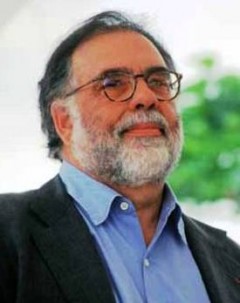

In an interview with The 99% — Francis Ford Coppola: On Risk, Money, Craft & Collaboration — Coppola offers some very insightful and sensible remarks about creativity, copyright, the role of copying and imitation in the development of art and an artist’s own voice, the business of the arts, and immortality. As Cory Doctorow writes: “It’s always great to learn about seasoned, accomplished artists who refuse the lure of reactionary, knee-jerk get-off-my-lawnery.”

I once found a little excerpt from Balzac. He speaks about a young writer who stole some of his prose. The thing that almost made me weep, he said, “I was so happy when this young person took from me.” Because that’s what we want. We want you to take from us. We want you, at first, to steal from us, because you can’t steal. You will take what we give you and you will put it in your own voice and that’s how you will find your voice.And that’s how you begin. And then one day someone will steal from you. And Balzac said that in his book: It makes me so happy because it makes me immortal because I know that 200 years from now there will be people doing things that somehow I am part of. So the answer to your question is: Don’t worry about whether it’s appropriate to borrow or to take or do something like someone you admire because that’s only the first step and you have to take the first step…

You have to remember that it’s only a few hundred years, if that much, that artists are working with money. Artists never got money. Artists had a patron, either the leader of the state or the duke of Weimar or somewhere, or the church, the pope. Or they had another job. I have another job. I make films. No one tells me what to do. But I make the money in the wine industry. You work another job and get up at five in the morning and write your script.

This idea of Metallica or some rock n’ roll singer being rich, that’s not necessarily going to happen anymore. Because, as we enter into a new age, maybe art will be free. Maybe the students are right. They should be able to download music and movies. I’m going to be shot for saying this. But who said art has to cost money? And therefore, who says artists have to make money?

(Image: Coppola Francis Ford at Cannes in 2001, Ed Fitzgerald/Wikimedia Commons)

[Via C4SIF and Boing Boing.]