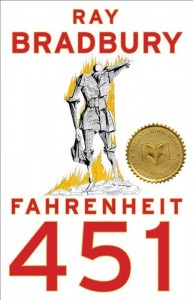

In light of Ray Bradbury’s recent passing, it may be apropos to revisit an old episode of Jeff Riggenbach’s Libertarian Tradition podcast from 2010 in which he discusses why we should revisit Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 45.

You can also read the transcript below:

Ray Bradbury celebrated his 90th birthday this past Sunday. He was born August 22, 1920 in Waukegan, Illinois, a medium-sized town of around 20,000 people about midway between Chicago and Milwaukee on the western shore of Lake Michigan. Bradbury has depicted Waukegan fondly, even idyllically, in his fiction, most notably in his 1957 novel Dandelion Wine — even though the Waukegan conjured up in that book, which is set in 1928, is a bit larger than the Waukegan Bradbury was born into in 1920. The town’s population grew by more than 50 percent during the ’20s. By the beginning of the Great Depression, there were more than 33,000 people who called Waukegan home. The Bradbury family was not to be among these people for much longer, however.

They had already spent a year in Tucson, Arizona in the ’20s, for reasons having to do with Ray’s father’s employment. Tucson was where Ray attended first grade. And in school year 1932/33, when Ray was 12, they were back in Tucson again. Then, after a few months cleaning up loose ends in Waukegan, not long before Ray’s 14th birthday, they moved to Los Angeles, where they remained. Ray Bradbury himself is there to this day. It was in Los Angeles that he went through high school and in Los Angeles that he launched his extremely successful career as a fiction writer.

It is common to hear Ray Bradbury described as a “science-fiction writer,” but this is misleading at best. Only a minority of Bradbury’s total production is science fiction by any normal standard, and at least half of it is straightforward realistic fiction like Dandelion Wine. The fact is, however, that Bradbury’s second, third, and fourth books, his first three books to come to widespread attention —The Martian Chronicles (1950), The Illustrated Man (1951), and Fahrenheit 451 (1953) — were works of science fiction, or, at least, were widely believed to be. Bradbury was typecast early, you might say. He came to fame as a “science-fiction writer,” and a “science-fiction writer” he will therefore forever remain.

For our purposes here, on the other hand, Bradbury’s most important book is undeniably the third of those titles I just listed: Fahrenheit 451, his short novel about censorship, one of the most influential libertarian novels of the 20th century, first published nearly 60 years ago. And of all Ray Bradbury’s books, Fahrenheit 451 is probably the one most entitled to be called “science fiction.”

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post