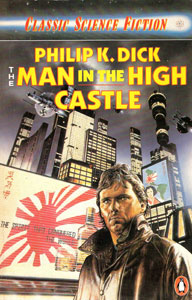

It seems to me that of the two most important elements of a story, plot and character, plot seems to be more masculine and character more feminine. That is to say, a story for men, if it skimps on either of the two, is more likely to skimp on character, while a story for women will shortchange the plot. The best stories, of course, are strong in both categories. Science fiction, being a more masculine genre — in fact the only genre of fiction whose readership is more male than female — has traditionally been solid on plot and hit or miss with the characters. There are exceptions, as one would expect, and Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, a Hugo Award winner, is one of these.

The story takes place in what was the present day when the novel was written, 1962, but in an alternate timeline where Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan won World War II. The United States has been carved into puppet governments; Germany has sent astronauts to Mars, drained the Mediterranean for farmland and committed multiple genocides; Japan controls the west coast of North America, having become a cultural as well as political hegemon.

It is a marvelous setting, both in conception and in description. Dick’s prose makes it come alive with a few deft touches here and there, sparse but effective. Whereas in most stories the setting serves as a place for the plot to take place, the reader here gets the sense that the plot is just something to have happen in the setting. The world and its characters are the point; what they do in the narrative has less importance.

This narrative, such as it is, consists of several storylines in the Pacific States of America and the Rocky Mountain States. Each storyline has a principle character connected in some way, often unbeknownst to him or her, with the others. The connections are frequently tenuous and the separate stories never get around to merging with, affecting, and reinforcing one another in a satisfying manner, but as separate, open-ended short stories they do work well. Dick has a knack for creating a compelling scene — composing with a patience, rhythm, sensitivity, and attention to detail one finds lacking in many story-driven works — and for putting interesting characters into them. Though in the big picture the story structure does not please as much as it might have, the various scenes along the way are of good quality, some of them superb.

One that sticks out is a scene in which an antique shop owner, Robert Childan, has dinner at the house of a Japanese couple. The Japanese are a race that Childan views with disdain and admires, often simultaneously, and Dick takes us into Childan’s thoughts during the dinner as he moves from almost obsequious admiration to smug superiority. It all occurs in his head, set off by small cues and bits of conversation while the Japanese couple are merely having dinner, unaware of the turbulence in the thoughts and sentiments of their guest. It is perhaps the scene most emblematic of Dick’s novel: almost everything of significance is about Childan’s character and happens in his head. The physical action is almost entirely trivial.

The different tales in the novel range from the less consequential one of Frank Frink, who is merely trying to make it through life as a Jew in hiding, to the vital one of Mr. Baynes, who travels to meet with a key official in the Japanese government to warn him about a German plot. Then there is the story of Juliana Frink, ex-wife of Frank, whose story is less consequential in the grand scheme of things but which is probably the most significant one for the novel itself.

SPOILERS SPOILERS SPOILERS

There are two books that figure prominently in the novel. One is The Grasshopper Lies Heavy, an alternate history novel within this alternate history novel in which the Allies win World War II. The book has been outlawed in all German-influenced territories but is nevertheless widely popular. The other is the I Ching, ubiquitous in the Pacific States (and as if to prove my point about plot, the author used it to guide the tale, even reportedly expressing dissatisfaction at where it led him but staying faithful to what it told him). Unlike the separate threads of storyline, these two books do come together at the end to put the finishing touches on the recurring theme of perception, illusion, and reality.

END OF SPOILERS

The Man in the High Castle is not a long novel, and it feels like Part I of a larger, more epic work. Philip K. Dick himself intended to write a sequel to it, and indeed a couple of his later novels were conceived as sequels but did not turn out that way. The world Dick creates could certainly support a grander tale, and when it is finished one feels like there are many exciting things to come, if only Dick had written them. With another four hundred pages or so we might have been treated to an exhilarating mix of storylines, but then again, if the I Ching really was guiding the plot, we might have wound up nowhere at all.

The characters consulting the I Ching are reflections of the author. It will surprise no libertarian to discover that this mystical author dealing with themes like the nature and reliability of reality would have some sort of basic leftist view. When he reads that FDR was assassinated, and that this was what prevented the US from getting out of the Great Depression and that for this reason the United States did not have the economic might to defeat Germany and Japan, he is likely to set the book down until he is done guffawing.

Nevertheless, the book is a good one, better than most sci-fi novels I have read. The setting, the characters, the individual scenes — all of these contribute to the reader’s enjoyment. If the book seems underplotted, almost like it was headed in a definite direction but got aborted before it was fully formed, this gives the reader only a mild disappointment to be mixed with all the good feelings the story evoked. Perhaps if Dick had done something sensible like fashion the plot himself, a better story would have resulted. As it is, I’m inclined to forgiveness based on the other merits; the flaws I shall blame on the I Ching.

Comments on this entry are closed.

Gideon Marcus November 6, 2017 @ 7:21 pm | Link

I did not know that PKD, himself, used the I Ching to write the book… only that Abendsen used it when composing Grasshopper.

Wheels within wheels.

Anyway, it’s a good book, but not a great one.

http://galacticjourney.org/november-6-1962-the-road-not-taken-philip-k-dicks-the-man-in-the-high-castle/