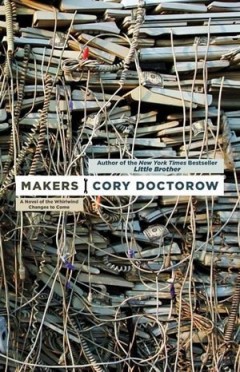

I didn’t like Makers. I wanted to like it. Cory Doctorow, the author, is a cool geek and something of an ally in the struggle against intellectual property, i.e., government grants of monopoly privilege. But overall I just did not enjoy the book for a number of reasons.

To be sure, there are things to like about Makers. If you’re an avid reader of Boing Boing, you might like it. I only dip my toes in occasionally. Reading Makers is a lot like reading Boing Boing in novel form. Cory excels at imagining interesting gadgets and cool new uses for current and upcoming technology — the kind of geeky tech and pop culture things he and his fellow bloggers share on Boing Boing all the time, only some unspecified number of years into the near near future. The book will probably date quickly, but this aspect of it was fun…for a while. When it comes to things, Cory has an expansive imagination and a deep understanding. When it comes to people and plotting, on the other hand, his imagination and understanding seem to me to be more limited.

Makers started out as a novella titled Themepunks, serialized on Salon.com, though it appears Cory envisioned it from the beginning as merely the first part of a novel. I wish he hadn’t. Makers consists of three parts and an epilogue, with Themepunks being part one, the first 100 or so pages. Like Luke Burrage, I enjoyed part one, for the most part, but thought the novel went downhill from there.

As the novel opens we are introduced to the first main viewpoint character, a tech reporter by the name of Suzanne Church (Andrea Fleeks in Themepunks1). Suzanne attends a press conference held by the new CEO of Kodak/Duracell (or Kodacell), Landon Kettlewell. Kodak and Duracell are struggling companies in the near future. There’s no longer a need or market for their products. I guess they failed to innovate and remain competitive in a changing technological landscape. Kodak I can see. But Duracell? People won’t need batteries in the future? Duracell will fail to develop new power cells for new products? Really? In any case, Kettlewell and his financial backers decide to buy and merge Kodak and Duracell and then essentially gut them. The idea is apparently to trade on the old companies’ good brand names and use their capital to back a creative new business model.

Under Kettlewell, Kodacell becomes a kind of Grameen Bank of venture capital, engaging in micro-financing of garage-next-door would-be inventors and entrepreneurs. The business plan is for Kodacell to find untapped creative geniuses throughout the country, provide them with funding and a business manager, and act as the central coordinator in a distributed network of small, independent teams. A pretty nifty idea. This relatively non-hierarchical business model, the focus on 3-D printers, and a number of other aspects of the novel will be appealing to many left-libertarians, I think.

Suzanne then takes on the role of embedded journalist and later blogger when she travels to Florida to follow Kettlewell’s star makers, two young guys named Perry and Lester. She befriends them and reports on what they’re doing and on their relationship with a resourceful local squatter community (another thing left-libertarians and off-the-grid survivalists will probably like). Thanks in large part to her reporting a new worldwide movement is spawned and later dubbed the New Work (too New Deal-esque, for my taste, but at least it was a voluntary private initiative). Kodacell quickly attracts imitators and the new venture micro-capital market is soon unsustainably flooded with an excess of money, credit, and competitors. Irrational exuberance, I suppose.

This is Cory’s explanation for the creation and bursting of the New Work bubble. Individual teams were profitable and raking in record returns on investment (ROIs), but their profits were measured in the tens and hundreds of thousands, not millions and billions. Supposedly, Wall Street didn’t know how to value venture micro-capital firms like Kodacell and lost confidence. It didn’t help that Kettlewell’s business plan involved finding 10,000 teams but only 1,000 teams had been found — due to competition and, I suppose, the lack of talent or difficulty finding it. All the venture micro-capital firms like Kodacell found themselves sitting on piles of idling cash.

I didn’t expect Cory’s explanation of the Dotcom and New Work booms and busts to highlight the government’s role in driving the business cycle, à la the Austrian Business Cycle Theory (ABCT), and I was not disappointed. A minor PhD-candidate character thinks FDR spent the US out of the Great Depression, and I think it is safe to assume Cory shares this view. Many people do. Left-libertarian Kevin Carson enjoyed the New Work boom and bust of part one to such an extent that his review focuses almost entirely on it and likely colored his evaluation of the rest of the novel.

At any rate, part one ends with Suzanne heading off to greener pastures, to follow the cutting-edge Russian medical clinics spawning a new global weight-loss movement (the fatkins diet), and the collapse of the New Work. Part two picks up years later and introduces a whole raft of new characters who will feature prominently throughout much of the rest of the book: Kettlewell’s wife and kids, Tjan’s kids (Tjan being the original business manager Kettlewell sent to Perry and Lester), a ride activist named Hilda, a cutthroat Disney executive nicknamed Sammy, a sweet goth kid — well, young man — who goes by the name of Death Waits (trying too hard?). Lester and Perry have moved on to set up an ever-evolving amusement ride in an abandoned Walmart using 3-D printers and maintenance robots, a sort of museum dedicated to the heyday of the New Work.

Parts two and three of the book are all about the increasing popularity of the ride, its spread around the country and then the world, and the clash of the ride fanbois with a Disney World in decline. The focus is no longer really on makers per se. The Disney exec, Sammy, manages Disney’s currently most succesful attraction, a Fantasyland he re-themed into a nostalgic goth amusement park. Death Waits is his top assistant.

Sammy at first engages in what he calls competitive intelligence, spying on Lester and Perry by pretending to be a regular customer in order to see what the competition is up to. But he grows alarmed at the increasing popularity of the ride and then resorts to outright sabotage and eventually brings intellectual property lawsuits down on our protagonists’ heads. As the book progresses, Sammy appears to be shaping up to be the primary villain of the novel.

As I mentioned earlier, where Cory shines is in coming up with and describing gadgets and new advancements in technology. He also likes to a drop a lot of pop culture references, though personally I got the feeling like he was trying a bit too hard at times. Perhaps the most clever and useful invention by Perry and Lester was to take standard RFID tags (or arphids) and repurpose them so that they could be used with your computer to catalog and tag the location of any object you own. No more needing to remember where you put your remote or your tools or a particular book. Just enter search terms on your computer, like doing a google search, select what you’re looking for and the RFID tag on the item will start glowing.

That’s actually the kind of thing the New Work consisted of, taking existing technologies and combining and repurposing them in clever ways. Remixing. The kind of thing intellectual property is designed to prevent. But one of my complaints about Makers is that a lot of the stuff the New Work people such as Lester and Perry liked to make tended to be kitschy novelty-type items like Perry’s seashell robot toaster.

At the risk of sounding like a socialist or tarnishing my Austrian econ and geek cred, it often seemed to me like these guys were wasting their considerable talents. I mean, couldn’t Lester find anything better to do than build ever larger and more sophisticated mechanical, yes mechanical, calculators out of scavenged junk (at first a few car doors with parts made of laser-cut and welded soda cans, later taking up an entire building) whose sole purpose were to pump out varying amounts of his favorite brown M&Ms depending upon number and type of physical objects inserted into them (G.I. Joe heads, footballs, etc.)?

Cory’s writing — characterization, prose, and plotting — is generally competent, not excellent, but oftentimes clumsy. The characterization is weak. There is little differentiation between characters in their behavior and dialogue. Most of the characters, regardless of age, act like immature adolescents from time to time when needed to further the plot, not always because it makes sense for the character. The adolescent excess even comes out in the way most of the characters eat most of the time, wolfing and gobbling down nuclear-hot burritos and whatnot. I’m making allowances for the 10,000 calorie per day fatkins diets in this assessment, by the way. And they’re not merely startled or amazed, they’re boggled. Cory loves the word ‘boggle’. Not a lot of subtlety. I suspect this sort of characterization will work better in Cory’s YA novels, but it just doesn’t feel right here.

At times we’ll see a new side of a character’s personality suddenly, such as Sammy’s “wolfishness” (with a name like Sammy?) to intimidate his fellow Disney execs, with little or nothing before or after to suggest such traits. Other things happen right out of the blue just to further the plot as well, such as the inexplicable decision of Perry and Hilda to suddenly visit the beach in Florida. Not bothering to check the weather — in the mobile internet age, for goodness sake, why? — they run right smack into a hurricane that travels inland and trashes the ride while they’re away, further cementing Lester’s impression that Perry is neglecting the ride in favor of chasing tail and being a douchebag activist. As Luke Burrage points out in his audio review podcast, this incident is one particularly egregious example of the protagonists lurching from crisis to crisis, which they seem to solve rather handily and quickly, while an overarching plotline seems to be lacking. Where is it all headed?

The pacing of the book is uneven as Cory frequently interrupts the action to have his characters explain this or that pop culture reference or gadget or technological process. It can get rather tedious and is sometimes handled clumsily. Several times at least, I noticed, like Luke Burrage, something being explained more than once, such as the fact that the people who work at Disney are not employees, they’re castmembers. Cory reuses some plot elements (private planes) and character descriptions as well. His fiction can get rather jargon-heavy; for example, in the first scene Kettlewell begins his explanation of Kodacell’s new business plan with “We will brute-force the problem-space of capitalism in the twenty-first century.” And some things that do not need to be described in detail are done so in tedious detail, including a lone and very graphic sex scene (and I’m no prude). Though don’t get me wrong…Cory is generally very good at explaining things clearly.

For many people there will simply be too many long educational lectures in the novel for it to be enjoyable. Often the long speeches are unnecessary, included purely to educate the reader rather than the other characters. One gets the impression the purpose of Makers is to educate as much as entertain, but often the educational aspect interferes with the entertainment aspect.

One particularly clumsy passage that was completely unnecessary occurs near the middle of the book. It’s also an example of bad characterization transparently used as a plot device. Suzanne and Kettlewell travel to Florida with Kettlewell’s family for a reunion with Lester and Perry. They thought and searched long and hard for the perfect gifts for two guys who can make just about anything. They give the guys old, broken-in, but still in good condition, leather baseball gloves. You just can’t make something like that in a workshop with a 3-D printer. Expensive collectors items for baseball enthusiasts, I’m sure, but for mechanically-inclined computer geeks? I just don’t see it. Nothing we’re told about Perry and Lester up to this point or even afterward gave me any reason to believe they were into baseball and would appreciate such a gift. I know I wouldn’t.

But to make matters worse, Cory has Suzanne and Kettlewell explain the significance of the gifts to them! For nearly two pages! As if they wouldn’t realize it instantly on their own. Instead of having the gift-givers bloviate ad nauseum, it would have made more sense to explain the significance to the reader much more briefly via internal musing by Lester and/or Perry. At most, only a sentence or two by Suzanne or Kettlewell would have been necessary.

I was also put off at times by Cory’s general and socio-economic worldview — partly sense of life, I suspect, and partly Cory’s consciously-held political views. To my knowledge, from his non-fiction writings, Cory is something of a progressive social democrat, good on civil liberties and war but bad on most everything else. Some examples from part one alone, the better part of the book:

Lester doesn’t blame himself at all for his morbid obesity. No, it’s all the fault of bad genetics and restaurants; the universe has it out for him. It has nothing to do with lack of willpower, poor choices, bad eating habits, or the like.

Perry rails against planned obsolescence. Apple intentionally built the first iPods with inferior materials so that they would wear out in a year and you’d want to replace yours with the newer, more advanced model. Surely people wouldn’t want the newer, better models otherwise. Considerations such as cost of production, meeting an attractive price point for consumers, and an untried product couldn’t have anything to do with not going with the state-of-the-art.

Lester and Perry rail against sweatshops. Lester explains to Susanne: “There’s no way it’s cheaper to make a million solders by hand than by robot unless your labor force is locked in, force-fed amphetamine, and destroyed for anything except prostitution inside of five years.” Cheaper to use robots? Really? Always? I find that hard to believe. Robots aren’t cheap. And locked in how, exactly? I didn’t know that sweatshop workers generally are physically forced by corporations to take drugs and work. As for being destroyed for anything except for prostitution, often a “sweatshop” job is the most appealing, highest-paying job available in developing countries, a better alternative to prostitution and the like.

Late in the book, Suzanne remarks to Sammy that Disney’s Carousel of Progress is “like an American robot performance of Triumph of the Will.” WTF!?! Did Cory just analogize a private themepark attraction depicting the impact of market-driven technological progress on a “typical” American family to a Nazi propaganda film? Yes, he did. Even if Suzanne’s only point was that they are both propaganda pieces, that’s just so mindbogglingly (HT Cory) wrong.

Maybe it’s unfair to ascribe the views of Cory’s characters to him. I’m aware of the danger in doing so. It may be true of most authors that one should be wary of doing this. But Cory’s fiction has an unmistakable educational aspect, remember. And these views I’m criticizing are expressed, largely unopposed, by the same sympathetic characters who express other views that are well-known hobby-horses of Cory’s, such as opposition to intellectual property. It all forms a fairly consistent worldview that fits with what I know about Cory’s own worldview from his non-fiction work. Luke Burrage also got the impression that Cory makes little effort to mask his authorial voice.

But, as I said, Cory is good on some things. He’s got a decent grasp of business and economics at a superficial level. He understands the role of competition, innovation, emulation, supply and demand on the surface, but he lacks a deeper understanding of the underlying fundamentals. As is usually the case, he’s good on civil liberties and intellectual property here. Cops and the TSA are frequently mocked and portrayed in a bad light. His protagonists extol the virtues of open source and fight against intellectual property enforcement, while his villains “compete” with sabotage and intellectual property lawsuits. He shows the harm that IP causes and extols the benefits of competition, innovation, emulation, openness, and rapid change.

I was even surprised by a few instances in which Cory illustrates the ill-effects of some social welfare programs. In part one, Suzanne mentions in a blogpost that a government housing project was an urban-renewal nightmare filled with crime and junkies, “low-rent” high rises too expensive for the shantytowners. Early in part two, a minor character mentions to Suzanne that a lot of doctors are moving to the Russian clinics from Sweden and Denmark to get out from under their socialist medical systems.

A few other tidbits of interest to libertarians: Russia is described as a place where there are lots of rules but nobody follows them. The shantytown, with a “mayor” whose authority rests on respect, has interesting contractual property arrangements without a formal legal system. Perry observes that good people do shitty things one tiny rotten compromise at a time, by being “reasonable.” Perry and Lester refuse to play the statist-corporatist game, and enforce their intellectual “property.” And Perry points out that improving technology is helping the world get better by making it cheaper and easier to make and do things; we’re getting better at routing around the bullies.

One interesting idea that Cory introduces late in the novel takes a page from the patent troll playbook to attack IP. Kettlewell innovates the idea of venture-capital-funded litigation against big, old corporations (“monopolists”) that abuse the IP legal system. This aspect is a bit muddled, however. Though Cory recognizes that big, old corporations often write government legislation for politicians to benefit themselves at the expense of smaller, upstart competitors, one gets the impression it is more a matter of evil corporations corrupting benign government. This anti-IP litigation is presented as necessary to keep markets unstable (a good thing) and competitive and to free up the capital of those nasty corporations, but one does not get the impression Cory understands that it is through the state that people stabilize the market, make it uncompetitive, and maintain the status quo to keep capital locked up where it is. An unfettered market will redistribute capital from uncompetitive firms. The state is the primary problem; it is not the solution.

BEGIN MAJOR SPOILER SECTION

The ending of part three is stupid and petty. The Disney exec, Sammy, who is built up through parts two and three, the bulk of the novel, to be the main villain, turns out not to be. Instead, Perry, Lester, and the gang team up with him get revenge on what appeared to be a minor villain who had been hounding them from scene one. Rat-toothed Freddie, as Suzanne dubbed him, is a journalist whose affections she spurned in the beginning of the novel. From then on, he made it his career to trash her, Kettlewell, Perry, and Lester at every opportunity. He is essentially nothing more than an internet troll with a journalist’s platform, and Suzanne even describes him as such at least once. Don’t feed the trolls, she reminds her friends repeatedly, as the traditional advice goes. But was this the point of Makers? To pwn a troll? Really? That seems rather petty, however personally satisfying to the trolled.

Luke Burrage pointed out another odd thing about this event in his review, which he perhaps noticed because he previously read Little Brother and so picked up on a common element. In Makers, as in Little Brother, Cory, a blogger and champion of the new media, resorts to the old media to save the day. In Little Brother, it is a print journalist. In Makers, though much is made of the slow death of print journalism and though television news receives little or no mention, it is a television news show our protagonists use to take down an unsuspecting Freddie whom they’ve set up for a career-ending embarrassment by feeding him false information. It just seems an odd choice for Cory. I can kind of get it with respect to Little Brother, which is set closer to the present day and has teenagers rebelling against the Department of Homeland Security as its protagonists; print journalism is still respectable and children are not taken seriously. But in Makers, to ruin an online tech reporter, it just doesn’t make any sense.

From stupid and petty, we move on to an epilogue that is just depressing. It takes place years after the end of part three. Lester is dying of complications from his fatkins lifestyle. He’s basically burned out his body. His and Perry’s lives are largely wasted failures. The New Work was a bust. I guess it had some impact, but little of significance really seems to have changed in the world. We don’t even get to see the impact of the self-replicating 3-D printers Lester cooks up. I mean, the invention of self-replicating machines is a huge deal. Huge. Perry’s activist girlfriend, Hilda, who brought out the activist douchebag in him, changing the course of his life, has long since dumped his ass. He’s a lonely drifter taking odd jobs as he moves from place to place. Lester went to work for The Man, Disney World, contractually unfireable and given a huge budget, salary, and benefits package. But he’s a type of inventor that large, bureaucratic Disney really has no use for, so he whiles away his last days working on his mechanical calculator with a big Disney budget, not liking his job but unable to quit because his medical bills would quickly bankrupt him without his Disney medical insurance.

Is Cory illustrating the perils of two extremes here? The ideological activist and the sellout both fade into obscurity, have little lasting impact (that we are shown), and are kind of pathetic. Or is it just that Lester and Perry belong together and can only succeed and be happy making things together? Cory tries to salvage the depressing epilogue by having Perry stick around to make things again with Lester in his final days, which will be few because Lester quits his job at Disney, losing his medical insurance, in order to start a new business with Perry. Doesn’t quite cut it, I’m afraid. Is this what I read 400+ pages for? This and pwning a troll? Ugh.

END SPOILER SECTION

So I can’t recommend Makers, except perhaps for part one. You can read Themepunks serialized on Salon.com. If you want to give more than just part one a try before buying, the entire novel is serialized on Tor.com and, since Cory is a copyfighter, he has released the entire novel in a variety of digital formats for free on his website under a Creative Commons license (albeit a non-commercial one; FAIL). But do listen to Luke Burrage’s review of Makers. It’s hilarious.

I’m almost finished reading his YA novel Little Brother and will have a review of it up before long. I do like this one and recommend it. Keep an eye out for the review! I promise it will be shorter than this one.

I’m not sure what else might have changed from novella to novel other than this character’s name. ↩