Anyone who read Dr. Seuss’s The Lorax as a kid might dread the movie version. No one really needs another moralizing, hectoring lecture from environmentalists on the need to save the trees from extinction, especially since that once-fashionable cause seems ridiculously overwrought today. There is no shortage of trees and this is due not to nationalization so much as the privatization and cultivation of forest land.

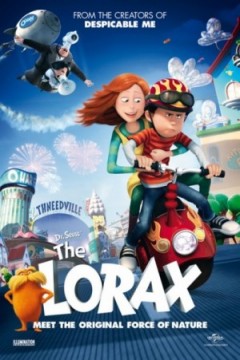

And yet, even so, the movie is stunning and beautiful in every way, with a message that taps into something important, something with economic and political relevance for us today. In fact, the movie improves on the book with the important addition of “Thneed-Ville,” a community of people who live in a completely artificial world lorded over by a mayor who also owns the monopoly on oxygen.

This complicates the relatively simple narrative of the book, which offers a story of a depleted environment that doesn’t actually make much sense. The original posits an entrepreneur who discovers that he can make a “Thneed” — a kind of all-purpose cloth — out of the tufts of the “Truffula Tree,” and that this product is highly marketable.

Now, in real life, any capitalist in this setting would know exactly what to do: immediately get to work planting and cultivating more Truffula trees. This is essential capital that makes the business possible and sustainable through time. You want more rather than less capital. An egg producer doesn’t kill his chickens; he breeds more. But in the book (and the movie), the capitalist does the opposite. He cuts down all the trees and, surprise, his business goes bust.

The book ends with the aging capitalist regretting his life and passing on the last Truffula seed to the next generation. The end. However, the movie introduces us to the town that is founded after this depletion occurs. It is shielded off from the poisoned and depleted world outside, and oxygen is pumped in by the mayor who holds the monopoly on air and builds Lenin-like statues to himself. The people eventually rise up when they discover that “air is free” and thereby overthrow the despot, chopping off the statue’s head.

It was this line about how air is free that clued me in to the movie’s possible subtext. You only need to add one metaphor to see how this movie can be the most important and relevant political-economic drama of the season.

The metaphorical substitution is this: The Trees are Ideas.

Now, the action really begins. You can even see that the dazzling tufts of the trees look like how we might imagine that an idea looks. It is puffy, colorful, silky, and has the scent of “butterfly milk.” And of course the tufts are the essential capital that makes the business possible. The Thneed from which the tufts/ideas are made is useful for anything from wearing as a hat to functioning as a hammock. It’s sheer flexibility adds to the allegorical flavor.

Of course the trees are renewable just like ideas. You can draw from them but you dare not forcibly prevent access to them, much less kill them. And yet every time the axe slices through the trunk, the ideas are rendered non-renewable. The axes represent the state’s laws that introduce artificial scarcity into the non-scarce realm of ideas. Do this enough — and private businesses use the government’s laws to do this all the time these days — and you kill what gave rise to the business in the first place.

And in this case, the cooperation of the capitalists makes total sense. When a business uses “intellectual property” law to forcibly monopolize an idea — Apple’s touch screen, big pharma’s medicine formulas, a tune recorded by an industry mogul, a story printed by a big publisher — it is killing that idea for others to learn from and use. The idea is made non-renewable for a period of time dictated by the government. This introduces a propensity toward economic stagnation and decline. It might seem to make sense in the short run but in the long run, everyone suffers.

This is exactly what we see in the real world. Industries that are not cutting down the trees of ideas are flourishing. Fashion is innovative and dynamic. The cooking world shares recipes and techniques. The open-source software movement is innovating every day. In contrast, industries where IP is dominant have a tendency toward monopolization and stagnation: pharmaceuticals, proprietary software, old-line publishers, for example. It is especially interesting to remember that one of the most controversial and hated monopolies of our time happens to be Monsanto’s patents on seeds.

In the movie, the results are put on display in the most compelling way. The town of Thneed-ville is stagnant. Nothing is growing, nothing is changing, nothing is truly alive. It is frozen and fixed, cartelized by a single mogul who provides everyone that essential thing: air. Tellingly, there is total unity between the owner of air and the state. It is the ultimate corporate state, and it has bamboozled everyone into thinking that this is just the way the world is supposed to work. They know of no better way.

This situation changes when a young boy discovers the truth about what happened to ideas. He finds out that they were once plentiful and provided all the life and energy that society needs to thrive and grow. He is given a single seed to a Truffula tree — and it represents the hope that the world of ideas could again come to exist and inspire the recreation of a thriving, dynamic, progressive, growing society.

So of course the mayor has to steal the seed that represents hope for ideas again. A massive chase ensues, and, in the course of it, the boy breaks down the wall between Thneedville and the darkness outside. It is enough for people to discover that air is not scarce but rather belongs to everyone. They begin to turn on the mayor and sing a great song and dance a dance in complete defiance.

As in real life, once the ruler has lost the confidence of his subjects, his rule is over. The seed is planted right in the middle of town, and the air monopoly is ended. Eventually the beauty and life of the world is restored.

There are wonderful lessons to this movie if rendered in this metaphorical way. Look at what we are doing to ourselves with the imposition and enforcement of the gigantic thicket of “intellectual property” that is taking over the world. It is like a huge thicket of thorns, and we can hardly move without getting stuck and stabbed. It is transforming the nature of the market, which needs ideas as we need oxygen, from a world of free exploration into one with billions of invisible cages. This is slowing down progress, killing creativity, monopolizing production in the hands of the rich and powerful, and even threatening the digital age itself.

The lesson is summed up in the incredibly inspiring anthem at the end:

We say let it grow

Let it grow

Let it grow

You can’t reap what you don’t sow

It’s just one tiny seed

But it’s all we really need

It’s time to banish all your greed

Imagine Thneedville flowered and treed

Let this be our solemn creed

We say let it grow