There are many elements of science fiction that find their way into stories that are not science fiction. Many times, enthusiasts of the genre will try to claim these works as part of the family. Atlas Shrugged and 1984 are examples. The same thing happens, only more frequently, with noir. Sometimes, the mere presence of a morally ambiguous protagonist is enough for a piece to be so labeled.

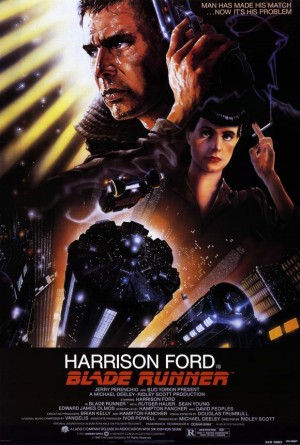

Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, however, is a rare work — quite possibly unique — that may fit both bills. While perhaps not classically noir, there is no denying a strong noir presence, and its science fiction credentials are beyond question, what with the flying cars and androids, called replicants, and off-world colonies. As a devotee of both genres, I quite naturally am a fan of the director’s third film, but watching it is an experience both frustrating and pleasant. It is a good movie, but not the great one it could have been.

Alien, Scott’s second feature, is a masterpiece whose best form made it to the silver screen. One simply cannot imagine a better version. Blade Runner, however, is a movie whose perfect version was never realized, whose potential was never reached. That mirage of the ideal Blade Runner intrudes on my thoughts every so often, and I find myself reaching for the DVD, thinking that perhaps this will be the viewing where I get it, where I notice that missing part or make that important connection.

It never works out that way. As usually happens in life, experience trumps hope. The movie simply is not as good as it ought to have been, and the reason is the plot. This is all the more tragic given that Philip K. Dick, in the novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, had already provided a first-rate plot that was later diluted over multiple drafts of the screeenplay.

Harrison Ford plays Rick Deckard, a blade runner, a police detective who hunts down and kills replicants. When a group of four replicants go on a killing spree and escape to Earth, he is tasked with finding and killing them. Along the way, he meets a woman who turns out to be a replicant, and develops feelings for her.

The premise is simple, and the plot adds only a little complexity on top of it. Not that a plot needs complexity to be good, but it does need peaks and valleys, obstacles and more obstacles, twists and turns, dramatic interactions. It would be unfair to say that the movie has none, but when it is over one has that feeling of an itch not fully scratched. Blade Runner is like a one-course meal whose lone dish is superb, but lacks the variety and quantity needed to fully satiate one’s palate.

As with the book, there is never any attempt to explain why the replicants must be taken out. While the particular replicants involved in the movie have committed capital crimes, there is no question of rights, habeas corpus, and a trial by jury; for them there is only assassination. This is the fate that awaited them as soon as they escaped; the murders were committed essentially penalty-free. Other replicants are treated the same, whether or not they have committed crimes.

It is accepted as a fact of life, questioned neither by human nor replicant. The pseudo-humans are none too happy about it, but they do not bother to write a declaration of the rights of replicants, nor mount a simple verbal defense of themselves, nor even complain much about their lot in life. Their main gripe seems to be their short programmed lifespans, not the fact that the police are bent on making them even shorter. I do not find it strange that such a society should evolve, but that it never occurs to any storyteller involved with the world to question this feature or entertain the possibility of rights for sentient life other than homo sapiens I find curious, a missed opportunity.

Where Scott misses no opportunities is with the craftsmanship of the work. The shots are exquisite and pieced together at a deliberate pace. The music adds a noir feel to go with the mood lighting. Many of the prominent features of the book’s world remain in the movie, though less conspicuously, creating a rich tapestry of details for the story’s background. The sets are evocative. Though the acting is not as uniformly spot-on as in Alien, Harrison can pull it off all by himself, and he gets help from a few strong supporting roles.

In most categories, Blade Runner meets or exceeds what one expects from a classic, an elite work. The only thing holding it back is that there is not enough in the plot to give that full sense of satisfaction one gets from a good, well-rounded story. Perhaps Ridley thought the book was too much, that it needed to be trimmed down for cinema.

Considering what the movie could have been is an exercise in frustration, but even so it is as good as or better than any science fiction film of the last 12 years. It rewards multiple viewings; I just wish the reward were even greater.