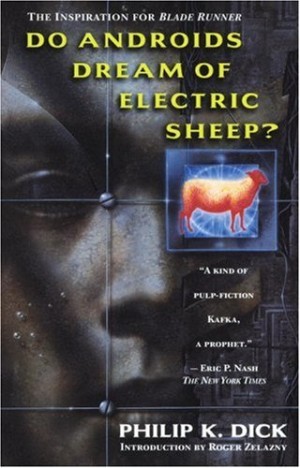

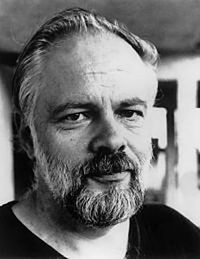

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? is probably Philip K. Dick’s most famous work, given that it was turned into one of the most respected science fiction films of all time. I do not hold to the absolutist opinion that the book is always better than the movie, but after one read of the book and many viewings of the movie, I am inclined to say that, in this instance, the book is at least as good and in some respects is better.

Rick Deckard, along with numerous other unfortunate souls, has been left behind on Earth, an unhealthy wasteland from which anyone of means has migrated. He is the number two man assigned to retire rogue androids who try to pass themselves off as human. The androids, however, prefer to remain alive.

Deckard makes a modest living, but when the number one guy is nearly killed by an android, he assumes the responsibility to retire a group of six of them, seeing in the job an opportunity to make some much-needed cash. Insert canned line about things not going as planned. Insert second canned line about the job being more than he bargained for.

As I expected, the clownish dialogue and behavior, unnecessarily detailed descriptions and lengthy back stories injected into scenes immediately after a character’s introduction — the slipshod method by which so many authors introduce and develop their characters — is absent. Instead, we meet people who feel and act real, and we come to know them as we would anyone else: by how they act, what they say, and what is said about them. They move about in an exotic land but act in accordance with their human goals and abilities.

What I found surprising was how good the plot was. There is a satisfying quantity and variety of dramatic interactions, various obstacles to overcome, a sufficiently grand and tense third act… everything an eager reader could hope for. I did not expect a poorly wrought narrative, but given some of the difficulties I found in The Man in the High Castle, I thought that maybe character and setting were Dick’s strengths, not plot. The movie, as good as it is, strikes one as underplotted, and I assumed this was due to a deficiency on the book’s part.

The truth is, Ridley Scott had a perfectly good script already made for him when he set out to make Blade Runner. Why it was so altered — perhaps watered down is more accurate — I cannot fathom, but the movie wound up with an inferior story. There are all sorts of scenes and story-paths in the book that would have been as easy to film as anything else and that would have improved the movie.

SPOILER SPOILER SPOILER

Early in the investigation, Deckard is told by his chief that a man is coming to observe his work. This man turns out to be an android who tries to kill Deckard.

Deckard tries to test what he believes to be an android, but the test does not go well. Is she deliberately and cleverly sabotaging his efforts, or are her actions and excuses valid?

Deckard is arrested by a cop. When he tells the cop where he works, at the police precinct, the cop does not believe him, tells him there is no police precinct there. Instead, the cop takes him to an alternate precinct, one that Deckard has never heard of. Deckard begins to believe he is surrounded by androids.

Deckard joins forces with another cop who starts to suspect himself of being an android. He is, however, dedicated to eradicating androids and suffers a crisis.

Deckard has a very compelling rendezvous with an android who tries to inhibit his will to retire androids.

END OF SPOILERS

Each one of these scenes, and a few more besides, is an excellent scenario and might have been used to good effect by Mr. Scott. I can only wonder that he left them out of the story.

There is a lot for libertarians to ponder, though there is no indication in the novel that this angle ever occurred to Dick. The androids are incapable of sympathy, but they still seem to experience emotion and have a desire for self-preservation as well as cognitive abilities roughly equal to that of humans. What, then, of the rights of androids?

Murray Rothbard talked about rights for nonhuman beings only a little, but what he did say leads me to conclude that he would have advocated for android rights, so long as they respected them in others. And the truth is, throughout the novel the androids do bad things usually in response to something done to them, or because of the desperate situation they are in through, it seems to me, no fault of their own.

It is never clear why androids must be retired if they escape their slavery. Deckard himself never questions it, and neither do the androids. It is a fact of life that both sides must cope with, and cope they do, without introspection. Were Dick a bit more libertarian, this might have been a fruitful avenue of pursuit.

There is one aspect of the book that was, sagely, left out of the movie. There is a new religion that has come to predominate in the society, much of it having to do with obsession with animals, which have become rare in the wasteland that Earth has become. While some aspects of it fit in well with the story — giving us the title, for example — others are more distracting. Why were these distracting elements in the story, doing so little yet being constantly referred to? There is an allusion to it near the end of the book, a connection between Deckard and a religious figure, but I cannot help but feel that I missed something. It has all the hallmarks of an important point, since Dick went out of his way to create a scene to show it to us, but whatever it was eludes me.

Scott omitted these things from the movie, and they might have been left out of the book without harming it. Nevertheless, their presence is only a small puzzle, a mild annoyance, in what is otherwise a fine tale of science fiction. Though the movie has an atmosphere that has rarely been matched, the book has the better plot and I might have to incline towards it for that reason.