Cory Doctorow’s latest YA novel, For The Win, just might be the Jungle of the digital age — a depiction of the plight of professional gamers and their struggle to unionize and extract concessions such as better pay, shorter hours, and safer working conditions (?!) from their employers through collective bargaining. Not being an avid gamer myself, much less a professional gold farmer, I’m left to wonder if it is as poorly researched and inaccurate as Upton Sinclair’s piece of socialist propaganda fiction. I expect left-libertarians will tend to like this novel but other libertarians will not. As for myself, I struggled to finish it and do not recommend it — as much because of the writing style and quality of writing as the subject matter.

For The Win opens with a gifted Chinese gold farmer — a working gamer who plays to collect game money and items to sell for “real” money to “rich,” lazy, mostly American gamers — in China who just happens to have the Western name of Matthew. He’s attempting to strike out on his own but is visited by Boss Wing’s goons and taught a lesson. Then we meet an American Jew in Los Angeles who goes by the Chinese name of Wei-Dong and moonlights, against his parents’ orders, as a gold farmer with some online buddies in China. Next, we’re introduced to Mala, aka General Robotwallah, a poor Indian girl with a talent for strategy and leadership, who is hired by a mysterious man to use her “army” to harass gold farmers in-game because they allegedly disrupt the game for honest, paying customers.

Before long we’re introduced to Big Sister Nor, a mysterious new figure on the scene who is out to organize working gamers into a union to fight corruption and improve their circumstances. As the novel progresses, we’re introduced to more characters, mostly in China and India, where the bulk of the action takes place. Perhaps the most notable is a female Chinese underground radio host who caters to the factory girls, giving them advice and urging them to stand up for themselves, while she dodges police raids, moving from safe house to safe house under a series of false identities.

One of the themes of the novel is how difficult it has been historically for workers to organize and how the internet (including social media and online games) provide game-changing tools for organizing labor. There is much truth to this, though I am skeptical that even the myriad tools of the internet can allow a voluntary global union to pull off anything like the ambitious scheme Cory’s protagonists endeavor to carry out in the novel. Although Cory has characters voice the usual skeptical objections to the efficacy of a voluntary global union, I don’t think he adequately addresses the difficulties such a union would face even in the digital age. Without state-backed coercion (directed at businesses, scabs, and their own members), how much power would a union really have, particularly spread out over the globe? Sure, gamers have an advantage in that they all work virtually in the same place — but still…

To Cory’s credit, however, he does depict a truly voluntary union whose leaders welcome freely competing unions in the market. The International Workers of the World Wide Web (IWWWW) or Webblies, as they call themselves,1 even eschew a formal hierarchy. The de facto head of the union at one point exclaims to her followers, “I’m not magic. … You all lead yourselves.” They also, admirably, do not seek compliance with their demands through legislation or regulation. Instead, they engage in self-help. Libertarians may find some of their methods questionable, however.

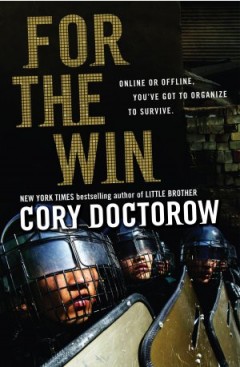

Cory’s novel bears the tagline “Online or offline, you’ve got to organize to survive” (or some variation thereof) and Cory himself admits that, as with Little Brother, this novel is meant to do more than just tell a story. Like Makers and Little Brother (both of which I have reviewed), and perhaps all of Cory’s fiction, For the Win is a political novel that aims to educate and promote a message. It is

a book about economics (a subject that suddenly got a lot more relevant about halfway through the writing of this book, when the world’s economy slid unceremoniously into the toilet and got stuck there), justice, politics, games and labor. For the Win connects the dots between the way we shop, the way we organize, and the way we play, and why some people are rich, some are poor, and how we seemed to get stuck there.

The timing of the writing of the book unfortunately led Cory to infuse a good deal of it with thinly veiled commentary on the recent financial crisis, but more on this later.

These educational and political aims tend to weaken the quality of Cory’s work as literature. In what I’ve read, Cory’s authorial voice is thinly disguised. His characters periodically, and all too frequently, use every opportunity to provide the reader with an infodump lecture (yes, one does get the impression they are more often than not for the reader’s benefit, not that of the other characters), often at length, and sometimes mentioning something more than once through the course of the story. This can be tedious and jar the reader out of the story. I felt this effect was mitigated somewhat in Little Brother due to its first-person recounting-of-events perspective, an improvement on the third-person-limited perspective in Makers. It also works better when Cory sticks to explaining technology and geek culture.

With For The Win, however, Cory goes way off in the opposite direction. It’s in third-person but frequently goes off into omniscient, a seldom-used perspective these days. Some of his characters go on obvious infodump lectures from time to time. But as if that were not enough, Cory often doesn’t even try to mask his authorial voice with a character. There are seemingly random infodump lectures that go on for pages, from no particular character’s perspective, not even an identifiable narrator. One minute you’re reading along in one character’s perspective (more or less) and then suddenly, after a chapter break (just a small space with the first few words of the next unnumbered chapter in bold), you’re dumped into a perspectiveless sidebar-like tutorial that sometimes borders on a rant. These seem to be meant to explain the theory or inner-workings or background behind something that is about to be touched on in the upcoming action. It is as if you are watching a movie with Cory Doctorow himself and he turns out to be one of those people who likes to control the remote so that he can press pause once in a while to turn to you and explain what is about to happen. Is it really necessary to disrupt the pacing by having me read a five-page lecture on “Coase cost?” Srsly.

A negative side effect of letting educational and political aims supersede art, and more particularly of Cory’s omniscient infodump lectures, is to make a character’s thoughts, emotions, and actions fail to ring true. One example of this that particularly struck me was a scene that comes after lectures on the psychology and economics of financial trading and how people get conned. As the Chief Economist of Coca Cola Games (?!), who in his youth formulated miraculous equations that could reliably tell him how much something was currently over- or underpriced by the market and therefore due for a correction, wrestles with the decision of whether to quadruple down on margin on some “fully hedged, no-risk, sounds-too-good-to-be-true” investments that he’s just been informed by his broker are “temporarily” not doing so well, we’re given a dramatic illustration of the internal conflict between a person’s rational side, which knows full well that this is stupid, and his emotional side, which is driven by fear and embarrassment and envy and the like to make stupid decisions and even dig the hole deeper. But even this illustration is more stated than shown. It fails to ring true in part because one senses an ulterior motive, that the character is thinking, feeling, and acting as he is to fit a preconceived plot or make a point.

A few other things that bothered me: Having read three Cory Doctorow novels now, I’ve noticed that Cory tends to reuse certain plotpoints (see previous reviews) and descriptions: e.g., “nuclear-hot” food, “boggled,” “as obvious as a boner at the chalkboard.” Some, like the first two descriptions, evoke that ever-present adolescent excess in Cory’s novels, which is fine in YAs with adolescent characters, but even his supposed adults act the same way. This excess manifests in exaggeration of stereotypes as well, such as his rather gross descriptions of nerd-gamers. The third description seems rather unnecessarily crude, but hey! I guess it’s what the YA audience wants?

Another thing that bothers me is Cory’s penchant for postulating improbable corporate mergers and products. In Makers, it was Kodak and Duracell merging and becoming a micro-venture-capital firm. In For The Win, I just don’t see a Nintendo-Sun actually happening or Coca-Cola becoming a major MMORPG company, running something like a dozen big, oddball, ‘toony games that don’t seem to have any relation to their beverage line whatsoever.

And there are some rather abrupt transitions in For The Win (cwidt?), such as when a character visits a hospitalized friend with whom Cory hinted romantic tension; the character doesn’t spend any time by her side, take her hand in his, weep over her, speak to her sleeping or comatose form about how much he cares about her, or anything like that — no, instead he rants and raves a bit about how he’s going to make the bad guy pay for beating her near to death, then in the span of a one-sentence description by Cory, he runs off to save a virtual economy from the brink of collapse (part of the aforementioned grand Webbly scheme).

It’s not all bad, however. When the pacing isn’t being derailed by authorial, 3rd-person omniscient infodumps great and small, there’s actually an entertaining story to be read. There are even some points in which Cory comes close to some profound insights — if only he were to take them to their logical conclusions:

His lectures on gold and inflation flirt with the realization that gold is sound money and that governments wreck economies and harm people, particularly the poor, with their fiat money and their inflationary policies. Cory even recognizes that there are three ways for governments to acquire money to spend on things — taxation, borrowing, and inflation — and that the last is a particularly tempting and devious way for governments to fund wars. But if you’re expecting Cory to identify government as the main culprit behind the recent financial crisis and call for the abolition of the Fed and a return to the gold standard, don’t hold your breath.

Cory realizes that businesses are generally only able to abuse their employees and get away with it with the sanction and support of government. “The corrupt businessmen buy corrupt policemen who work for corrupt government.” But like any left-liberal, I don’t think his solution is to limit or abolish government. Despite government agents being responsible for the lion’s share of the beatings, imprisonment, maiming, and murder in For The Win, the plot centers around workers trying to extract some relatively modest concessions from their employers.

This utter lack of radicalism pervades all three of Cory’s novels that I’ve read and reviewed. The ultimate source of the problem is not properly identified, much less addressed. The goals his characters set for themselves, or actually achieve, are ultimately modest reforms at best. And in For the Win, the antagonists with whom his characters engage, as if with the only obstacle that can be overcome, are businessmen. Government seems almost like a unmovable force of nature, a force that will once again be benevolent if we can just pressure businessmen to concede to our demands and stop corrupting it to use against us. Utter naiveté. It makes me wonder how this book was selected as a finalist for the Prometheus Award.

But I was supposed to be discussing good aspects of the book, brushes with insight and whatnot. I’m trying, I really am. There’s a clever criticism of implicit social contracts as unreliable, unenforceable, and prone to being re-interpreted by the stronger party as he likes (à la “I am altering the deal. Pray I don’t alter it any further.“). He points out how gamerunner interventions in their virtual economies are prone to making things worse, that “there are ten zillion ways to get this wrong and so few ways to get it right.” These insights apply to government and government interventions, but for some reason Cory is no libertarian.

Okay, I’m all out.

Oh, wait, there’s one more: Cory is fairly good on intellectual property and piracy. For The Win does manage to hammer home the point that it is actually cheaper and more profitable to embrace piracy, gold farming, and the like rather than waste money and resources fighting them.

I might as well end on a negative note and highlight the really awful political and economic ideas I’ve passed over so far.

Early in the book we’re treated to some Marxist rhetoric suggesting that the capitalist is not productive and that he skims off the surplus value of the worker’s labor. Oh sure, Cory has one teenage protagonist voice token objections to these ideas and the possibility of a voluntary global union being successful, but the union organizer responds in that familiar left-liberal elitist, condescending, oh-you-poor-naive-child manner. There is talk of living wages and of safe working conditions (for gamers?! what’s dangerous about that job?). Workers complain about the game companies having control over their own games; heaven forbid!

A distinction is made between working for a living and owning for a living, as if, again, the latter don’t ever do anything productive and capitalism is just another form of feudalism — wealth is simply inherited and those who are historically disadvantaged can never catch up without intervention; to the extent that this is true today (and it doesn’t yet hold a candle to precapitalist historical conditions) it is because of government interventions in the economy; it is not an inherent feature of free markets.

In the second omniscient infodump lecture chapter, we’re taught that arbitrage is merely “a way to get rich without making anything anyone needs or wants, but you have to be fast.” Cory then proceeds to present us with a disingenuous argument meant to cast arbitrage in normal market situations in a bad light. He starts off with the hypothetical example of neighbors, one of whom, Mrs. Hungry, wants a banana and is willing to pay $.50 for it, and another, Mr. Full, has a bunch of bananas and is willing to part with them for a mere $.30 apiece. Instead of doing the neighborly thing and putting them in touch so that they can make a deal amongst themselves or simply buying a banana and giving it to Mrs. Hungry, you buy up all of Mr. Full’s bananas and sell them to Mrs. Hungry at a $.20 markup. You greedy, selfish, bad bad person, you!

That’s what arbitrage is, dontcha know, so naturally you should have a similar negative reaction to arbitrage transactions among strangers in normal market situations as you (should have) had to the unneighborly fellow. To top things off, we’re treated to an even more ludicrous claim: “if you and your arbitrageur buddies were to vanish tomorrow, the economy and the world wouldn’t even notice.” Nevermind the arbitrageur’s useful role in facilitating trade and pushing market prices toward equilibrium.

Despite what I wrote about gold, fiat money, and inflation above, Cory’s economist character, Ashok, doesn’t really understand why anyone values gold. “Gold is such a useless thing, you know? It’s heavy, it’s not much good for making things out of — too soft for really long-wearing jewelry. Stainless steel is much better for rings.” Yeah, guys, buy your significant other a steel ring as a gift and tell her that. I dare you. Heck, tell that to all the people throughout history who used gold as a medium of exchange in the form of coins and bars because it is easily recognizable, divisible, portable, rare, and valuable as a commodity in its own right, prized for its beauty, etc., etc.

Cory goes beyond Austrian subjective value theory, in which human valuations are relational and grounded in reality, in the actual utility goods have for people due to their natures. From Cory one gets the impression that people value things inexplicably, they just do, and it’s often wondrous and strange and fun to lecture about. Ashok and Cory do understand the value of gold in limiting government’s ability to inflate the money supply at least.

Finally, a word about Cory’s understanding of the economy, particularly financial markets, which suffuses the book. He has a decent understanding of business and market processes at a superficial level, but ultimately he views the economy almost like a Keynesian. Inflation and deflation, bubbles and busts are essentially driven by animal spirits: shifting feelings of confidence, envy, and fear. He’s enamored of behavioral and experimental economics as well, but what he’s picked up from these just dovetails into his explanations of how the economy and financial markets essentially work, which boils down to the cyclical but otherwise unpredictable whims of the animal spirits.

If all of this hasn’t dissuaded you from reading For The Win, you can read for free in various digital formats available on Cory’s website or you can buy it in print from Amazon.