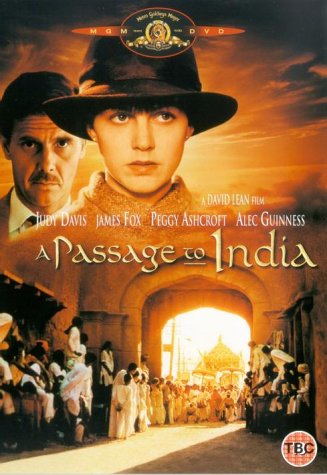

A Passage to India, by E.M. Forster [trade paperback]; also made into an award-winning film.

Perhaps the most important task of all would be to undertake studies in contemporary alternatives to Orientalism, to ask how one can study other cultures and peoples from a libertarian, or a nonrepressive and nonmanipulative, perspective.

When I asked Dr. Plauché what I should review for my first contribution to Prometheus Unbound, he suggested that I elaborate on my recent Libertarian Papers article: “The Oft-Ignored Mr. Turton: The Role of District Collector in A Passage to India.” Would I, he asked, be willing to present a trimmed-down version of my argument about the role of district collectors in colonial India, a role both clarified and complicated by E.M. Forster’s portrayal of Mr. Turton, the want-to-please-all character and the district collector in Forster’s most famous novel, A Passage to India. I agreed. And happily.

For those who haven’t read the novel, here, briefly, is a spoiler-free rundown of the plot. A young and not particularly attractive British lady, Adela Quested, travels to India with Mrs. Moore, whose son, Ronny, intends to marry Adela. Not long into the trip, Mrs. Moore meets Dr. Aziz, a Muslim physician, in a mosque, and instantly the two hit it off. Mr. Turton hosts a bridge party — a party meant to bridge relations between East and West — for Adela and Mrs. Moore. At the party, Adela meets Mr. Fielding, the local schoolmaster and a stock character of the Good British Liberal. Fielding invites Adela and Mrs. Moore to tea with him and Professor Godbole, a Brahman Hindu. Dr. Aziz joins the tea party and there offers to show Adela and Mrs. Moore the famous Marabar Caves.

For those who haven’t read the novel, here, briefly, is a spoiler-free rundown of the plot. A young and not particularly attractive British lady, Adela Quested, travels to India with Mrs. Moore, whose son, Ronny, intends to marry Adela. Not long into the trip, Mrs. Moore meets Dr. Aziz, a Muslim physician, in a mosque, and instantly the two hit it off. Mr. Turton hosts a bridge party — a party meant to bridge relations between East and West — for Adela and Mrs. Moore. At the party, Adela meets Mr. Fielding, the local schoolmaster and a stock character of the Good British Liberal. Fielding invites Adela and Mrs. Moore to tea with him and Professor Godbole, a Brahman Hindu. Dr. Aziz joins the tea party and there offers to show Adela and Mrs. Moore the famous Marabar Caves.

When Aziz and the women later set out to the cavea — Fielding and Godbole are supposed to join, but they just miss the train — something goes terribly wrong. Adela offends Aziz, who ducks into a cave only to discover that Adela has gone missing. Aziz eventually sees Adela speaking to Fielding and another Englishwoman, both of whom have driven up together, but by the time he reaches Fielding the two women have left. Aziz heads back to Chandrapore (the fictional city where the novel is set) with Fielding, but when he arrives he is arrested for sexually assaulting Adela. A trial ensues, and the novel becomes increasingly saturated with Brahman Hindu themes. (Forster is not the only Western writer to be intrigued by Brahman Hinduism. Ralph Waldo Emerson and William Blake, among many others, shared this fascination.) The arrest and trial call attention to the double-standards and arbitrariness of the British legal system in India.

Rule of law was the ideological currency of the British Raj, and Forster attempts to undercut this ideology using Brahman Hindu scenes and signifiers. Rule of law seeks to eliminate double-standards and arbitrariness, but it does the opposite in Chandrapore. Some jurisprudents think of rule of law as a fiction. John Hasnas calls rule of law a myth. Whatever its designation, rule of law is not an absolute reality outside discourse. Like everything, its meaning is constructed through language and cultural understanding. Rule of law is a phrase that validates increased governmental control over phenomena that government and its agents describe as needing control. When politicians and other officials lobby for consolidation or centralization of power, they often do so by invoking rule of law. Rule of law means nothing if not compulsion and coercion. It is merely an attractive packaging of those terms.

British administrators in India, as well as British commentators on Indian matters, adhered in large numbers to utilitarianism. Following in the footsteps of Jeremy Bentham, the founding father of utilitarianism, these administrators reduced legal and social policy to calculations about happiness and pleasure. Utilitarianism holds, in short, that actions are good if they maximize utility, which enhances the general welfare. Utilitarianism rejects first principles, most ethical schools, and natural law. Rather than couch their policymaking in terms of happiness and pleasure, British administrators in India, among other interested parties such as the East India Company, invoked rule of law. Rule of law manifested itself as a concerted British effort to discipline Indians into docile subjects accountable to a British sovereign and dependent upon a London-centered economy. The logic underpinning rule of law was that Indians were backward and therefore needed civilizing. The effects of rule of law were foreign occupation, increased bureaucratic networks across India, and imperial arrogance.

Murray Rothbard was highly critical of some utilitarians, but especially of Bentham (see here and here for Rothbard’s insights into the East India Company). In Classical Economics, he criticized Bentham’s opinions about fiat currency, inflationism, usury, maximum price controls on bread, and ad hoc empiricism. Bentham’s utilitarianism and rule of law mantras became justifications for British imperialism, and not just in India. A detailed study of Hasnas’s critique of rule of law in conjunction with Rothbard’s critique of Bentham could, in the context of colonial India, lead to an engaging and insightful study of imperialism generally. My article is not that ambitious. My article focuses exclusively on A Passage to India while attempting to synthesize Hasnas with Rothbard. Forster was no libertarian, but his motifs and metaphors seem to support the Hasnasian and Rothbardian take on rule of law rhetoric and utilitarianism, respectively. These motifs and metaphors are steeped in Brahman Hindu themes and philosophy.

Forster wrote A Passage to India over the course of several years. He visited India twice. His trips there were long and formative. While in India, Forster developed a certain fondness for Brahman Hinduism and its emphases on unity and transcendence. These emphases, perhaps misinterpreted by Forster, found their way into the novel where they stood — and stand — in contradistinction to rule of law. Forster’s understanding of Brahman Hinduism may not have been sophisticated, but his understanding informs the novel and calls into question the underlying assumptions of rule of law rhetoric.

Forster wrote A Passage to India over the course of several years. He visited India twice. His trips there were long and formative. While in India, Forster developed a certain fondness for Brahman Hinduism and its emphases on unity and transcendence. These emphases, perhaps misinterpreted by Forster, found their way into the novel where they stood — and stand — in contradistinction to rule of law. Forster’s understanding of Brahman Hinduism may not have been sophisticated, but his understanding informs the novel and calls into question the underlying assumptions of rule of law rhetoric.

It would do little good to insist that Forster was a libertarian or that his novel promotes libertarianism. But it is useful to consider how his novel sheds light on libertarian ideas and shares the libertarian disdain for imperialism and economic nationalism. Mr. Turton is pivotal to this consideration because of his position as a cultural mediator. As a district collector, he is supposed to be the linchpin holding British and Indian societies together. Yet because of cultural and philosophical incompatibility, the British and Indian characters cannot get along — that may be an understatement — and Turton fails in his efforts to treat British and Indian characters equally. Turton is, despite himself, always a partisan of British interests.

A Passage to India suggests that government intervention or takeover of foreign peoples will lead to an unsustainable system — or else a system that can only be sustained through violence, as the Amritsar Massacre, a true event that probably influenced Forster, indicates. The book also shows that rule of law, bound up in utilitarianism, is a fictional construct leading down the road to cruelty. And cruelty is never a good thing.

Comments on this entry are closed.

Konrad Graf January 28, 2011 @ 11:17 am | Link

An excellent point that libertarian-sounding language does not indicate authenticity. Good-sounding ideas and phrases are regularly co-opted–repurposed—to serve other, quite different, ends. “The rule of law” usually isn’t. The simple test is: who has the exemptions to the consistent application of a given rule? If ‘do not agrees,’ who is nevertheless still officially allowed to aggress?