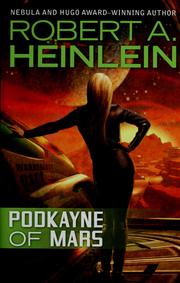

When Robert Heinlein told a tale, it was with a compelling and engrossing voice. He created personalities with interest and depth and fashioned dramatic interactions to keep us involved. However much or little happens to his characters, the experience for us readers is enhanced because we become invested in the people who inhabit his stories. Even a book like Podkayne of Mars, which one might quibble is a touch underplotted, is a satisfying read because of the investment in the people.

When Robert Heinlein told a tale, it was with a compelling and engrossing voice. He created personalities with interest and depth and fashioned dramatic interactions to keep us involved. However much or little happens to his characters, the experience for us readers is enhanced because we become invested in the people who inhabit his stories. Even a book like Podkayne of Mars, which one might quibble is a touch underplotted, is a satisfying read because of the investment in the people.

Podkayne Fries, a girl on the verge of womanhood with dreams of becoming an interplanetary ship captain, is the principle narrator and protagonist of the story. She and her younger brother Clark get an opportunity to accompany their uncle on a voyage to Venus and Earth. Her uncle, however, is an ambassador and there are those who would interfere with his mission, disdaining no despicable act in their attempts. That is about all there is to the story structure. There are a few plot points thrown in – such as the mysterious object Clark smuggles on board, or the solar storm that catches them between planets – and the ending is harrowing, but it becomes clear early on that the novel’s strongest points lie elsewhere.

Consider the voice of the narrator, which comes to us from the journal of Podkayne Fries. In describing the moments before embarking, she says,

I got kissed enough times to start a fair-sized epidemic if any one of them had had anything, which apparently they didn’t. I got kissed by boys who had never even tried to, in the past – and I assure you it is not utterly impossible to kiss me, if the project is approached with confidence and finesse…

That represents a typical passage in Podkayne of Mars; rather than opt for a plain transmission of information, Heinlein injects life into his prose. She does not get kissed a lot; she gets kissed enough to start an epidemic. He does the same with his characters, and there are many colorful ones here. Chief among these is Podkayne’s little brother Clark, two parts profiteer and Objectivist fellow traveler and one part conniver. Of him, Podkayne says,

Clark is, however, a very satisfactory person to fume with, because, if he isn’t busy, he is always willing to help a person hate anything that needs hating; he can even dig up reasons why a situation is more vilely unfair than you thought it was.

Also,

… Clark just looked bored and contemptuous and said nothing, because Clark would not bother to interfere with Armageddon unless there was ten percent in it for him.

The characters and the details of their voyage take up perhaps the largest chunk of the novel. Next up is Venus, their first port of call and a land of interest for the socio-philosophical reader.

There is much discussion in libertarian circles about just what Heinlein’s political philosophy was. While in his early days he was some form of leftist, socialist progressive, his views underwent a pronounced change later on (and he earned himself a divorce in the process). Many are tempted to call him a libertarian based on The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, perhaps his most famous work, and these same folks will find similar evidence in Podkayne of Mars. Venus is owned by a single corporation and everyone who lives there is either a tenant, an employee or a guest (tourist). Just about anything goes on Venus, especially gambling, as long as the money keeps rolling in. Murray Rothbard might be tempted to point out that a single corporation dominating the economy would be as blind as any government, but Heinlein is a touch stingy on details; his main intent seems to be an exploration of how the profit motive keeps violence to a minimum. Indeed, even kidnappings on Venus are handled with the same lack of animosity as trade negotiations, and with only a little more distrust.

My own view is that Heinlein may have turned to a more conservative economic ideal, while preserving his hatred of racism, and that this gave a libertarian sheen to his outlook, but he never progressed beyond what Lew Rockwell would call a Regime Libertarian. However much he recognized the necessity of markets, however much he might be inclined to indulge choice in certain matters, however much he argued for equality of rights, Heinlein, it seems to me, was always a supporter of the Establishment. One need not turn to Starship Troopers for evidence; passages of the present work can be cited.

Podkayne’s Uncle Tom makes a very revealing speech about politics. “Politics,” he says, “is the human race’s most magnificent achievement. When politics is good, it’s wonderful… and when politics is bad – well, it’s still pretty good… Politics is just a name for how we get things done… without fighting.”

There is in the text, to my mind, every indication that Heinlein meant what he made Uncle Tom say. It reminds me of a recent appearance by P.J. O’Rourke on John Stossel’s show in which they talked about politics and what it means to be a libertarian. After a few necessary jokes at politicians’ expense, P.J. got serious and informed us that we the voters were the real problem, not the politicians. Ultimately, we are meant to believe, the State is to be admired.

Whatever Heinlein’s true philosophy was, he seemed willing to explore libertarianism and to treat it fairly. Though The Moon is a Harsh Mistress is his most famous libertarian work, his explorations on that theme appear elsewhere too. Podkayne of Mars holds a good deal for the libertarian to consider, and while the story is not fantastic, it is solid enough, especially when combined with that Heinlein prose and voice.