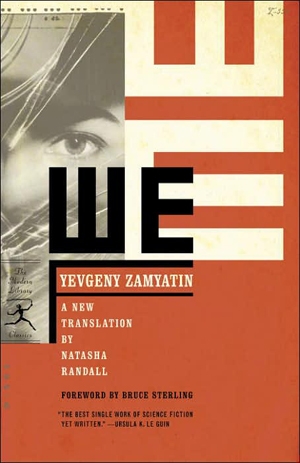

In this episode of the Libertarian Tradition podcast series, part of the Mises Institute’s online media library, Jeff Riggenbach makes the case that Yevgeny Zamyatin’s dystopian science fiction novel, We, belongs in the libertarian tradition.

You can also read the transcript below:

When we think of the libertarian tradition, we tend naturally to think of political philosophers and economists of the past. But surely one part of the libertarian tradition belongs to novelists and other fiction writers.

In earlier podcasts in this series, I’ve already discussed two such figures: Ayn Rand, whose 1957 novel, Atlas Shrugged, is, arguably, one of the half-dozen most important libertarian works of the 20th century, and John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, the professor of philology at Oxford whose giant fantasy novel, The Lord of the Rings, published just a few years before Atlas Shrugged, is arguably the most culturally influential single novel published in English in the 20th century.

This week, I’d like to talk about a writer whose level of influence has been much more modest, but whose indirect influence has nevertheless been considerable. Regular listeners to this series know what I mean by indirect influence. I gave an example of it just last week, when I discussed the life and career of Isabel Paterson. Paterson’s libertarian classic, The God of the Machine, has never reached a wide readership, but, thanks to the effort of her protégé, Ayn Rand, Paterson herself has influenced millions of readers who have never even seen a copy of The God of the Machine.

The writer I’m talking about today wrote a novel in which a citizen of a totalitarian state of the future meets a woman and becomes obsessed with her. He begins a forbidden sexual affair with this woman, meeting with her illicitly in a very old part of the city where the intrusive gaze of the all-encompassing government doesn’t seem to penetrate. Through his relationship with her, he becomes involved in the organized underground opposition to the all-encompassing government — an opposition he had never previously realized existed at all. Ultimately, he and the woman are caught, imprisoned, and tortured. In the end, he is sincerely repentant of his crimes and is completely devoted to the all-encompassing government that has done him all this harm.

A familiar story, no? Can you tell me what novel I’ve just described? Ah, I see a hand in the back of the room. Yes? “George Orwell’s 1984,” you cry out confidently. And your answer is correct, but only as far as it goes, which is, perhaps, not quite as far as you thought it would.

That is a description of the plot of 1984, which was published, as we all know, in 1949. But Orwell adapted the plot of 1984 from another novel, one originally published 25 years earlier in 1924. That earlier novel was entitled, simply, We. It was the work of a not-very-well-known Russian writer, Yevgeny Zamyatin. Zamyatin was not very well known outside Russia when We was first published, and he was still not very well known in the West 25 years later, when Orwell published 1984. He remains not very well known in the West to this day.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post