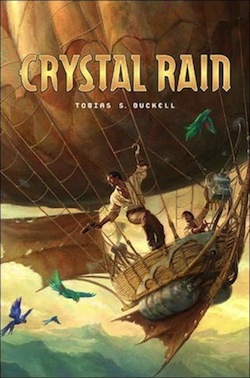

Steampunk is currently all the rage, but this book was published before steam engines and airships and whatnot became recently fashionable. And besides, Crystal Rain (Tor, 2007) is not your ordinary steampunk. It has a healthy dose of post-apocalyptic science fiction as well, but here too Crystal Rain breaks the mold. On the one hand, the setting includes sailboats and airships, gaslights, firearms, and, mostly in Capitol City, steam-powered trains, cars, and even a ship, and trolly-like electric cars. I don’t recall any conspicuous leather, aviation goggles, brass, or clockwork though. On the other hand, we quickly find out that this story takes place centuries after some cataclysmic disaster. There are near-mythical stories of the “old fathers,” and Preservationists seek to restore lost technologies. A barren area inland called Hope’s Loss causes people who travel through it to sicken and die. To add another twist, we quickly discover the story takes place not on Earth, but some distant planet, by the casual description of two moons in the sky and tales of the old fathers traveling to the land of Nanagada via “worm’s holes” and warming the planet with mirrors in the sky that have since crashed and burned. Turns out Nanagada is a lost colony planet. Caribbean-born author Tobias Buckell adds spice to the mix by populating the setting of his debut novel with a collection of mostly non-white races, dominated by Caribbean culture and dialect.

Actually, the first hints that you’re not reading the typical steampunk or post-apocalyptic novel come in the prologue when a mysterious black man with dreadlocks, dressed in top hat and trenchcoat, falls out of the sky in a “steaming metal boulder,” speaks gibberish to the natives for a minute, then after manipulating his throat suddenly speaks their language. He appears tired and thin, weak, so the natives take him back to their village — though he has strength left in him to kill a jaguar effortlessly with his bare hands on the way. After a week of pigging out, he’s all buffed out. All he tells them is that he’s looking for an old friend. This mysterious, superhuman figure we later find out to be Pepper, who features in several subsequent novels and short stories by Buckell. The author handles him well. Pepper has his limits, which are tested in the novel, and while he often appears to be a “looking out for #1,” cold-blooded mercenary-type, Buckell manages to give him a depth that defies expectations.

But the main protagonist of Crystal Rain is the man Pepper is looking for: John deBrun. John is a sailor, fisherman, and painter, with a hook in place of the left hand that he lost to frostbite on an ill-fated excursion to the icy north. He remembers nothing of his past from before he washed ashore 27 years prior in the town of Brungstun near the Wicked High Mountains that separate the Nanagadan Peninsula from the rest of the continent. But he has an uncanny ability to navigate, as if he has a GPS in his head. He has settled down there, married, and has a 13-year old son. Oh, and he doesn’t seem to have aged much in those 27 years.

Little do most know at the start, but the Azteca, who live on the other side of the Wicked Highs, are being driven by their bloodthirsty gods, the Teotl, to cross the mountains and invade Nanagada. Another main viewpoint character, Oaxyctl (O-ash-k-tul), who is actually an Aztecan double agent spying for the Nanagadans, has the bad luck to be accosted by one if his gods and tasked with tracking down John deBrun and delivering him to it or else Oaxyctl’s life will be forfeit. The Teotl needs John alive because it believes he alone possesses secret codes to unlock the Ma Wi Jung. Whatever that is. (Heh. Is John “The Chosen One”?) Oaxyctl is placed in an impossible position: mortally afraid of his gods, still fundamentally an Aztecan despite working for the Nanagadans, he later comes to like John, whom he rescues from an Aztecan war party’s sacrificial altar after John had been separated from his family and captured. Buckell keeps us wondering when, or if, Oaxyctl will betray John’s trust.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post