Before I studied Austrian Economics and profited from the clarity it brings to phenomena that otherwise seem chaotic and unfathomable, I read an article by Dave Barry that made me laugh. In it, he parodied the stock market, saying something to the effect of, “The DOW Jones plunged today when scientists discovered that Saturn had seven moons, and not six as previously thought.” That sentence encapsulated the mystifying and capricious vicissitudes of an economy I did not understand, much like airports stupefied the Cargo Cults. After watching In Time, it is obvious to me that writer/director/producer Andrew Niccol is mired in the same blithering ignorance that Mises and Rothbard pulled me out of.

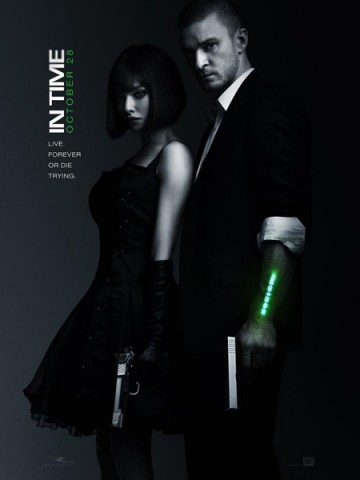

Justin Timberlake plays Will Salas, a blue-collar man living day-to-day in a world where no one ages past 25 and time is the economy’s currency. The time you have left is measured on your forearm, and you can give and receive it either by placing your wrist over a scanner, for machine/human interactions, or gripping forearms with someone, for person-to-person transactions. The world is divided into time zones and people live in the one that pertains to their occupation and income level. As long as you have time on your forearm, you can live forever, but if you go broke, you die.

One night Will Salas saves a rich man who has wandered into Dayton, the poor time zone where Salas lives, from being robbed by so-called Minutemen, petty gangsters who steal people’s time. This man, Henry Hamilton, is 105 years old and weary of being alive. He bequeaths his century of time to Will and “times out,” but due to a surveillance camera that catches only part of the action, it looks to later observers that Will has murdered Henry. Meanwhile, on the very day her son becomes a rich man, Rachel Salas (Olivia Wilde) is caught in the middle of nowhere at night with, after making a loan payment, only ninety minutes left to live. The bus fare back home has been increased to two hours and the driver will not allow her on the bus without paying the full fare up front. None of the other passengers step forward to give her a small loan, so she is left to die. A grieving Will swears revenge on the system that killed his mother.

As a fan of science fiction, I applaud Niccol’s conception of the story. This is exactly what science fiction does at its best: it explores a creative and novel concept in such a way that we are made to reflect on the world we live in, what society has become, the human condition, our hopes and fears… whatever. I would put In Time up with Moon and Children of Men as the best concepts for science fiction films in the last decade or so. It is unfortunate that it falls short of the other two in its execution, and even more regrettable how utterly uninformed the writer-director proves himself to be on topics central to the story.

There is nothing objectionable, for the libertarian, about depicting a society where the rich prey upon the poor. As is twice said during the movie, “Many must die so that some may be immortal.” Certainly that or something like it has been the ethos for many throughout history, whenever one caste preyed upon another. Neither is it objectionable to relate the class predation in the movie to our current world, because some rich, powerful interests have used government to get unfair advantages in the economy. There is nothing wrong, and in fact there is everything right, with going to an extreme to highlight this and explore the topic.

Where the libertarian cries foul is at the talk of Darwinian survival of the fittest and the implication that it is a natural aspect of capitalism. This comes out in discussions between characters and might be viewed as simply their fictional opinions, except that the world they are in reinforces the view. There is no sign of any government role in creating and enforcing cartels and monopolies, or erecting barriers to entry, or in any way maintaining through force the rigid caste system. The only indications that a government exists are the police who hunt Will and the mention of a tax on a car that Will buys. All we see are rich men approving of their own monopolies and acting without hindrance to keep them strong.

Where the libertarian cries foul is at the talk of Darwinian survival of the fittest and the implication that it is a natural aspect of capitalism. This comes out in discussions between characters and might be viewed as simply their fictional opinions, except that the world they are in reinforces the view. There is no sign of any government role in creating and enforcing cartels and monopolies, or erecting barriers to entry, or in any way maintaining through force the rigid caste system. The only indications that a government exists are the police who hunt Will and the mention of a tax on a car that Will buys. All we see are rich men approving of their own monopolies and acting without hindrance to keep them strong.

The logic of the movie, however, requires government intervention. Every child born has 25 years to live for free, at which point their clocks begin counting down from one year. The seconds and minutes of that year are slowly soaked up by the rich through high prices, usurious loans, and, when necessary, decreasing payment for work in their businesses. When Will begins liberating fortunes of accumulated time and distributing it among the poor of Dayton, the rich respond by raising prices and getting their time back.

How is this to be done without government intervention? To the economically ignorant, prices may seem mercurial, but like anything else they are governed by cause and effect, are subject to laws. There are reasons prices do what they do; rather than demonstrate the whims of the capitalist, a price tells anyone about the underlying supply and demand. How can a business just raise its prices when it decides to earn more money if people are free to go to competitors? What, in other words, has happened to the ability of a free individual to choose not to do business with someone who does not meet with his approval? As stated above, there is nothing wrong with depicting a world like this, but if that world is missing the vital element of government-granted and protected monopolies — which are the only thing that would allow businesses to behave in such a manner — then it is missing a cornerstone of logic for its world and the message it tries to deliver crumbles.

What, without government intervention, prevents the poor from forming their own banks, brewing their own coffee, setting up their own bus routes? It is a crucial component of the world and it is absent, but only someone with a little schooling in economics would even consider it. Niccol has created a world that simply cannot be. He has created a car without an engine and would have us believe it can cruise the highways at 85 miles per hour. He has given us a universe without gravity where spinning clouds of hydrogen still condense into stars. And he has no idea it is missing. Instead, characters just mouth platitudes about how the poor must be kept poor or the system will collapse. Why would it collapse? Better yet, what system is this exactly?

The movie is made with about as much skill as it deserves. Whereas There Will Be Blood is a masterpiece that a libertarian must endure if he is a cinephile, In Time is a mess about which the libertarian can smile smugly. A lack of care and thoroughness is evident throughout. There are many little problems, like continuous and deliberate close up shots of wrists transferring money to and from computers, long after the novelty of it has worn off; or claiming that someone born 50 years ago is celebrating their 25th birthday for the 25th time (take a moment to count that one out). Though small in stature, enough bugs may nevertheless turn a windshield opaque.

There are larger problems too, most of them having to do with character behavior that makes little sense but is needed to drive the plot. Why does Rachel Salas, who has lived 50 years in a world of erratic price hikes, allow herself to be drawn down to ninety minutes of life in the middle of nowhere, at night, simply to make a loan payment of 48 hours? Why does the bus driver so lack human pity as to leave her to time out? Why are banks so easy to rob in a world where money is life and people are dying of poverty? Why does Salas always seem to have an amount of time on his forearm conducive to increasing tension in the story, even when it does not make sense according to what has just transpired? Why are the police so incompetent at catching criminals until, magically, they are not?

There are larger problems too, most of them having to do with character behavior that makes little sense but is needed to drive the plot. Why does Rachel Salas, who has lived 50 years in a world of erratic price hikes, allow herself to be drawn down to ninety minutes of life in the middle of nowhere, at night, simply to make a loan payment of 48 hours? Why does the bus driver so lack human pity as to leave her to time out? Why are banks so easy to rob in a world where money is life and people are dying of poverty? Why does Salas always seem to have an amount of time on his forearm conducive to increasing tension in the story, even when it does not make sense according to what has just transpired? Why are the police so incompetent at catching criminals until, magically, they are not?

SPOILER SPOILER SPOILER

One final bit of criticism: a new type of fighting has emerged in the world where men grip forearms and try to drain each other of time. It does sound like the kind of stupid thing men would do, but Will tells a confidant of his trick for winning these fights, and the trick is absurd. Furthermore, in yet another example of behavior for the sake of the plot, a Minuteman who until then had never displayed any sort of chivalry, decides to give Will a fighting chance when he could easily have killed him. They have a time-draining match, and Will gets to use his trick!

END OF SPOILER

The conception of In Time is inspired, and might have been turned into a fine science fiction flick. The director did a good job, with the exception of one bad special effect shot using a model of a car crash, of shooting on what was obviously a small budget. The overall execution, however, makes it a forgettable film, and this fact any filmgoer can discover. The Austrian filmgoer, or anyone educated in economics, will have a second impediment to their enjoyment. However many years one has on one’s forearm, it is not worth 120 minutes to watch this film.

Comments on this entry are closed.

Geoffrey Allan Plauché October 30, 2011 @ 12:01 pm | Link

I haven’t seen the movie yet myself, but your description of the central maguffin of the movie reminds me of Hannu Rajaniemi’s The Quantum Thief (Tor 2011). A review I read describes the Mars of Rajaniemi’s novel as having an economy in which time is money and when your time/money runs out you die, like in In Time. Coincidence? Are the film and novel both drawing from an earlier work?

Matthew Alexander October 30, 2011 @ 4:50 pm | Link

Interesting that they both come out in the same year. I’m not sure what source material or inspiration Niccol had. It would be interesting to find out.

random mike October 31, 2011 @ 8:08 pm | Link

Yup, very annoying bad economics. Also I found it odd that people didn’t hate the government for forcing everyone to get death clock implants. Maybe this wealth inequality wouldn’t be so bad if there wasn’t a government policy of executing all broke people. There’s a simple explanation for Rachel’s carelessness though: High time preference.

Another book with a similar premise is Jack Vance’s To Live Forever. It’s pretty awesome despite also not making any economic sense.

Matthew Alexander October 31, 2011 @ 11:34 pm | Link

In a movie written by a social democrat, no one’s going to hate the government! 😉

I haven’t heard of To Live Forever; might check it out some time. Thanks for stopping by!

Geoffrey Allan Plauché May 11, 2013 @ 3:20 am | Link

I finally got around to watching this movie. Your review is spot on, Matthew.

The stupidity of the plotting and characterization really jumps out at you when Will’s mother is attempting to return home from paying the loan. She left herself only an hour and a half…WTF…while “knowing” that bus fare back home would then leave her with only 30 minutes of life…WTF… how was she expecting to live beyond that? Was she expecting her son to give her some time after she got home? Even so, that’s stupidly risky, especially given that he lives day-to-day himself. Clearly a case of the producers pounding viewers over the head with an ideological hammer. Then they pound you over the head again when Will is a mere second or two too late to save his mother after being given over a century of time by a wealthy benefactor.

Another thing that jumped out at me was Will’s line, “No one should be immortal if even one person has to die.” Taken a certain way, this is compatible with libertarianism. No one should be immortal if it means violating another’s rights in order to do so. But given the context of the movie, one suspects it has a more envious and vindictive egalitarian flavor, viz., no one should be immortal even if they happen to live in an imperfect world in which, through no fault of their own, even one person is unfortunate enough to die. In other words, if we can’t have a perfect world in which everyone is immortal and no one dies, then no one can be immortal.