Logic is never kind to a story about time travel. It seems that no matter what idea or aspect of so-called fourth dimensional travel a storyteller wishes to pursue, something does not work right — contradictions abound. The biggest plot holes in the history of fiction are to be found therein. For my money, this is the first and best reason to suppose that time travel is not possible. Reality is nothing if not possible and plausible — at least from the perspective of one in possession of the relevant facts — and if a story cannot be made to work right when time travel is involved, reality probably cannot either.

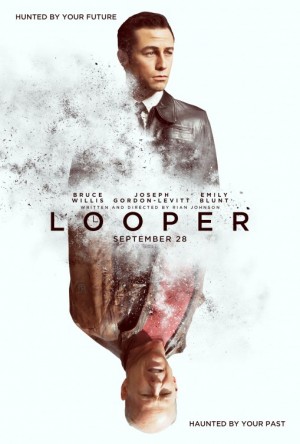

There is, however, a lot of potential in such tales. If a viewer will but suspend his disbelief and allow an author or filmmaker to explore one possibility while forgetting its necessary and contradictory corollaries, then some interesting possibilities may be realized. Rian Johnson has done a first-rate job of spinning a time-traveling yarn with the new movie Looper, if the audience will afford it such consideration.

The year is 2044, and time travel, as we are told by the narrator and protagonist (played by Joseph Gordon-Levitt), is not yet invented. Thirty years in the future, it is/will be (it occurs to me that we need another tense or two in the English language when we discuss these things). It is illegal, though, and only mobsters make use of it, to send back their targets to be eliminated and their bodies disposed of. The men who do the eliminating and disposing are called loopers, and they earn that appellation when they close their own loop by, at the end of their contract, killing their 30-years-older selves.

Our protagonist, called simply Joe, is a drug abusing, well-dressed looper with a manner perhaps a bit too refined, and a face perhaps too smooth and handsome, for someone in his station. Leonardo DiCaprio, in The Departed, managed to overcome his golden beauty and give a convincing portrayal of a hoodlum. I would have preferred something rougher like that in Looper. Gordon-Levitt has all the makings of a leading man, but I thought the role he portrayed in this film was not quite the right one.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

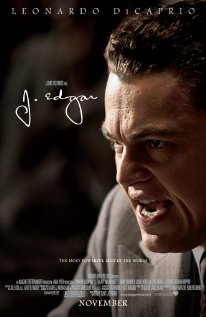

J. Edgar, the new film directed by Clint Eastwood and starring Leonardo DiCaprio, is making the news for dealing frankly with the decades old rumors concerning Hoover’s private life. But that’s not what makes the film immensely valuable. Its finest contributions are its portrait of the psycho-pathologies of the powerful and its chronicle of the step-by-step rise of the American police state from the interwar years through the first Nixon term.

J. Edgar, the new film directed by Clint Eastwood and starring Leonardo DiCaprio, is making the news for dealing frankly with the decades old rumors concerning Hoover’s private life. But that’s not what makes the film immensely valuable. Its finest contributions are its portrait of the psycho-pathologies of the powerful and its chronicle of the step-by-step rise of the American police state from the interwar years through the first Nixon term.

The current generation might imagine that the egregious overreaching of the state in the name of security is something new, perhaps beginning after 9/11. The film shows that the roots stretch back to 1919, with Hoover’s position at the Justice Department’s Bureau of Investigation under attorney general A. Mitchell Palmer. Here we see the onset of the preconditions that made possible the American leviathan.

Palmer had been personally targeted in a series of bomb attacks launched by communist-anarchists who were pursuing vendettas for the government’s treatment of political dissidents during the first world war. These bombings unleashed the first great “red scare” in American history and furnished the pretext for a gigantic increase in federal power in the name of providing security. In a nationwide sweep, more than 60,000 people were targeted, 10,000 arrested, 3,500 were detained, and 556 people were deported. The Washington Post editorial page approved: “There is no time to waste on hairsplitting over infringement of liberties.”

Here we have the model for how the government grows. The government stirs up some extremists, who then respond, thereby providing the excuse the government needs for more gaining more power over everyone’s lives. The people in power use the language of security but what’s really going on here is all about the power, prestige, and ultimate safety of the governing elite, who rightly assume that they are ones in the cross hairs. Meanwhile, in the culture of fear that grips the country – fear of both public and private violence – official organs of opinion feel compelled to go along, while most everyone else remains quiet and lets it all happen.

The remarkable thing about the life of Hoover is his longevity in power at every step of the way. With every new frenzy, every shift in the political wind, every new high profile case, he was able to use the events of the day to successfully argue for eliminating the traditional limits on federal police power. One by one the limitations fell, allowing him to build his empire of spying, intimidation, and violence, regardless of who happened to be the president at the time.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post