In this episode of the Libertarian Tradition podcast series, part of the Mises Institute’s online media library, Jeff Riggenbach discusses the life of Robert Anson Heinlein (1907–1988), author of The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress and many other wonderful novels and short stories, and addresses the question of whether Heinlein was a libertarian.

You can also read the transcript below:

When Robert Anson Heinlein died 22 years ago this month, in Carmel, California, at the age of 80, the wonder of it all was that he had managed to live as long as he did. Heinlein, who was born in 1907 in Butler, Missouri, a small town about 65 miles south of Kansas City, had been in poor health for most of his adult life.

His family had connections with the powerful Pendergast political machine, the outfit that later put Harry Truman in the US Senate, but Heinlein still had to spend his freshman year in a two-year Kansas City “junior college” — what today we would call a “community college” — before the Pendergast machine was finally able to wrangle him an appointment to Annapolis. After graduating from the naval academy in 1929 with a degree in mechanical engineering, Heinlein went to sea as an officer. But in his fourth year of active duty, he contracted tuberculosis and was honorably discharged — retired, really, with a small pension — after a lengthy hospitalization at Navy expense.

It was now 1934, the depths of the Great Depression. Robert A. Heinlein was 27 years old and living in Los Angeles, where the Navy had sent him upon his graduation from Annapolis five years before. He applied for admission to graduate school in physics and mathematics at UCLA, was accepted, and enrolled in classes there. But he dropped out after only a few weeks, partly for reasons of his still-precarious health, partly because he had become interested in politics and wanted to devote his time to working for Upton Sinclair’s gubernatorial campaign instead of studying math and physics.

Sinclair was an outspoken and self-identified socialist, whose campaign as the Democratic nominee for governor of California in 1934 was an outgrowth of his EPIC movement. “EPIC” was an acronym for End Poverty in California. In Sinclair’s words, the EPIC

movement propose[d] that our unemployed shall be put at productive labor, producing everything which they themselves consume and exchanging those goods among themselves by a method of barter, using warehouse receipts or labor certificates or whatever name you may choose to give to the paper employed. It asserts that the State must advance sufficient capital to give the unemployed access to good land and machinery, so that they may work and support themselves and thus take themselves off the backs of the taxpayers. The “EPIC” movement asserts that this will not hurt private industry, because the unemployed are no longer of any use to industry.

Robert A. Heinlein worked for Sinclair’s campaign in 1934 — it won a little more than a third of all the votes cast in the election — then stayed with the EPIC movement for a few more years. He became a staff writer for, then editor of, the EPIC News, the movement’s flagship publication, with a paid circulation of two million. Having discovered what seemed to be a natural bent for writing, he tried his hand at a novel — a utopian socialist polemic entitled For Us, the Living, that never saw publication until after his death. In 1938, he ran unsuccessfully for a seat in the California state legislature on an EPIC platform. Then, in 1939, at the age of 32, he began writing short stories for the commercial science fiction magazines.

“Isaac Asimov, who knew Heinlein from the mid-’30s on, was convinced that his personal political views were largely a function of the woman he was married to at the time.”

He enjoyed immediate success. Within months of publishing his first short story in the pages of the leading science fiction magazine of the day, Astounding Science Fiction, he was widely regarded as the leading writer in the field. Within eight years, by 1947, the year he turned 40, he had become the first science-fiction writer to break the pulp barrier — that is, the first science fiction writer to publish not just one story but an entire series of stories, not in the cheaply produced “pulp” magazines like Amazing Stories, Astounding Science Fiction, or Thrilling Wonder Stories, but rather in the more expensively produced, more prestigious, larger-circulation, better paying, “slick” magazines like Town & Country and the Saturday Evening Post. The Saturday Evening Post alone published nearly half the stories, including the title story, that made up Heinlein’s celebrated 1951 collection, The Green Hills of Earth.

It was also in the late ’40s that Heinlein began publishing science fiction stories in Boy’s Life, the monthly magazine of the Boy Scouts of America. It was in the late ’40s that he began writing, at the rate of one novel per year, what Brian Doherty calls “a series of S.F. novels for boys, published by Scribner’s, that seemed to make it into every high school and elementary school library” — a series of “coming-of-age adventure tales” that made Heinlein a top favorite author of baby boomers long before those boomers were old enough to vote or order a drink in a bar.

Meanwhile, he wrote science fiction for adults as well. During the ’50s and ’60s, Heinlein won four Hugo awards for best science fiction novel of the year. In 1969, he joined Walter Cronkite on national television to offer commentary on the first manned moon landing in history. In 1975, he was named the first recipient of the Grand Master Award for lifetime achievement in the field, by the Science Fiction Writers of America. By the time of his death in 1988, his nearly four dozen books — including novels and collections of short stories — had sold more than 40 million copies. And they haven’t stopped selling in the more than two decades that have gone by since then.

Why is all this important from the point of view of the libertarian tradition? Because, among the many hundreds of thousands of readers who made Robert A. Heinlein’s career in science fiction such a brilliant success were quite a few who later came to think of themselves as libertarians and to associate themselves, in one way or another, with the organized libertarian movement. Not a few of these would be happy to tell you that it was by reading Heinlein’s stories and novels that they discovered libertarian ideas and became persuaded of their power and truth.

In the early 1970s, according to a survey undertaken at the time by SIL, the Society for Individual Liberty, one libertarian activist in six had been led to libertarianism by reading the novels and short stories of Robert A. Heinlein. Among the prominent libertarians of the late 20th Century who have named Heinlein as an important influence on the development of their own political thinking were Dave Nolan (the founder of the Libertarian Party) and the late Samuel Edward Konkin III.

four most influential libertarian novels

of the last century.”

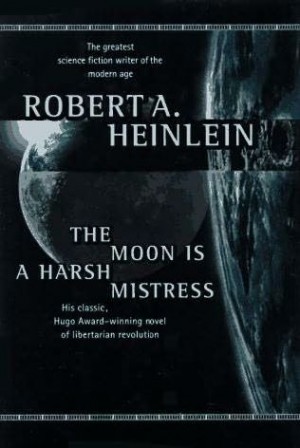

But was Heinlein a libertarian? There certainly are libertarian ideas in some of his books. The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress, for example, the winner of the Hugo award as the best science fiction novel of 1966, is the story of a libertarian revolution on the moon — a revolution designed to free Luna from the control of politicians and bureaucrats on Terra, that is, the Earth.

One of the leaders of the revolution is a “distinguished man with wavy white hair, dimples in cheeks, and [a] voice that smiled,” Professor Bernardo de la Paz, who speaks of “the most basic human right, the right to bargain in a free marketplace.” De la Paz calls himself “a rational anarchist” and argues that the question we need to put to ourselves when thinking about political issues is this one: “Under what circumstances is it moral for a group to do that which is not moral for a member of the group to do alone?” According to Professor de la Paz, this is “the key question … [a] radical question that strikes to the root of the whole dilemma of government.”

As the professor puts it,

A rational anarchist believes that concepts such as “state” and “society” and “government” have no existence save as physically exemplified in the acts of self-responsible individuals. He believes that it is impossible to shift blame, share blame, distribute blame … as blame, guilt, responsibility are matters taking place inside human beings singly and nowhere else.

Both in his physical appearance — the wavy white hair, the dimples, the smiling voice — and in his ideas, Professor Bernardo de la Paz bears a striking resemblance to a real-life libertarian who flourished and enjoyed considerable influence within the libertarian movement during the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s — Robert LeFevre. Now it so happens that Robert A. Heinlein and his third wife, Virginia Heinlein, lived in Colorado Springs throughout the 1950s and through the first half of the 1960s, the very period during which Robert LeFevre, a neighbor of theirs as it turns out, was serving as editorial page editor of the Colorado Springs Gazette-Telegraph.

Heinlein was writing The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress during the years when LeFevre was operating his famous Freedom School up the road a few miles in Larkspur and working to transform it into a degree-granting, four-year institution he wanted to call Rampart College — during the years when, in effect, LeFevre was transforming himself from an editorialist, controversialist, and rabble rouser to a professor. It has generally been assumed, though it was never confirmed by either Heinlein or his widow while they were alive, that the fictional Bernardo de la Paz was based on the real Robert LeFevre.

The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress is unquestionably a libertarian novel. It is unquestionably one of the three or four most influential libertarian novels of the last century. But whether its author, Robert A. Heinlein, can plausibly be described as a libertarian in his personal political views remains a troubled question.

We have seen that Heinlein’s first period of political activism, in the mid-to-late 1930s, was devoted to the advocacy of policies like a guaranteed annual income, universal tax-funded schooling, and government seizure of unused private factories and farms so they could be transformed, at taxpayer expense, into workers’ co-ops. Whatever this is, it is not libertarianism.

Heinlein’s next period of political activism came in the late 1950s, during the very years when he was first getting acquainted with Robert LeFevre. On April 5, 1958, the Colorado Springs Gazette-Telegraph published a full page ad sponsored by — but let’s let Robert A. Heinlein tell the story. The following quotations are taken from the full-page ad he wrote in reply and paid to have published a week later, on Saturday, April 12, 1958.

Last Saturday in this city appeared a full-page ad intended to scare us into demanding that the President stop our testing of nuclear weapons.

The instigators were seventy-odd local people and sixty-odd national names styling themselves “The National Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy.”

This manifesto … is the rankest sort of Communist propaganda … concealed in idealistic-sounding nonsense.

We the undersigned … read that insane manifesto of the so-called “Committee for a ‘Sane’ Nuclear Policy” and we despised it. So we are answering it ourselves — by our own free choice and spending only our own money.

If it comes to atomic war, the best we can hope for is tens of millions of American dead — perhaps more than half our population wiped out in the first few minutes.

The risks cannot be avoided other than by surrender; they can be reduced only by making the free world so strong that the evil pragmatists of Communism cannot afford to murder us. The price to us will be year after weary year of higher taxes, harder work, grim devotion … and perhaps, despite all this — death. But we shall die free!

We the undersigned are not a committee but simply two free citizens of these United States. We love life and we want peace … but not “peace at any price” — not the price of liberty!

Poltroons and pacifists will think otherwise.

Heinlein urged his readers to join a new organization he was starting up, called the Patrick Henry League, to promote his ideas.

Again, whatever this may be, it is not libertarianism. As Murray Rothbard explained in his classic essay “War, Peace, & the State,” published in 1963, five years after the publication of Heinlein’s fatuous polemic, suppose

Jones finds that he or his property is being invaded, aggressed against, by Smith. It is legitimate for Jones … to repel this invasion by defensive violence of his own. But now we come to a more knotty question: is it within the right of Jones to commit violence against innocent third parties as a corollary to his legitimate defense against Smith? To the libertarian, the answer must be clearly, no. Remember that the rule prohibiting violence against the persons or property of innocent men is absolute: it holds regardless of the subjective motives for the aggression. It is wrong and criminal to violate the property or person of another, even if one is a Robin Hood, or starving, or is doing it to save one’s relatives, or is defending oneself against a third man’s attack.

Now, with regard to nuclear weapons, here is what Rothbard had to say:

While the bow and arrow and even the rifle can be pinpointed, if the will be there, against actual criminals, modern nuclear weapons cannot.… These weapons are ipso facto engines of indiscriminate mass destruction. (The only exception would be the extremely rare case where a mass of people who were all criminals inhabited a vast geographical area.) We must, therefore, conclude that the use of nuclear or similar weapons, or the threat thereof, is a sin and a crime against humanity for which there can be no justification.

“Heinlein made it clear that he expected all Americans to cheerfully pay ‘higher taxes’ to implement the policy of mass murder he espoused.”

Since “it is precisely the characteristic of modern weapons that they cannot be used selectively, cannot be used in a libertarian manner,” Rothbard argued, “therefore, their very existence must be condemned, and nuclear disarmament becomes a good to be pursued for its own sake. And if we will indeed use our strategic intelligence, we will see that such disarmament is not only a good, but the highest political good that we can pursue in the modern world.”

Ten years later, in his invaluable introduction to the libertarian idea, For A New Liberty: The Libertarian Manifesto, Rothbard summed up his view of the point Robert A. Heinlein had made in that 1958 ad in the Colorado Springs Gazette-Telegraph.

Anyone who wishes is entitled to make the personal decision of “better dead than Red” or “give me liberty or give me death.” What he is not entitled to do is to make these decisions for others, as the prowar policy of conservatism would do. What conservatives are really saying is: “Better them dead than Red,” and “give me liberty or give them death” — which are the battle cries not of noble heroes but of mass murderers.

It is noteworthy, is it not, that while Heinlein boasted that he and his wife had paid for the publication of their ad by “spending only our own money,” he simultaneously made it clear that he expected all Americans to cheerfully pay “higher taxes” to implement the policy of mass murder he espoused. Similarly, the man who wrote stories depicting a successful space program funded by private enterprise also made it clear that he expected Americans to pay taxes — that is, to tolerate government theft of their money — to support NASA.

Isaac Asimov, who knew Heinlein from the mid-’30s on, was convinced that his personal political views were largely a function of the woman he was married to at the time. In the ’30s, when he was married to wife #2, Leslyn MacDonald, whom Asimov describes as “a flaming liberal,” Heinlein was working with Upton Sinclair and his EPIC movement. Twenty years later, married to wife #3, Virginia Gerstenfeld, he re-emerged as a Cold Warrior fixated on the supposed nobility of the military and newly devoted to a “free market” for which he had had little use during the years of the Great Depression.

If so it was, I say, “so be it.” Many men have tailored their beliefs to match those of their wives. They have found that it helps to preserve and promote domestic harmony. And they believe that domestic harmony is a valuable thing, a thing worth preserving. Robert A. Heinlein was hardly the only man, or even the first man, to venture down this path.

What we need to stay focused on here, I think, is that in his books, Heinlein was his own man. He found social and political ideas — ideas about the different ways human beings might figure out to live together peaceably in large groups — endlessly fascinating. He liked to fool around with such ideas, speculate about how they might work out in practice. Libertarian ideas weren’t the only ones he fooled around with and speculated about in his fiction. But because of his interaction with Robert LeFevre in Colorado in the ’50s and ’60s, libertarian ideas were among those he toyed with and dramatized in certain of his stories. Whether he was personally a libertarian or not, all those of us who are libertarians owe him a profound debt for writing The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress. For that book alone, Robert A. Heinlein has earned a place in the libertarian tradition.

[This article was first published online as a Mises Daily article and is transcribed from the Libertarian Tradition podcast episode “Robert Anson Heinlein (1907–1988).”]