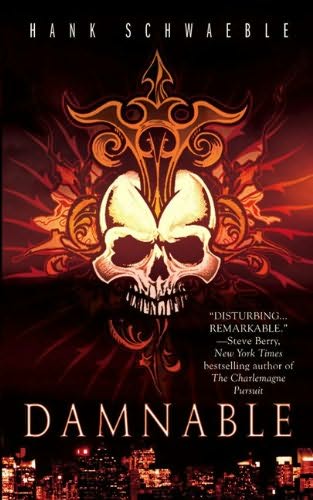

Hank Schwaeble

Damnable, by Hank Schwaeble, has been called noir, but anyone who has seen The Third Man, Double Indemnity and The Asphalt Jungle will see no more than a tenuous connection to what noir originally was. Just like the word libertarian often gets applied to anyone who is pro-choice on two or more issues, noir gets thrown at any tale with a dark atmosphere, a detective and/or so much as a single morally ambiguous character, resulting in an abundance of wrongly labeled people and stories. Damnable, winner of the 2009 Bram Stoker Award, is not noir any more than Bill Maher is a libertarian; it is a mix of detective tale, supernatural story full of demons and cultish rituals, and MMA-style fighting and action.

Damnable, by Hank Schwaeble, has been called noir, but anyone who has seen The Third Man, Double Indemnity and The Asphalt Jungle will see no more than a tenuous connection to what noir originally was. Just like the word libertarian often gets applied to anyone who is pro-choice on two or more issues, noir gets thrown at any tale with a dark atmosphere, a detective and/or so much as a single morally ambiguous character, resulting in an abundance of wrongly labeled people and stories. Damnable, winner of the 2009 Bram Stoker Award, is not noir any more than Bill Maher is a libertarian; it is a mix of detective tale, supernatural story full of demons and cultish rituals, and MMA-style fighting and action.

This is not to denigrate the work — or Bill Maher — but merely to put it in its proper category. As a story it is a modest success, not profound perhaps, but also without pretensions of depth and nuance. On the first page, a character muses, “Coffee was like pizza and sex — no matter how bad it was, it was usually still pretty good.” In other words, the author is decent enough to tell us straight away we will not be wrestling with complex ideas and weighty issues. When a zombie attacks a few paragraphs later, it is the author letting us know what we will be doing.

I enjoyed my time with the novel, which I believe is all the author ever wanted for his readers. I know I enjoyed it because I put my book mark in the sequel as soon as the last page was turned. The main character, Jake Hatcher, is something more than one dimensional, interesting from the outset. His situation is intriguing, his history morally ambiguous, and his abilities perfect for the action to follow.

We first meet Jake as a convict in a military prison. One of his jailors has it out for him, and Jake suspects his cellmate has been recruited to pick a fight with him, to get him in trouble so his term can be lengthened. There is also another trap his jailor has set for him, and while he tries to navigate these he gets a call from his mother telling him his brother has died, an event we saw in the prologue.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

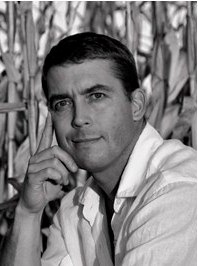

Ted Lacksonen

The Eagle Has Crashed is the provocative title of Ted Lacksonen’s first novel. Known as The Country Thinker on the Internet, Mr. Lacksonen has written a tale of what may be in store for this country if we don’t sober up and start walking the straight and narrow. His main concern is our mounting debt and how that could destroy our financial future and, through a chain reaction, tear our nation apart.

The near-future story follows the fortunes of many different people as a time of tribulations begins. Though a few high ranking officials do play a role, including the President of the United States, most of the characters are ordinary citizens in central Ohio, where Mr. Lacksonen lives. When the economy begins to crack, a series of mishaps, tragedies and catastrophes like a crescendo of disaster wracks the country. People become desperate and respond according to their nature, some digging in to take care of themselves, others making sacrifices for what they see as the good of the country.

Though I have some sympathy for it, I am not fully in agreement with the message of the book. I do not believe debt would be the prime driver of an economic collapse. Rather than close the deficit and pay down the debt, I would prefer to see government spending come down. I would even look favorably on, or at least view as an improvement, a budget deal that increased the deficit if it also cut revenues — that Washington euphemism for stolen money — and spending (a real cut, not the fake cuts we have been hearing about). Nevertheless, I do not argue that debt is trivial or innocuous, and it is nice to see an author use it as a backdrop for his tale.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

William S. Kerr

William S. Kerr’s first novel, The Shield that Fell from Heaven, is a delightful surprise. It is not a book I would have expected to find from such a small publisher, Groton Jemez Publishing, and it is not a book I would have expected to find in this century. Indeed, had I been told it was written in the 19th, I would have believed it, at least until I came to a more modern science fiction element.

William S. Kerr’s first novel, The Shield that Fell from Heaven, is a delightful surprise. It is not a book I would have expected to find from such a small publisher, Groton Jemez Publishing, and it is not a book I would have expected to find in this century. Indeed, had I been told it was written in the 19th, I would have believed it, at least until I came to a more modern science fiction element.

It is written as the journal of a Frenchman who, in 1861, on the eve of our War for Southern Independence, comes to America as a war correspondent. Edouard de Grimouville is a minor noble whose House has lost most of its fortune. In the neutral state of Kentucky he finds political opinions of all stripes, a woman to fall in love with, and more adventure — and of an unforeseeable sort — than he was looking for.

Kerr writes with the prose of a bygone era, and does so convincingly, like a foreigner who has mastered a native accent. As a lover of that more sensuous, patient style, I was quite happy to immerse myself in it and would have gotten some enjoyment from the experience even if that had been the only appetizing aspect of the novel. There is, of course, much more to enjoy.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

I found Hyperion to be the kind of book I hope every book will be when I first crack it open. This came as a mild surprise, given that it is modeled after The Canterbury Tales, in which a group of pilgrims take turns telling their stories of how they came to the pilgrimage. It is not a structure that thrills me, but the book is so well written, the world so well-conceived, and the stakes so unique and important that I found myself agreeing with the general critical acclaim that has been heaped upon it through the years. It is unquestionably one of the best scifi novels I have ever read.

In the world of the story, Earth has long since been destroyed and humans have colonized much of the galaxy. Most worlds are connected by worm holes, though a few exist outside this system; one such world is Hyperion. On Hyperion lives the Shrike, a mysterious creature that lives to kill. It is customary for some to make a pilgrimage to where the Shrike wanders, and when the Shrike finds a group of pilgrims it kills all but one member who may then petition it. This custom, at the time of the story, has almost been abandoned, but a group is put together for one last pilgrimage as a hoard of Ousters — nomadic humans who have taken to living in zero gravity and evolved into a different species — nears the planet and prepares to attack.

The setting for the story is richly imagined, on a level with Dune, Middle Earth and other such classics. The tales of the various pilgrims take us to many different worlds, and each becomes, as it is presented to us, distinct through the grand conception and the fine details. The planet of Hyperion is especially well conceived, with enough variety, plausibility, history and ingenuity to make us wonder if it might not actually exist somewhere. It holds the Time Tombs, grand and enigmatic structures that are moving backwards in time. There is a sea of tall grass that resembles a proper sea from afar, but none may cross it on foot because of the serpents that inhabit it. There is the abandoned Poets’ City, whose inhabitants were slaughtered by the Shrike. The other worlds are also differentiated. That old cliché in scifi in which each planet has one defining characteristic — and probably one culture, one language, one government — has given way to something more realistic in recent decades, and Hyperion is a prime example of this welcome trend.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

Robert Heinlein’s first Hugo Award winner was Double Star, a work that garners him far less attention today than his other Hugo winners. A reading of the novel will make obvious the reason for this: it is simply not as good. This is not to say that the book is poor, but for it to have won the Hugo Award in 1956, one must suppose either that it was a weak year for science fiction or that giving it the award was a mistake, akin to giving the Oscar to American Beauty or Shakespeare in Love.

It is something of a mystery to me why the novel does not amount to much. The protagonist has a distinct and interesting personality and the idea for the story holds promise. The prose is spare but efficient as you would expect from a Heinlein piece. What went wrong is that the plot is underdeveloped, a fault that would seem to be easily avoided, especially with a veteran author if he cares enough to put the effort into it. A writer needs to squeeze out of a story idea its potential, like one wrings the juice from an orange, and this is not achieved in Double Star. Given that The Puppet Masters came out a few years earlier, its weakness cannot be explained by an author who had yet to come into his own as a storyteller.

The main character is Lorenzo Smythe, an actor in the middle of some lean times but who preserves his pride and thespian affectation, though not to the point of becoming a caricature. He is offered a top secret job to impersonate a kidnapped Martian politician, Joseph Bonforte, until the man can be recovered. At stake is the peaceful equilibrium of human society.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

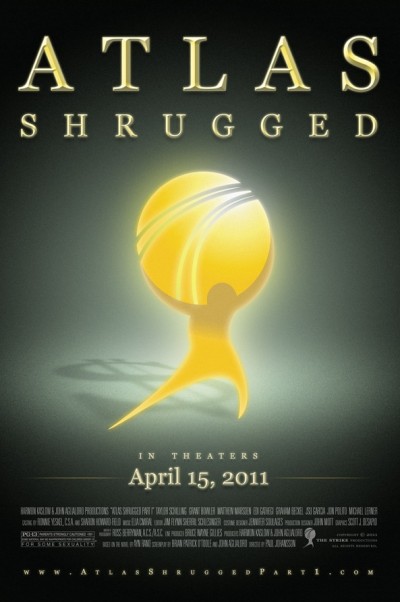

In Ayn Rand’s novel Atlas Shrugged, the first time we meet Dagny Taggart is on the Taggart Comet. The scene comes alive as Rand’s pen reveals the details such that the reader feels as if he is there. When Dagny awakens from a nap to discover the train has stopped, she gets off to investigate. Ayn Rand writes:

In Ayn Rand’s novel Atlas Shrugged, the first time we meet Dagny Taggart is on the Taggart Comet. The scene comes alive as Rand’s pen reveals the details such that the reader feels as if he is there. When Dagny awakens from a nap to discover the train has stopped, she gets off to investigate. Ayn Rand writes:

There was a cold wind outside, and an empty stretch of land under an empty sky. She heard weeds rustling in the darkness. Far ahead, she saw figures of men standing by the engine—and above them, hanging detached in the sky, the red light of a signal.

I have often thought Rand would have made an excellent director, and in that single paragraph we can see some of her talent. She appeals to three senses and evokes compelling images in our heads. A director, location scout, sound engineer, set designer, and cinematographer intent on filming such a scene have half their work done for them already. Let us hear the weeds but not see them; let us see Dagny shiver once and hold her coat tighter to her body; let us see a long shot of silhouettes of men bathed in red light from the stoplight that seems to float in the dark sky above them. The appropriate shots present themselves, practically instructing the director.

Before the stop, Dagny hears a brakeman whistling a tune she just knows was composed by Richard Halley.

“Tell me please what are you whistling?”

…

“It’s the Halley Concerto,” he answered, smiling.

“Which one?”

“The Fifth.”

She let a moment pass before she said slowly and very carefully, “Richard Halley wrote only four concertos.”

The boy’s smile vanished… “Yes, of course,” he said. “I’m wrong. I made a mistake.”

This early scene, which I find excellent and a great mood setter for the rest of the book, is absent from the movie. So too is any trace of the talent for storytelling present in it.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

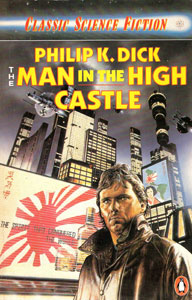

Author Philip K. Dick

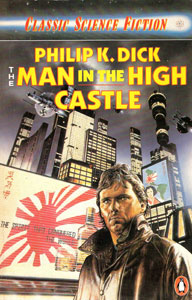

It seems to me that of the two most important elements of a story, plot and character, plot seems to be more masculine and character more feminine. That is to say, a story for men, if it skimps on either of the two, is more likely to skimp on character, while a story for women will shortchange the plot. The best stories, of course, are strong in both categories. Science fiction, being a more masculine genre — in fact the only genre of fiction whose readership is more male than female — has traditionally been solid on plot and hit or miss with the characters. There are exceptions, as one would expect, and Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, a Hugo Award winner, is one of these.

The story takes place in what was the present day when the novel was written, 1962, but in an alternate timeline where Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan won World War II. The United States has been carved into puppet governments; Germany has sent astronauts to Mars, drained the Mediterranean for farmland and committed multiple genocides; Japan controls the west coast of North America, having become a cultural as well as political hegemon.

It is a marvelous setting, both in conception and in description. Dick’s prose makes it come alive with a few deft touches here and there, sparse but effective. Whereas in most stories the setting serves as a place for the plot to take place, the reader here gets the sense that the plot is just something to have happen in the setting. The world and its characters are the point; what they do in the narrative has less importance.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

Damnable, by Hank Schwaeble, has been called noir, but anyone who has seen The Third Man, Double Indemnity and The Asphalt Jungle will see no more than a tenuous connection to what noir originally was. Just like the word libertarian often gets applied to anyone who is pro-choice on two or more issues, noir gets thrown at any tale with a dark atmosphere, a detective and/or so much as a single morally ambiguous character, resulting in an abundance of wrongly labeled people and stories. Damnable, winner of the 2009 Bram Stoker Award, is not noir any more than Bill Maher is a libertarian; it is a mix of detective tale, supernatural story full of demons and cultish rituals, and MMA-style fighting and action.

Damnable, by Hank Schwaeble, has been called noir, but anyone who has seen The Third Man, Double Indemnity and The Asphalt Jungle will see no more than a tenuous connection to what noir originally was. Just like the word libertarian often gets applied to anyone who is pro-choice on two or more issues, noir gets thrown at any tale with a dark atmosphere, a detective and/or so much as a single morally ambiguous character, resulting in an abundance of wrongly labeled people and stories. Damnable, winner of the 2009 Bram Stoker Award, is not noir any more than Bill Maher is a libertarian; it is a mix of detective tale, supernatural story full of demons and cultish rituals, and MMA-style fighting and action.