Prometheus Unbound has been on unannounced hiatus for a while now. We’ve all been rather busy with work and family and other projects. But I will be reviving it and the podcast. Reviving the site and keeping it going will of course be easier if we have more contributors, so if you’re interested in publishing news, reviews, articles, interviews, and the like on Prometheus Unbound, please contact me.

The main subject of this post, however, is one of the other projects that has been occupying my attention. I recently launched, in November 2013, the Libertarian Fiction Authors Association.

If you’re like me, you enjoy reading fiction but have a difficult time finding stories that truly reflect your values and interests. This discovery problem affects everyone, but is particularly acute for niche markets like ours. There are individuals and organizations (including Amazon) attempting to solve the problem for authors and readers in general, but no one was really catering to libertarians specifically. Even Prometheus Unbound cannot provide the solution: it’s primarily about providing a libertarian perspective on the fiction that interests us, particularly science fiction and fantasy, much of which is not produced by libertarians.

How many libertarians out there have published fiction? How many more are aspiring authors, who are either writing their first novel or are thinking about it but need some encouragement and guidance? I had no idea, but I was sure there were far more than I knew about personally.

As an activist, I also think that dramatizing our values through fiction is an important way to spread the message of liberty.

As an aspiring fiction author myself, I wanted to form a group made up of fellow libertarian writers who could learn from, encourage, and push each other to accomplish their goals and continually reach for new heights — and, eventually, to get my stories into the hands of new readers.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

Anyone who read Dr. Seuss’s The Lorax as a kid might dread the movie version. No one really needs another moralizing, hectoring lecture from environmentalists on the need to save the trees from extinction, especially since that once-fashionable cause seems ridiculously overwrought today. There is no shortage of trees and this is due not to nationalization so much as the privatization and cultivation of forest land.

And yet, even so, the movie is stunning and beautiful in every way, with a message that taps into something important, something with economic and political relevance for us today. In fact, the movie improves on the book with the important addition of “Thneed-Ville,” a community of people who live in a completely artificial world lorded over by a mayor who also owns the monopoly on oxygen.

This complicates the relatively simple narrative of the book, which offers a story of a depleted environment that doesn’t actually make much sense. The original posits an entrepreneur who discovers that he can make a “Thneed” — a kind of all-purpose cloth — out of the tufts of the “Truffula Tree,” and that this product is highly marketable.

Now, in real life, any capitalist in this setting would know exactly what to do: immediately get to work planting and cultivating more Truffula trees. This is essential capital that makes the business possible and sustainable through time. You want more rather than less capital. An egg producer doesn’t kill his chickens; he breeds more. But in the book (and the movie), the capitalist does the opposite. He cuts down all the trees and, surprise, his business goes bust.

The book ends with the aging capitalist regretting his life and passing on the last Truffula seed to the next generation. The end. However, the movie introduces us to the town that is founded after this depletion occurs. It is shielded off from the poisoned and depleted world outside, and oxygen is pumped in by the mayor who holds the monopoly on air and builds Lenin-like statues to himself. The people eventually rise up when they discover that “air is free” and thereby overthrow the despot, chopping off the statue’s head.

It was this line about how air is free that clued me in to the movie’s possible subtext. You only need to add one metaphor to see how this movie can be the most important and relevant political-economic drama of the season.

The metaphorical substitution is this: The Trees are Ideas.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

If you like your fantasy gritty, violent, personal, and character-driven, featuring flawed antiheroes, then you’ll want to listen to these two fascinating three-part series of podcast episodes on SF Signal.

Hosted and moderated by Patrick Hester and Jaym Gates, the panels include noted authors, editors, and artists, such as Lou Anders, Scott Lynch, James Enge, Saladin Ahmed, John Picacio, and many more.

The discussions are wide ranging: The panelists discuss what makes a story sword & sorcery (do you agree with Lou?), the proper length of a sword & sorcery story in prose form, and what the boundaries between sword & sorcery, sword & planet stories (Edgar Rice Burroughs’s John Carter), epic fantasy, and urban fantasy are. They talk about the new sword & sorcery (by authors Scott Lynch, Joe Abercrombie, James Enge, Michael Chabon, and others) in relation to its progenitors in the classic pulps (Robert E. Howard, Fritz Leiber) and the more mature work of Michael Moorcock, the proliferation of sword & sorcery into non-Western settings (e.g., sword & sandal stories by Saladin Ahmed and Howard Andrew Jones), and sword & sorcery in different mediums, such as film (Conan), table-top roleplaying games (D&D), contemporary video games (Skyrim), and art (Boris Vallejo).

After listening to all of these episodes, what’s your take on sword & sorcery?

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

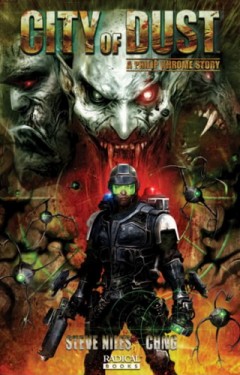

Brilliant art coupled with a clever story make Steve Niles’s graphic novel City of Dust an instant sci-fi horror classic. Niles, who also wrote graphic novel 30 Days of Night and the first draft of its film adaptation, loops good cops, bad laws, prostitutes, and mechanical nightmares into a deeper story about imagination and thought crimes. The story takes place within a metropolis setting where your socio-economic status, as well as your physical safety, is dependent on how many stories you are above the ground. Cops roam the lower parts of this vertical city looking for looking for anything resembling imagination-paraphernalia, classified as anything that might evoke imaginative thinking or thought crimes. All media is banned in the year 2166: books, music, movies, religious art, even religion itself.

Khrome, leading character and cop convinced something is wrong with the system, was persuaded as a child to have his father arrested and imprisoned for life simply for reading him children’s books. Years later Khrome does the arresting and the trials are conducted instantly via e-mail. The verdict for indulging in such imagination-paraphernalia…instant death. Later on in the story, Khrome becomes involved in a crime scene investigation where a children’s book is found on the scene of a mutilated, half-eaten corpse. Told to keep his distance until the fed’s arrival, Khrome can’t help but open this rectangular object and indulge. His actions are cause for alarm and Khrome finds himself involved in much more than police work.

Overall, City of Dust is your typical dark, sinister sci-fi horror graphic novel (though nothing close to the level of disturbia in Garth Ennis’ Crossed). It’s well-written and well-drawn with lots of political undertones dealing with authoritarianism and censorship, though the story feels slightly rushed at the end. The author’s well-structured plot seems to fall apart in a last minute sprint to finish the project within the remaining 10 pages of the book.

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post