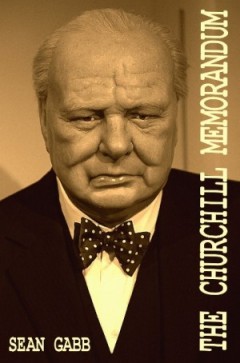

I recently read The Churchill Memorandum, by English libertarian Sean Gabb. I devoured most of it on a transatlantic flight, and finished the last bit on terra firma. I tend to like thrillers (some favorite authors include Nelson DeMille and, of late, Cherie Priest, author of Bloodshot); alternate history (e.g., Harry Turtledove, Brad Linaweaver’s Moon of Ice, L. Neil Smith’s The Probability Broach); and books with libertarian themes or influences (L. Neil Smith, Ayn Rand, Henry Hazlitt, Brad Linaweaver, Victor Koman, J. Neil Schulman). So it’s no surprise I enjoyed The Churchill Memorandum, which is very well written and which combines all three features (full disclosure: Gabb is a friend).

The novel is set in 1959, in an alternate history in which Hitler died in a car accident in 1939, thus averting WWII and changing the course of history. Gabb’s libertarian influences — he’s the head of the UK Libertarian Alliance — as well as his deep historical knowledge, are evident throughout the book. The novel depicts amazing technological progress — some of it rivaling or exceeding 2011 levels — in 1959, since WWII did not occur to sap away the economic strength and entrepreneurial innovations of tens of millions of individuals who would otherwise have been eviscerated in state war. So in 1959 there are magnetic bullet trains, home energy generators, and many other seemingly fantastic innovations.

The story follows the adventures of one Anthony Markham, a Churchill historian who, on a trip to the now-fascist police-state and isolationist America to research the Churchill archives at Harvard, stumbles across an explosive document that purports to document secret pacts that changed the course of American and world history. This leads to an intriguing geopolitical thriller informed by the author’s libertarian views. It is told in first person point of view (POV), my personal favorite for thrillers (and other novels) since it forces the narrator to show not tell, and not to omnisciently cheat and reveal details the protagonist would not know. Gabb’s ambivalent and somewhat bipolar English attitude towards America — at once a great power and friend of England, and a schizophrenic and dangerous destroyer of the ancient European order and institutions — is present throughout; and as a skeptic of the American mythos myself, I really enjoyed this foreign perspective. (Gabb recently presented a talk on “The Case Against the American War of Independence.”)

To explain the presence of the above-mentioned presence of a variety of technical innovations in 1959 that in the real world did not occur till decades later, Gabb has his protagonist Markham discuss with historian Michael Foot, one of the villains (in reality Foot was a Labour MP), what would have happened by, say, 1934, had WWI — the Great War — not occurred:

“The war broke out in 1914,” I began. “We are now in 1959. … I suggest that it’s too long now to say what would have happened if Princip’s gun had misfired at Sarajevo.

“Let’s take a shorter time. Let’s not assume 1959, but 1934, which is twenty years after a Great War that never happened. What might we have seen then? Some things, no doubt, would have happened anyway, and were only accelerated or retarded by the War. Among these must be the emancipation of women, and universal suffrage, and Irish Home Rule, and the decline of France as a great power, and the rise of Japan. You can add to this the development of radio communications and the simplification of clothing.

“We can also be more certain about the things that wouldn’t have happened. Obviously there wouldn’t have been the violent death, by 1923, of between ten and twenty million people. … The American genie would not have been so abruptly summoned from its bottle — and then so brutally stuffed back in. There would have been no Great Depression. Music and the arts wouldn’t have gone through that long descent into freakishness. We’d probably not have continued so long up the dead ends of the distributed power you like so much, or of oil power, or of aeroplane development. Hitler would never have got his statues put up all over Germany and its Eastern Territories. Lenin … would have died in Switzerland of tertiary syphilis. Stalin would have been caught and hanged for bank robbery.

“Turning to what might have happened is rather hard, even just looking at 1934. But, if most of the millions who died in or because of the Great War would otherwise have passed unmemorable lives — and there’s nothing bad about that! — there must have been other Beethovens and Pasteurs and Edisons who would have enriched mankind. Without their early deaths, we might, by 1934, have been roughly where we are now. The tuberculosis and polio vaccines might have been developed twenty or thirty years earlier. The development of the cancer vaccines might not have had to wait until now to be at the testing stage. The non-development of certain technologies would have been balanced by the earlier development of other technologies — and even the development of some that are as yet unknown.

“I suppose I should add that the non-occurrence of known evils does not mean that other evils would not have taken their place. Perhaps, without the Great War, all manner of other bad things would have happened in its place. It requires a leap of faith to say it — but I do believe that, but for the Great War, mankind would have been far better off by 1934 than it was.”

By this clever device — having a character in the alternate world of 1959 in which there had been no WWII speculate on what his world might have looked like twenty years after the Great War did not occur — Gabb neatly explains why his alternate 1959 differs in so many bizarre ways from the real 1959: many technologies are far ahead, such as magnetized bullet trains; while others are behind — blimps or zeppelins appear to be used more than jumbo jets, since airplane technology did not get the artificial boost it got in the real world due to WWII.

The passage is also informed by the libertarian free-market view that humans are our most precious resource. One of the tragedies of war is not only the lives lost, but the cultural and scientific contributions to humanity and society many of these victims would otherwise have made. This exchange also shows why Gabb set his novel in 1959, instead of, say, 2011 — predicting the effects of Hitler’s 1939 death would be too speculative more than about twenty years out. So the 1959 setting makes perfect sense to explore the consequences of a WWII-free world.

In addition to a rogues’ gallery of various early 20th-century politicians and leftists playing a role in the plot, Ayn Rand also makes an appearance (jailed in the United States for smuggling from Canada) as do her disciples Alan Greenspan (arrested when trying to emigrate using a false ID) and Nathaniel Branden (leading some kind of underground resistance in England). And a rising star in British politics, young Margaret Roberts (later Thatcher), is mentioned near the end of the novel. And the names Mises and Hayek are floating around — Mises as Goering’s Finance Minister, and Hayek in some high-level government position in Germany as well.

My only quibbles: a few typos (missed quotation marks here and there, mainly); a tendency of some of the bad guys to speak overly melodramatically and floridly, like Bond villains; and a profusion of dropped names from the post-WWI English political set, presumably most of them real, but due to my American ignorance and declining desire and ability to keep going to Wikipedia for elaboration (I was on a plane over the Atlantic, remember, for most of this, where Internet connectivity is unavailable).

But the action is crisp, the imagined alternate world intriguing. Recommended for those who like, say, any two of my troika above: thrillers, libertarian fiction, alternate history.

Comments on this entry are closed.

google.com/accounts/o8… June 9, 2011 @ 3:56 am | Link

Dear Stephan,

You did mention a “small review.” This, however, is an impressively long and searching review. It is also very generous. Many thanks for having taken the trouble to write it.

You do implicitly mention the novel’s main defect. This is that the biggest market for alternative history fiction is in America, and this novel is aimed at British readers who know, or have lived through, the actual world since 1945. Since all the reviews have been good – even those by people I haven’t met – I don’t think it’s vain to say that the novel does work well in its own artistic terms. But I do accept that, from the marketing point of view, I might have chosen a less obscure theme.

Fortunately, I published this myself, so the cash return has been acceptable. A mainstream publisher might have found a wider market – or might have reached much the same market as I have, and left me with a far less acceptable return.

I need to bear this in mind, as I am about to start work on another fantasy novel that also involves England, but might find more readers in America. I must bear in mind the sad fact that England is no longer the focal point of our civilisation.