Good things come to those who wait, the old adage goes, and the world has waited a century for Mark Twain’s autobiography, which, in Twain’s words, is a “complete and purposed jumble.” But this 760 page jumble is a good thing. And well worth the wait.

Twain, or Samuel L. Clemens, compiled this autobiography over the course of 35 years. The manuscript began in fits and starts. Twain, while establishing his legacy as a beloved humorist and man of letters, dashed off brief episodes here and there, assigning chapter numbers to some and simply shelving others. In 1906, he began making efforts to turn these cobbled-together passages into a coherent narrative. He even met daily with a stenographer to dictate various reflections and then to compile them into a single, albeit muddled, document. The result was a 5,000 page, unedited stack of papers that, per Twain’s strict handwritten instructions, could not be published until 100 years after his death.

Twain, or Samuel L. Clemens, compiled this autobiography over the course of 35 years. The manuscript began in fits and starts. Twain, while establishing his legacy as a beloved humorist and man of letters, dashed off brief episodes here and there, assigning chapter numbers to some and simply shelving others. In 1906, he began making efforts to turn these cobbled-together passages into a coherent narrative. He even met daily with a stenographer to dictate various reflections and then to compile them into a single, albeit muddled, document. The result was a 5,000 page, unedited stack of papers that, per Twain’s strict handwritten instructions, could not be published until 100 years after his death.

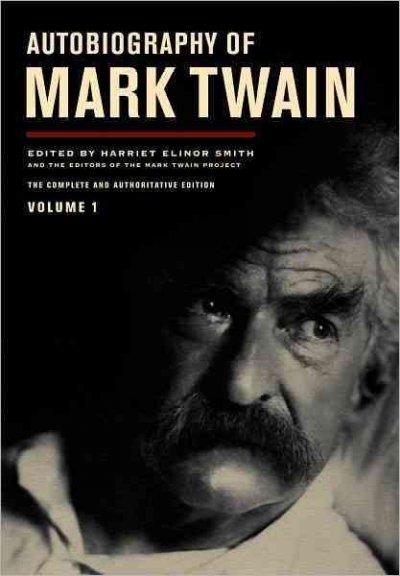

To say that we’ve waited a century to view this manuscript is only partially accurate because pieces of the manuscript appeared in 1924, 1940, and 1959. But this edition, handsomely bound by the University of California Press, and edited by Harriet Elinor Smith and others of the Mark Twain Project, is the first full compilation of the autobiographical dictations and extracts to reach print. The editors, noting that “the goal of the present edition [is] to publish the complete text as nearly as possible in the way Mark Twain intended it to be published before his death,” explain that “no text of the Autobiography so far published is even remotely complete, much less completely authorial.” The contents of this much-awaited beast of a book, then, are virtually priceless, and no doubt many of the previously unread or unconsidered Twain passages will become part of the American canon.

Stark photographs of the manuscript drafts and of Twain and his subjects — including family members and residences — accompany this fragmentary work. The lively and at times comical prose is in keeping with the rambling style of this rambling man whom readers have come to know and appreciate for generations. Would we have expected any less?

Perhaps the best part of this work is that one can pick it up and, with a few quick page flips, enjoy entire stories replete with Twain’s delightful quips and puns. Because the narrative, as it were, remains a collection of disconnected anecdotes, readers easily can pick up and put down the book as necessary — read a passage or two before bed, say, or sneak in some satire during the lunch break.

That does not mean this book is not scholarly. It is. The editors have taken pains to footnote and cross-reference, to contextualize and explain. One wonders whether Twain would have appreciated the academic flavor the editors have given the book, but then again, Twain probably would’ve been happy just knowing that he’s still in the limelight, still drawing chuckles from the masses and bashful blushes from the smug and pious.

The chummy yet cantankerous Twain would have appealed to contemporary libertarians in many respects — Jeffrey Tucker, for instance, has written on Twain’s radical liberalism — although that appeal would depend on who’s defining libertarianism, why, and how. Twain decried American military interventions abroad, in particular in the Philippines and Cuba, and his autobiography expresses exasperation over Washington’s war policy. Twain sympathizes with a “tribe of Moros,” for instance, that is “bitter against us because we have been trying for eight years to take their liberties away from them.”

Twain cloaks his account of the Moros with sarcasm: “The official report stated that the battle was fought with prodigious energy on both sides during a day and a half, and that it ended with a complete victory for the American arms. The completeness of the victory is established by this fact: that of the six hundred Moros not one was left alive. The brilliancy of the victory is established by this other fact, to wit: that of our six hundred heroes only fifteen lost their lives.” This account leads Twain to refer to the American troops as “Christian butchers,” and to bark that the victory “would not have been a brilliant feat of arms . . . even if Christian America, represented by its salaried soldiers, had shot them down with Bibles and the Golden Rule instead of bullets.”

One thing, libertarians, is for sure: Twain did not share a Kinsellaesque disdain for intellectual property rights, as made clear by the 100 year freeze on the publication of this autobiography. IP notwithstanding, perhaps the most libertarian thing we can say of Twain is that he was a rugged individualist whose political inconsistencies reflect freethinking rather than commitment to groupthink or sycophancy. There is, I think, much wisdom to be had in Twain’s go-it-alone style.

Twain, like Ayn Rand, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Jack London, is one of those figures that the intelligentsia cannot seem to bury or dismiss despite concerted efforts to do so. Many a critic has condescended to Twain’s work only to make himself look, well, foolish. That’s because the homespun and folksy Twain packs quite the intellectual punch with his powerful and conversational prose. And because, even in death, Twain speaks to us like a redneck rascal who is, despite himself, smarter than us all.

In an age when canonicity is considered dubious, Twain persists in the American imagination as a literary giant. Faulkner called Twain the “father of American literature.” If Faulkner was right, then we owe a great deal of thanks to the editors of this volume, which tells us much about our father — who probably ain’t in heaven — that we did not know before. Kudos to the editors, and thanks above all to you, Mr. Twain. Wherever you are. It was well worth the wait.