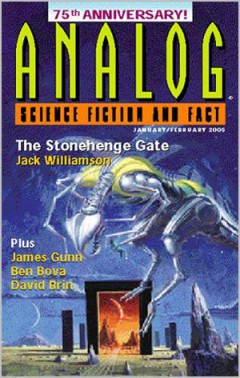

If you’ve ever wanted a peek inside the mindset of the utilitarian pragmatist and unabashedly statist, then you would do well to read or listen to David Brin’s novelette “Mars Opposition.” Begun in 2003 with the launch of the Mars Exploration Rover Mission (MER), and originally published in Analog in January 2005, “Mars Opposition” has been republished in audio format in episode 298 of StarShipSofa (free). It is a well-written tale, though predictable and unsubtle, and is superbly narrated by Dave Robison. Unfortunately, Brin uses the story as a vehicle for riding some of his political hobbyhorses:

- defending government and its officials from antigovernment criticism,

- making government smarter with the help of the technocratic elite (such as himself),

- and smearing libertarians as dogmatic, asocial creatures who are clueless about the human condition.

Fair warning, what follows is spoiler-ridden.

“Mars Opposition” opens at Cape Canaveral with the landing of a strange spaceship. What follows is an even stranger first contact with 50-odd beings who claim to be Martians. They each bear a long list of human names and offer payment in exchange for being given the location of one person on the list. When one of these people — Bruce Murray, one of the founders of the Mars Planetary Society — happens to be present, the Martian looking for him promptly walks over and “shoots him dead.” Before long, the Martians are scattering in all directions, each hunting for the next name on their list.

Why are Martians killing these people who all happen to be space enthusiasts? The unidentified narrator (from here on referring to the POV character, not Dave Robison) eventually figures everything out and explains it to us as events unfold. As fresh and interesting as this take on a first contact story is, I won’t dwell on it and will instead turn to examining Brin’s political message.

Brin himself describes “Mars Opposition” as a creepy campfire tale. That would make the Martians the boogeymen of the story. And the Martians — the boogeymen — are, as the narrator calls them at the end, ultimate libertarians.

How are they portrayed and described within the narrative? Well, since they are so powerful and advanced, each Martian is an atomistic individual, almost entirely autonomous and self-sufficient. They interact with each other only briefly by forming temporary contractual relationships in order to pursue well-defined, concrete goals that neither party can accomplish on his own. Any socializing beyond this is a waste of time and all social interactions must involve an exactingly measured quid pro quo. They are traders you see, exchanging meticulously measured values.

The Martians at first seem to favor a restitution-based form of justice. They seem to not even require a third-party arbiter to resolve disputes, each readily compensating another for any wrongdoing when formally accused. But we learn through the narrator as the story progresses that the Martians consistently inflict a very precise proportional punishment when attacked by humans.

You’re probably thinking there’s a catch, and there is. Not all libertarians see even proportional punishment in retaliation for a rights violation as justice served, but even those who do will have a problem with the way the Martians apply it. They think so highly of themselves, you see, and so little of human life, that minor annoyances to them justify inflicting severe bodily injury on a human. The death of a single Martian justifies killing tens of thousands of human beings if they are in any way involved. Suffice to say that being an involuntary taxpayer won’t absolve you. That is proportional justice to them.

The Martians cannot understand the human need and propensity to form more durable social relationships that lack an explicit accounting of mutual benefit. They have no concept of the state. They cannot conceive of cultural differences, having been monocultural themselves for hundreds of millions of years. They are rigid, asocial, crass businessmen because — thanks to their godlike power and lack of human frailty — they can be.

This is one false dichotomy crafted by Brin, the caricature of the principled libertarian juxtaposed with the realistic explanation of the human condition presented by the narrator. Another false dichotomy presented by the narrator involves the two stark options for dealing with the Martians. Humanity can either stubbornly pursue a noble resistance and be virtually wiped out by the Martian invaders. Yes, we primitive humans are explicitly likened to the American Indians and the superior Martians to white European conquerors. Or, we can learn from the Indians’ mistake and pursue a more pragmatic approach, though it be a necessary evil, which is that we should sacrifice a relative few (hundreds of thousands) in order to save the many (billions).

There really is no other way. If the human race is to survive, we must not resist. Noninterference will result in many fewer lives lost than an unwinnable total war. But wait…that’s not pragmatic enough. We can do better. So the narrator urges the US government to not merely refrain from interfering with the Martians’ mission of revenge for deaths somehow caused by MER but to help them find the people on their list who they think are responsible. Why not trick the Martians into compensating us for each human life? Yes, we should take advantage of their trader mentality in order to extract as much advanced scientific and technological information as possible as payment for our help. We can not only survive as a species but bootstrap our technical know-how, while avoiding the Martians’ atomistic fate and retaining our humanity.

Sorry, but I don’t think aiding and abetting the murder of hundreds of thousands of human beings is conducive to retaining one’s humanity. Apparently, Brin bought Spock’s Vulcan logic in Star Trek II and failed to internalize Kirk’s human rebuttal in Star Trek III: “The needs of the one…outweigh the needs of the many.” A pragmatic utilitarian calculus is not the way to foster empathy and deep, lasting social relationships. Spock, at least, sacrificed only himself.

It is easy to construct hypothetical scenarios that present the reader or interlocutor with only two undesirable courses of action or outcomes, one more undesirable than the other. Academic philosophers do this all the time, “pumping our intuitions” in order to steer us toward their preferred ethical conclusions. Every detail is carefully selected, yet the scenarios are invariably underspecified compared to real-world situations. They also approach ethical theorizing from the wrong direction, attempting to arrive at or justify general principles from highly unusual edge cases rather than attempting to determine general principles for everyday living and then figuring out how they apply to extreme situations.

I don’t think the real world presents us with only two bad options very often, if ever. There is usually another, better way that’s not as obvious. If we are clever enough and wise enough, and do not abandon our principles at the first sign of difficulty, we can find it. In the unfortunate event that we come up short, however, I believe that it is better to suffer injustice than to commit it. The central question of ethics is not what rules should I follow (deontology) or what consequences should I promote (consequentialism), but what kind of person should I be (virtue ethics)? Do you want to be the kind of person who helps to murder innocent people in order to gain scientific knowledge?

It is not enough for Brin to smear libertarians with his confused caricature and to promote a utilitarian pragmatism. He also promotes an idealized image of government officials as well-intentioned people who must be pushed to do the pragmatic thing by a self-sacrificial technocratic elite. Here Brin presents another false dichotomy. He wishes to hold up what he sees as a more realistic depiction of government officials against the pitiless, petty-tyrant stereotype that makes for such good villains in stories. In attempting to defend government officials from lazy and subversive writers, Brin goes too far in the other direction and draws an unrealistically noble picture. Yes, not all government officials are evil, power-hungry tyrants. But, as a cursory look at history reveals, while often well-intentioned, they need little outside encouragement to pursue the pragmatic course of action. Pragmatism is required by the job, and many, most, whatever, will readily pursue the pragmatic course, sacrificing some (but rarely themselves) for the benefit of others, with the best of intentions.

Now let us turn our critical eye, finally, on Brin’s self-sacrificial technocratic elite. Were it not for the unidentified narrator carefully explaining everything to dull-witted government officials and manipulating the situation in order to pressure them into accepting his proposed course of action, they would have chosen the path of noble resistance and gotten all of humanity killed. Someone had to make the decision to commit the necessary evil, and taint his soul or mar his character in the process.

Someone had to be the “special, darker kind of hero.” Seriously, Brin thinks this is heroic; those are his actual words. A character much like the Operative in Serenity, who murders whoever his government tells him to in order to “make better worlds,” who knows he is a monster because of it and is therefore unfit to live in said better worlds, is heroic. He may not kill people with his own hands like the Operative, but his reasoning is the same and he is an accomplice.

The narrator knows he is 112th on the Martian’s list and is therefore promoting a course of action that will lead to his own death. I suppose this is part of what makes him a hero for Brin, though Brin made sure he was going to die either way. Like the Operative, he will not get to live in the better human worlds that his evil acts will supposedly help create. It’s awfully convenient too that he won’t have to live with what he has done. The story ends with him hoping government officials get something cool in exchange for his life. How heroic.

So tell me, those of you who managed to listen all the way through “Mars Opposition” (I listened to it twice), is my assessment fair and accurate? What has been your experience reading or interacting with David Brin?

Comments on this entry are closed.

Andy Cleary July 20, 2013 @ 12:34 pm | Link

“I don’t think the real world presents us with only two bad options very often, if ever. There is usually another, better way that’s not as obvious.”

Thank you. This is exactly right. The way I tend to express this is in terms of “uncertainty”: these hypotheticals are always expressed as if somehow you can be *certain* of the two extreme choices, that those are the only possibilities, and that they are 100% reliable. In general, I claim, this can never be true, because *all* predictions must have *some* uncertainty (and a choice about what action to take involves predictions about the consequences of those actions). But more to the point: it’s often extremely obvious without invoking philosophy. If I’m given a hypothetical about some nuclear terrorist and my “only choices” are to torture him or to let millions die, the implication is that somehow *I have to trust the terrorist*. Really? Some terrorist comes in and tells me he has planted a nuclear bomb, and I’m supposed to believe that this *must* be true? Anyone who would be willing to kill millions is probably not beyond a little lying here and there, either.

It’s just a small example but basically I reject these false dichotomies.

(The subject of “virtue ethics” vs “consequentialism” I may have to defer on, but let’s stick to the many things with which I agree in this review. 😉 but fwiw, you’re rejecting the false dichotomy, IIUC, based on virtue ethics, while I am doing so on consequentialism. Different process, and we can argue about that, but at least the same result.)

Geoffrey Allan Plauché July 20, 2013 @ 6:22 pm | Link

Good points, Andy.

To clarify, virtue ethics is only one of the reasons I reject false alternatives such as Brin presents. That sentence was meant more to explain the immediately preceding one about about suffering versus committing injustice.

umbrarchist July 20, 2013 @ 3:45 pm | Link

Libertarians deserve all of the smearing they can get. Double-entry accounting is 700 years old but none of them can suggest that it be mandatory in the schools. But then neither can the socialists.

Mike DiBaggio July 20, 2013 @ 10:30 pm | Link

Not in the interests of being fair to Brin, but I feel compelled to say that I’ve run into a fair amount of self-described libertarians who I would describe as ultra-atomistic.

But I can hardly think of a more atomistic attitude than the one Brin champions in this story. One must suppress not only the innately human concern for justice, but also empathy and compassion for his fellow man, to accept this course of action.

Fabulously unrealistic lifeboat scenarios are the sine qua non of utilitarians. It is only in these unbelievable contexts that normal people can look at their ‘solutions’ and not immediately see them as wicked and unjust.

Geoffrey Allan Plauché July 20, 2013 @ 11:55 pm | Link

Mike,

There are some, but they’re hardly representative of the libertarian movement as a whole or libertarianism as a political philosophy. They certainly don’t match my libertarianism! 🙂

Fully agreed on your other points.