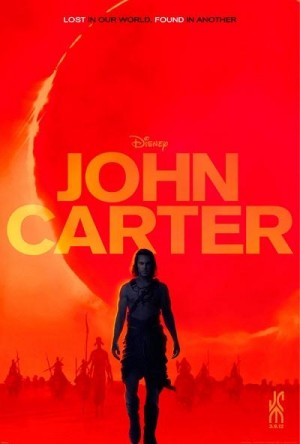

There is a certain charm to the recently released John Carter, helmed by Andrew Stanton. The two leads, Taylor Kitsch’s John Carter and Lynn Collins’s Dejah Thoris, have enough chemistry to draw the audience in; the world of Mars itself is a treat for the eyes; the basic plot is well within the bounds of standard epic adventure but perfectly sound; and many of the situations that the characters find themselves in have real potential, albeit never fully realized. In short, there was a grand story there for the telling, had there been a director capable enough to pull it off. There was not, and consequently a theatergoer is likely to leave feeling frustrated by the large gap between what was and what might have been.

There is a certain charm to the recently released John Carter, helmed by Andrew Stanton. The two leads, Taylor Kitsch’s John Carter and Lynn Collins’s Dejah Thoris, have enough chemistry to draw the audience in; the world of Mars itself is a treat for the eyes; the basic plot is well within the bounds of standard epic adventure but perfectly sound; and many of the situations that the characters find themselves in have real potential, albeit never fully realized. In short, there was a grand story there for the telling, had there been a director capable enough to pull it off. There was not, and consequently a theatergoer is likely to leave feeling frustrated by the large gap between what was and what might have been.

After a useless prologue that actually ruins the later effect when the protagonist appears on Mars for the first time, we are introduced to John Carter, a former officer of the Confederacy and current gold prospector. When the United States army tries to conscript him to fight the Apaches in Arizona, he tells them he owes them nothing and prefers to go about his own business. This defiance of the state should not excite the libertarian too much, however, because just moments before, he was busy abusing the rights of a shop owner, refusing to leave the man’s store when he wouldn’t sell. Carter’s reticence to join and fight, it turns out, is more about his bleak personal cynicism after the deaths of his wife and child than it is about a freedom-friendly moral code.

In the course of his attempt to escape the clutches of the war machine, he stumbles upon a cave where he is ambushed by a strangely dressed man with seemingly magical powers (the reason for the ambush is never made clear, though one cannot help but notice that the plot would have come to a standstill without it). After killing the ambusher, Carter takes a medallion from his cadaver and gets transported to a strange land he eventually learns is the planet Mars. He discovers he has extraordinary new powers with which he amazes some of the creatures he finds there.

Eventually, he meets a woman, a princess, fleeing an arranged marriage that could stop a war between two city-states. She wants to use him and his incredible physical prowess for her ends, which are to save her city-state from destruction without getting married; he wants to use her for his, which are to return to Earth with the help of her esoteric knowledge of his amulet. They form a distrustful alliance and adventure ensues. I’ll leave it to the reader to guess whether or not they fall in love.

Director Andrew Stanton has had success directing cartoons, but here, and not for the first time, we see a seemingly gifted director cannot make the leap from drawn images to real ones. I do not pretend to know why storytelling should so confound a man in one medium and not the other any more than I can say with certainty why some football coaches can coach in college but not in the pros, and vice versa. What I do know is that the direction in John Carter is poor, and this is responsible for many of the film’s infirmities.

A plot, as we all know, needs a beginning, a middle, and an end. So too does a scene. But even something as small as a sequence, to be effective, needs the same sort of development: an introduction, a character striving to meet a goal, and finally a resolution. Andrew Stanton, for whatever reason, did not take the time to develop his sequences in a satisfying manner. To give an example from the movie, after John Carter meets Dejah Thoris, they set out, along with a woman named Sola from a four-armed species, for what Dejah calls the Gates of Issus (I suppose this is the spelling). After a shot or two to establish that they are riding mounts over dry terrain, Sola leans over to whisper to John that she thinks Dejah is taking them somewhere else.

This revelation to the protagonist must have been the culmination of a sequence. At some point, Sola became suspicious. She saw some things to increase her suspicion. Perhaps she debated with herself as to whether she should speak to John about it or not. All of this could have been subtly conveyed to the audience, but without any build up the sequence lacks impact and things feel rushed.

The movie suffers through this sort of thing from beginning to end. While the loss of buildup for any given sequence is of little importance, the cumulative effect of so many missed opportunities is to make the film feel hurried. We are hit with one thing after another without proper setup and development, and the result is a sort of hollow sensation where some emotion should have been. Before we even have time to realize how we are supposed to be feeling, the next sequence is beginning, but it too will be overly brief. Imagine a wine taster who, instead of taking an introductory sniff and a careful sip followed by a rinse with water, gulps down one shot of wine after another with nary a pause in between. There is nothing wrong with a fast-paced adventure story, but omitting the careful setup described above makes a story artificially and detrimentally fast.

Stanton, as a director, does not stand alone with his guilt; it turns out he is guilty as a writer too, although he had some help in that endeavor. There are a number of venial sins of a scientific nature, some of which a moviegoer might be inclined to say are not sins at all. The creatures of the four-armed race have no noses, and yet their speech sounds remarkably like it is coming out of the mouth of a creature — possibly a human actor — with a definite nasal cavity. Is this too picky? Fair enough, how about the fact that Mars’ two moons, Phobos and Deimos, are shown to be about the same size in the sky as our own moon, when in reality it is no such matter. They also are always in the same place in the sky and right next to each other, even though they have different orbital periods, and fast ones at that. Shall we give them a break on the grounds of artistic license? Alright, then explain the fact that, on a parched world, settlements are far from any of the isolated oases of water, and that at no time is there ever any indication of anyone growing something to eat, nor is there any trace anywhere of recent farming.

The reader might well accuse me of being unfair. For a fantasy movie, maybe a thing like that is not important, although it does seem to me that any verisimilitude one can add will only flesh out the world and enrich the experience. If the script were brilliant and the directing top notch, I probably would not even notice these things, but an unengaged mind has time to wander and pick nits. Storytellers would do well to keep that in mind.

More substantial problems with the script include an inability, or unwillingness, to be consistent. When the plot calls for John Carter to be subdued and arrested, a single four-armed Tharg (or something like that) suffices. When it is time for Carter to demonstrate how great a warrior he is, he can take on a thousand Thargs by himself. After initially seeing his great strength on Mars, I actually began to doubt for a while if I had interpreted correctly, only to be reassured later that Carter was, indeed, inhumanly strong while on the red planet. But only if it was convenient for the script.

Another issue I had was with the way characters discovered things and made connections. Sometimes, in order to be realistic, not to mention effective, a mystery must be unraveled over time. It can be introduced in one scene, then a clue can be found in another, a deduction made in yet another, and finally the whole thing solved in a fourth. This takes the kind of patience the director has already shown he is lacking, however, and so discoveries are made under dubious circumstances and with flimsy evidence.

An example is the way John Carter deduces he is on Mars, a fact that should have been harder for him to accept, tall green Thargs notwithstanding. In the space of a single, short conversation between him and Dejah, they draw out responses from each other that lead directly to the conclusion that Carter is now on the fourth planet from the sun. It could have been a mystery spaced out over several scenes, which would be effective even though we already know he is on Mars. Instead, they bring it up and summarily dispatch it.

Other times, characters just know things because, one suspects, not knowing them would make the scene last longer than the director wanted. For instance, at one point John Carter punches a Tharg and another exclaims, without hesitation, that Carter has killed him with one blow. No pulse was taken, but he was declared dead by someone with no demonstrated medical knowledge. One hopes for his family’s sake that he truly was dead and not clinging to life in desperate need of medical care.

I have one final complaint that in a better film I would let go, but I am little moved to mercy at the moment. Lynn Collins plays her Dejah Thoris almost with a falsetto voice that many American actors use for Shakespeare or when they are trying to seem sublime. She has a husky, breathy quality and converts all her er’s to uh’s. Earth becomes Uhth, and Carter becomes Cahtuh, and it sounds silly. I would not call her performance bad, on the whole, but there were moments when it was mildly irritating. These moments usually involved an r-controlled vowel.

I could spend some time critiquing the on-the-nose-dialogue, much of it spoken for the audience rather than for the character it is delivered to, but the reader by now probably has a pretty good idea of the movie’s deficiencies. Why linger any more?

Hollywood has not exactly been hitting home runs with its fare of recent years. Science fiction has done no better than any other genre, I regret to report, and John Carter is very much a product of its times. It has some nice special effects and a lot of action, and the basic idea for the story is good. Beyond that, there is little here to enjoy. By my reckoning, 13 years have passed since the last great science fiction film. It seems we must wait at least a little longer for the next one.

Comments on this entry are closed.

Dan O. March 10, 2012 @ 6:20 pm | Link

Good review Matthew. Kitsch could have definitely been a little bit more charismatic but the flick still works due to amazing special effects and some really fun and exciting action. Sad thing is that this flick was made for $250 million and won’t make any of it back. Not a must-see by any means but still a good one to check out for the fun of it. Check out my review when you get the chance.

Matthew Alexander March 11, 2012 @ 11:40 am | Link

Thanks, Dan. $250 million… wow. That’s a big risk to take, and I think that’s part of the reason there are so many poor scripts nowadays. They try to spread risk around by taking on as many producers as possible, and of course each producer wants to have a say in the process. The result is scripts get written, rewritten, polished, changed, repolished, rewritten… all by many different screenwriters. It reminds me of the essay by H.L. Mencken where he says that our crazy universe could not have been made by an omnipotent God, but if it were made by a committee of omnipotent Gods, everything immediately becomes understandable!

Thanks for stopping by!

Fabristol March 12, 2012 @ 3:59 pm | Link

Dear Matthew,

although I don’t agree with your review I can see the weak points of the plot but, if this can be an excuse, we also need to understand that the job for Stanton was not easy as he was starting from a novel written for pulp magazines almost 100 years ago. I watched it with the same sense of wonder that I experienced with any fantasy-science fiction movies. I mean we are not talking about hard SF and we can relax our rational mind a little bit more.

Anyway, I pass by here also for another thing: what I saw in the movie was also something that we share, the libertarianism, and I wanted to know what were your thoughts about what I wrote here: http://libertarianation.org/2012/03/12/un-john-carter-libertario/

Ok, it’s in italian but Google Translate can do a nice job: http://translate.google.com/translate?hl=en&sl=auto&tl=en&u=http%3A%2F%2Flibertarianation.org%2F2012%2F03%2F12%2Fun-john-carter-libertario%2F

Thanks!

Fabry

Matthew Alexander March 12, 2012 @ 8:38 pm | Link

Mi sembra che John Carter sempre e stato di lado dei uomini piccoli, e questo significa che combatte contra il gobierno. Ma nel suo comportamento personale, a volte fa cose male, come nel esempio che io ho fatto nel secondo paragrafo. Ma tu hai ragione: credo che non inizia mai la violenza. Al finale, credo che e un messaggio misto. A volte si comporta come libertario, a volte non.

Non so come sono state le idee de Burroughs. Puo essere que fu libertario, o almeno inclinato cosi.

Mi devi scusare per mi italiano malo. No parlo cosi bene come tu in inglese, ma quando ho una oportunita di praticare…

Grazie mile per venire qui!

Fabristol March 13, 2012 @ 6:47 pm | Link

Ah che sorpresa! Capisci l’italiano. Complimenti! 😉

Dove hai imparato?

I switch to english for the english-speaking readers: I think the scene when he is in the jail at the beginning of the movie and he replies to the general is pretty “against-government and mob rule” plus his continuous rebellion against the will of the various clans.

It would be interesting to see the original work from Burroughs but I didn’t read it. Anyone that did? And what about the political views of Burroughs? I couldn’t find anything on the web.

ciao!

Matthew Alexander March 14, 2012 @ 1:04 pm | Link

Grazie! Ho imparato quando sono viaggiato in Italia. Io abitavo in Madrid, y dopo imparare lo spagnolo, l’italiano e molto facile.

I think you’re right, that there is a definite strain of individualism in the character. I never quite saw it come together as an encompassing moral philosophy, but it was at least something.

Veronica June 10, 2012 @ 2:58 pm | Link

I doubt saying this will win me any fans, but I feel a need to defend this film and story line. When it was written, many of the scientific facts which we all take for granted today were virtually, if not completely, unknown: 1912.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Carter_of_Mars

Secondly, regarding the nasal-cavity-voice and similar comments… this IS a work of fiction. Is it easier to presuppose that this is an alternate reality/universe? Most fiction takes place in a “world that would be IF…”, so does this not grant artistic license to all writers of fiction? Does writing science fiction require a background in science?

I’m not a critic by trade, but I do tend to criticize things a lot – yet I found this film to be poignant and interesting. Note for example the ties between the “red man” of the author’s time and the “red men of Mars.”

It seems to me as though, despite his time, he was very advanced: he was something of an anti-racist and an anti-sexist.

Matthew Alexander June 10, 2012 @ 3:37 pm | Link

Defend away! Nothing wrong with that.

The comment about the nasal cavity was a small point, which I granted in the review, but it fit in with the larger theme of slick, route-of-least-resistance storytelling. Rather than sit down and really plan the world out and flesh out all the details, they seemed to throw it all together. More deliberation on these things might have led to some interesting choices. The voices of the Tharks or Thargs or whatever, is an example of something that might have been done to flesh the movie out.

The problem with artistic license is that it can become a get-out-of-jail-free card. Anything in the movie that sounds a discordant note might be attributed to artistic license. It then becomes impossible to criticize. I’ll suspend my disbelief about things central to the conceit of the story, such as the dimensional leap that gets John Carter to Mars. But what is it about this universe that makes voices without a nasal cavity sound as if they had a nasal cavity? Rather than being a central point to the story, this strikes me as something that was just overlooked by filmmakers who were focused on the wrong things.

I think the point you praise it for is a part of the original work, which endures to this day and continues to entertain fans. It seems to me that the movie added very little to what was good about the book, and indeed detracted some. Just my opinion.

Thanks for stopping by and commenting!

Veronica June 11, 2012 @ 10:31 am | Link

Thanks for the fast reply, Matthew.

I appreciate your blog and opinions. 🙂