High Desert Barbecue, by libertarian author and columnist J.D. Tuccille, is a fun romp through the dry country of the southwest. The protagonists are libertarian and manage to slip in many an observation about life and the government. The antagonists are government agents, usually environmentalist wackos and bumbling idiots to boot. Mr. Tuccille does not try to hide his colors, but whatever the reader’s are he will at least find some humor and adventure in the tale, and if he is libertarian some satisfaction as well.

The story concerns a plot by environmentalists to burn out animals — humans especially — from northern Arizona so that plants may take their place at the top of the food chain and not be bothered by inferior creatures. The irony of these mammalian Forest Service enviros passionately fighting for plants, against their own kind, is thick throughout the book. One can sense the author’s amused disdain and the pleasure he takes at the antics of these defectives.

Their act of arson — referred to as “The Carthage Option” — is witnessed and filmed by Rollo, his friend Scott, and Scott’s girlfriend Lani. A chase through uninhabited territory follows, while the fire burns. The three protagonists are desperate to get the footage uploaded to the internet so that everyone can see what the government is up to. The Forest Service hippies, a group of incompetent boobs who are good for a couple dozen chuckles through the course of the story, pursue them, determined to keep the intelligence from reaching Youtube but having difficulties getting out of their own way during the chase.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

The Stygian Conspiracy, by first-time author Kodai Okuda, is a bulky tome and quite an undertaking. The myriad pages are brimming over with a story of action, science fiction, and even some horror elements. It is a tale on a grand scale, both in time and space. Not content with a small moment or two with a libertarian flavor, the story tackles the big issues and concepts and makes no apologies, without forgetting that the plot and characters come first.

The story transpires in a future in which the human race has spread out through the solar system and taken some tentative first steps towards exploring other star systems. The population is roughly divided between the Eastern socialists and the Western capitalists, the latter of the two having newly emerged as a power again on the world, or better yet solar, stage. That description and its implicit chauvinism make me cringe even as I write it, but Okuda does much better with the characters, creating roles that defy the simplistic expectations set up by that line drawn down the middle. There are good bad guys and bad good guys and even, I think, a little room for debate.

It is a bold concept and a wild ride. There are space battles and daring personal missions, enmities and romances, betrayals and tough decisions. It lacks nothing of the right ingredients to leave a voracious reader with a satisfied feeling upon completion. If the reader wants nothing more than an epic tale of adventure with some characters to care about, he may well come away from The Stygian Conspiracy without complaint.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

A revised vision of basic cell biology

Science fiction blends science and story, but stories and images are among the building blocks of science itself to a greater extent than most people realize. The most engaging science books tackle the narratives that scientists believe and on which they base study designs and interpretations. Cells, Gels, and the Engines of Life provides a detailed case study of how such scientific stories and simple mental images operate to guide entire fields over decades – and not always along the best available paths.

With everything from bio-engineering to bio-hazards of keen interest in the popular and science-fictional imaginations, it is important to be clear on the fundamentals of how cells work. We might have thought we already knew, but this book questions a whole list of “textbook” fundamentals and offers an alternative, integrated framework for explaining a wide range of cell functions.

Once a misguided view has been established in any field, not only in economics, but apparently also even fields such as cell biology with relatively few obvious sources of political distortion, it can take a rare blend of courage, expertise, and clarity to budge things in a new direction. This can emerge not only in the storied times of Copernicus, Kepler and Galileo, but even today. It still takes a heroic protagonist to put it all together and say it out loud against layers of convention. Meet Dr. Gerald H. Pollack, the author, professor of bioengineering at the University of Washington.

A master class in scientific thinking

Anyone with a firm reading ability can delve into this book and might be surprised, given the school-inflicted association of basic science instruction with soporific textbooks, to be sucked in on the first page. This is much more than a book about how cells work; it is a master class in fresh and precise scientific thinking, an art much in need of renaissance in an age of truth by click-through count, research-grant total, and mere widespread assertion.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

J. Edgar, the new film directed by Clint Eastwood and starring Leonardo DiCaprio, is making the news for dealing frankly with the decades old rumors concerning Hoover’s private life. But that’s not what makes the film immensely valuable. Its finest contributions are its portrait of the psycho-pathologies of the powerful and its chronicle of the step-by-step rise of the American police state from the interwar years through the first Nixon term.

J. Edgar, the new film directed by Clint Eastwood and starring Leonardo DiCaprio, is making the news for dealing frankly with the decades old rumors concerning Hoover’s private life. But that’s not what makes the film immensely valuable. Its finest contributions are its portrait of the psycho-pathologies of the powerful and its chronicle of the step-by-step rise of the American police state from the interwar years through the first Nixon term.

The current generation might imagine that the egregious overreaching of the state in the name of security is something new, perhaps beginning after 9/11. The film shows that the roots stretch back to 1919, with Hoover’s position at the Justice Department’s Bureau of Investigation under attorney general A. Mitchell Palmer. Here we see the onset of the preconditions that made possible the American leviathan.

Palmer had been personally targeted in a series of bomb attacks launched by communist-anarchists who were pursuing vendettas for the government’s treatment of political dissidents during the first world war. These bombings unleashed the first great “red scare” in American history and furnished the pretext for a gigantic increase in federal power in the name of providing security. In a nationwide sweep, more than 60,000 people were targeted, 10,000 arrested, 3,500 were detained, and 556 people were deported. The Washington Post editorial page approved: “There is no time to waste on hairsplitting over infringement of liberties.”

Here we have the model for how the government grows. The government stirs up some extremists, who then respond, thereby providing the excuse the government needs for more gaining more power over everyone’s lives. The people in power use the language of security but what’s really going on here is all about the power, prestige, and ultimate safety of the governing elite, who rightly assume that they are ones in the cross hairs. Meanwhile, in the culture of fear that grips the country – fear of both public and private violence – official organs of opinion feel compelled to go along, while most everyone else remains quiet and lets it all happen.

The remarkable thing about the life of Hoover is his longevity in power at every step of the way. With every new frenzy, every shift in the political wind, every new high profile case, he was able to use the events of the day to successfully argue for eliminating the traditional limits on federal police power. One by one the limitations fell, allowing him to build his empire of spying, intimidation, and violence, regardless of who happened to be the president at the time.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

If you seek power over others, how much of an advantage does raw intelligence gain you?

If you seek power over others, how much of an advantage does raw intelligence gain you?

If you look at the makeup of the US Congress — which now has a 9% percent approval rating — or if you watch the Republican debates, you are not immediately inclined to label either the smart set. In fact, you have to be a dim bulb to repeatedly say many of the things that seem necessary for electability. On the other hand, a certain amount of cleverness is obviously necessary to outwit the media and your opponents.

Which is it? Two films that explore the relationship between power and brains are Being There (1979) and Limitless (2011). The films came out thirty years apart but deal with the same issues. Being There suggests that being dumb as a chicken is a huge advantage for those who seek political success. Limitless suggests that politics is the inevitable trajectory of a person who is far more intelligent than everyone else. Which is more realistic?

I’ll state my own view up front: politics is a gigantic waste of brains. If a person really has a gift for high-level thought, almost any profession would be a greater betterment to society and probably more self-fulfilling in the long run. Whereas it was probably once true that the political life attracted some of the best and brightest, it no longer seems true at all today.

Being There is both hilarious and serious, worth sitting down with at least once every few election seasons. Peter Sellers and Shirley MacLaine star in this adaptation of a novel by Jerzy Kosinski about an illiterate and simple-minded man named Chance who happened to be in the right place at the right time. His utterances are few and most concern what he has done his entire life, which has been to tend one garden on one estate and otherwise watch television.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

The Thing, a remake of a remake of a solid sci-fi/horror film directed by, despite what the credits may tell you, Howard Hawks, is being projected onto silver screens in dollar theaters across the country right now. While a viewing of the movie does not immediately make clear why theater space would be made available for such a project, I strongly suspect that in the current climate of more-CGI-less-story-less-character, none of the other reels delivered to theaters contained anything more promising. In other words, for about the same reason I occasionally find myself eating broccoli. The best thing I can say for it is that there were a handful of stretches, some of them two or three minutes in duration, in which I forgot how forgettable the movie was.

The Thing, a remake of a remake of a solid sci-fi/horror film directed by, despite what the credits may tell you, Howard Hawks, is being projected onto silver screens in dollar theaters across the country right now. While a viewing of the movie does not immediately make clear why theater space would be made available for such a project, I strongly suspect that in the current climate of more-CGI-less-story-less-character, none of the other reels delivered to theaters contained anything more promising. In other words, for about the same reason I occasionally find myself eating broccoli. The best thing I can say for it is that there were a handful of stretches, some of them two or three minutes in duration, in which I forgot how forgettable the movie was.

In this third generation version, a young, good-looking scientist is asked to come to Antarctica and given no clear reason why. She is only told that it is important. When she arrives, she discovers the scientists stationed there are excavating an alien spacecraft buried in the ice a hundred thousand years ago. They have found a creature, also buried in the ice, that they believe came along with the ship. It is nothing more than a blurry form under the translucent surface, and next to nothing about it has been discovered.

They dig out a block of ice containing the extraterrestrial but, because this is sci-fi/horror, it escapes and is so unfriendly that people start dying. The rest of the movie is a desperate fight to survive in the most inhospitable environment offered on this planet that still has breathable air. For those keeping track, yes, there is a black man in this movie. No, he doesn’t make it. And that’s not a spoiler, either. As soon as I reported the monster’s escape from its prison you knew no black man was going to live long enough to read the credits.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

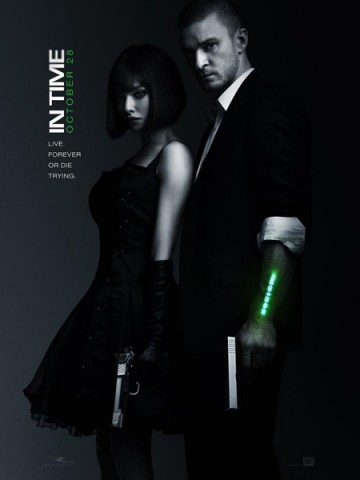

Before I studied Austrian Economics and profited from the clarity it brings to phenomena that otherwise seem chaotic and unfathomable, I read an article by Dave Barry that made me laugh. In it, he parodied the stock market, saying something to the effect of, “The DOW Jones plunged today when scientists discovered that Saturn had seven moons, and not six as previously thought.” That sentence encapsulated the mystifying and capricious vicissitudes of an economy I did not understand, much like airports stupefied the Cargo Cults. After watching In Time, it is obvious to me that writer/director/producer Andrew Niccol is mired in the same blithering ignorance that Mises and Rothbard pulled me out of.

Justin Timberlake plays Will Salas, a blue-collar man living day-to-day in a world where no one ages past 25 and time is the economy’s currency. The time you have left is measured on your forearm, and you can give and receive it either by placing your wrist over a scanner, for machine/human interactions, or gripping forearms with someone, for person-to-person transactions. The world is divided into time zones and people live in the one that pertains to their occupation and income level. As long as you have time on your forearm, you can live forever, but if you go broke, you die.

One night Will Salas saves a rich man who has wandered into Dayton, the poor time zone where Salas lives, from being robbed by so-called Minutemen, petty gangsters who steal people’s time. This man, Henry Hamilton, is 105 years old and weary of being alive. He bequeaths his century of time to Will and “times out,” but due to a surveillance camera that catches only part of the action, it looks to later observers that Will has murdered Henry. Meanwhile, on the very day her son becomes a rich man, Rachel Salas (Olivia Wilde) is caught in the middle of nowhere at night with, after making a loan payment, only ninety minutes left to live. The bus fare back home has been increased to two hours and the driver will not allow her on the bus without paying the full fare up front. None of the other passengers step forward to give her a small loan, so she is left to die. A grieving Will swears revenge on the system that killed his mother.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post