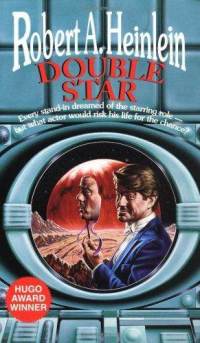

Robert Heinlein’s first Hugo Award winner was Double Star, a work that garners him far less attention today than his other Hugo winners. A reading of the novel will make obvious the reason for this: it is simply not as good. This is not to say that the book is poor, but for it to have won the Hugo Award in 1956, one must suppose either that it was a weak year for science fiction or that giving it the award was a mistake, akin to giving the Oscar to American Beauty or Shakespeare in Love.

It is something of a mystery to me why the novel does not amount to much. The protagonist has a distinct and interesting personality and the idea for the story holds promise. The prose is spare but efficient as you would expect from a Heinlein piece. What went wrong is that the plot is underdeveloped, a fault that would seem to be easily avoided, especially with a veteran author if he cares enough to put the effort into it. A writer needs to squeeze out of a story idea its potential, like one wrings the juice from an orange, and this is not achieved in Double Star. Given that The Puppet Masters came out a few years earlier, its weakness cannot be explained by an author who had yet to come into his own as a storyteller.

The main character is Lorenzo Smythe, an actor in the middle of some lean times but who preserves his pride and thespian affectation, though not to the point of becoming a caricature. He is offered a top secret job to impersonate a kidnapped Martian politician, Joseph Bonforte, until the man can be recovered. At stake is the peaceful equilibrium of human society.

The reader is no doubt interested by now. This is understandable. If he is familiar with Heinlein and his writing but has not yet read Double Star, he may even have the Amazon page opened in another window, one click away from making a purchase. I will not attempt to dissuade him, because it is not as if the book were unreadable, but if he could dally just a moment to learn more he can make an informed purchase.

The great disappointment that follows the great expectation is how little happens in the story. There are really only three episodes to speak of, with a little time in between for Lorenzo to review the tapes and writings of Joseph Bonforte and to practice imitating him in front of a small group who know the man and are in on the ruse. The three episodes themselves consist of very little, merely speechmaking and handshaking. A couple of times suspicions are raised, but there is little in the way of true danger, or counterplots and double-crosses, and only a few obstacles are placed in the path between the characters and their goals. In short, there is very little complexity.

Even if we pardon the simplicity of the plot as being due to its brevity, and even if we pardon the brevity, the episodes themselves lack tension. There is no acknowledgement of how complex and vast is the realm of politics, of how many actors there are who, lying in wait for several chapters, may spring onto the scene with their own motivations and thus cause grief for — or even come to the rescue of — the protagonist and in so doing send the story off in a new, unexpected direction. When we make our own plans, we do so in ignorance of what else is going on out there, and consequently our plans, more often than not, must be adapted and improved on the fly. Smythe’s plans, or rather those plans made for him, run into few difficulties and turn out pretty much as conceived. The few surprises lying in wait do next to nothing to interrupt.

It strikes me that this is a very Austrian insight. Perhaps Heinlein was suffering from a form of the fatal conceit applied to storytelling. This is not to say that any author ever could capture the immense complexity of reality, but he certainly can make it seem as if his characters are living in a world of intricacy beyond their understanding. The story could do with an acknowledgement of this. It could also use an injection of surprise and danger; it needs mystery and it needs obstacles; it could use a character or two whose goals are not what they seem. This would require reconceiving the plot, thinking more and delving deeper into possibilities, into what else and who else are out there. And if this means shooting past page 243 and writing on until page 500, then cut down another tree and make some pages!

Apart from being a bland but not terrible story with a protagonist whose engaging personality is almost wasted in it, the book solidifies my conception of Robert Heinlein and his political opinions. There is a lot more evidence here of a man who hated racism, was mildly disposed towards a market economy, and believed in limiting government intervention, but there is also an admiration of the system. Politics is ultimately noble, even if it is usually dirty, and a marvelous thing given the alternatives. The State, we are led to believe, benefits us though we have to keep an eye on it. In short, Heinlein never reached that understanding that the State does not preserve the market, it inhibits it; does not promote freedom but rather by definition curtails it; is not the friend of mankind but rather a tool for slavery.

Heinlein did far better than Double Star. With the exception of Orphans of the Sky I have never seen him do worse. Still, the book is not entirely without its merits, nor is it an uninterrupted exercise in tedium from the first to the last page. The reader could do worse than make that final click and order it; just do not go in with your expectations too high.