In a recent addition to The Libertarian Tradition podcast series, part of the Mises Institute’s online media library, Jeff Riggenbach discusses Friedrich Hayek and American Science Fiction.

You can also read the transcript, which was later published as a Mises Daily article.

In the podcast, Riggenbach discusses the dramatization of Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek’s ideas in William Gibson’s novel Pattern Recognition and Alfred Bester’s short story “Time is the Traitor.”

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

When I wasn’t paying attention Jeff Riggenbach did two more audio podcasts on libertarianism and science fiction in his series for the Mises Institute, The Libertarian Tradition. Here is one, a followup on the previous podcast on libertarian science fiction.

You can also read the transcript, which was later published as a Mises Daily article: “Some Further Notes on Libertarian Science Fiction.”

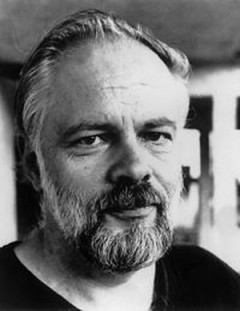

In the podcast, Riggenbach discusses Anthony Burgess’s novel A Clockwork Orange and several novels by Philip K. Dick (including The Man in the High Castle, which our own Matthew Alexander recently reviewed) as well as two nonfiction books.

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

Author Philip K. Dick

It seems to me that of the two most important elements of a story, plot and character, plot seems to be more masculine and character more feminine. That is to say, a story for men, if it skimps on either of the two, is more likely to skimp on character, while a story for women will shortchange the plot. The best stories, of course, are strong in both categories. Science fiction, being a more masculine genre — in fact the only genre of fiction whose readership is more male than female — has traditionally been solid on plot and hit or miss with the characters. There are exceptions, as one would expect, and Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, a Hugo Award winner, is one of these.

The story takes place in what was the present day when the novel was written, 1962, but in an alternate timeline where Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan won World War II. The United States has been carved into puppet governments; Germany has sent astronauts to Mars, drained the Mediterranean for farmland and committed multiple genocides; Japan controls the west coast of North America, having become a cultural as well as political hegemon.

It is a marvelous setting, both in conception and in description. Dick’s prose makes it come alive with a few deft touches here and there, sparse but effective. Whereas in most stories the setting serves as a place for the plot to take place, the reader here gets the sense that the plot is just something to have happen in the setting. The world and its characters are the point; what they do in the narrative has less importance.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

Finalists for the 2011 Prometheus Award for best libertarian novel were announced just yesterday. One finalist, Ceres, by past award-winner L. Neil Smith, has already been reviewed on Prometheus Unbound. Also making the cut is Cory Doctorow’s For The Win. I have a copy of this novel and plan to review it soon, after I publish a few overdue reviews.

As a reminder to our readers, we are open to submissions of reviews (as well as news, articles, interviews). Even if you can’t contribute regularly, we’d like to have a number of part-timers on our staff who only contribute occasionally. We’re even open to one-time contributors.

So if you’d like to read and review one of the other Prometheus Award finalists, nominees, past winners, or another piece of fiction, we’d be happy to consider it for publication.

Below is the full press release from the Libertarian Futurist Society, which presents the Prometheus Award:

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

Good things come to those who wait, the old adage goes, and the world has waited a century for Mark Twain’s autobiography, which, in Twain’s words, is a “complete and purposed jumble.” But this 760 page jumble is a good thing. And well worth the wait.

Twain, or Samuel L. Clemens, compiled this autobiography over the course of 35 years. The manuscript began in fits and starts. Twain, while establishing his legacy as a beloved humorist and man of letters, dashed off brief episodes here and there, assigning chapter numbers to some and simply shelving others. In 1906, he began making efforts to turn these cobbled-together passages into a coherent narrative. He even met daily with a stenographer to dictate various reflections and then to compile them into a single, albeit muddled, document. The result was a 5,000 page, unedited stack of papers that, per Twain’s strict handwritten instructions, could not be published until 100 years after his death.

Twain, or Samuel L. Clemens, compiled this autobiography over the course of 35 years. The manuscript began in fits and starts. Twain, while establishing his legacy as a beloved humorist and man of letters, dashed off brief episodes here and there, assigning chapter numbers to some and simply shelving others. In 1906, he began making efforts to turn these cobbled-together passages into a coherent narrative. He even met daily with a stenographer to dictate various reflections and then to compile them into a single, albeit muddled, document. The result was a 5,000 page, unedited stack of papers that, per Twain’s strict handwritten instructions, could not be published until 100 years after his death.

To say that we’ve waited a century to view this manuscript is only partially accurate because pieces of the manuscript appeared in 1924, 1940, and 1959. But this edition, handsomely bound by the University of California Press, and edited by Harriet Elinor Smith and others of the Mark Twain Project, is the first full compilation of the autobiographical dictations and extracts to reach print. The editors, noting that “the goal of the present edition [is] to publish the complete text as nearly as possible in the way Mark Twain intended it to be published before his death,” explain that “no text of the Autobiography so far published is even remotely complete, much less completely authorial.” The contents of this much-awaited beast of a book, then, are virtually priceless, and no doubt many of the previously unread or unconsidered Twain passages will become part of the American canon.

Stark photographs of the manuscript drafts and of Twain and his subjects — including family members and residences — accompany this fragmentary work. The lively and at times comical prose is in keeping with the rambling style of this rambling man whom readers have come to know and appreciate for generations. Would we have expected any less?

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

Cory Doctorow’s Little Brother is a tale about tech-savvy teenagers as they rebel against a Department of Homeland Security crackdown following a terrorist attack on San Fransisco. A piece of YA fiction that even adults can enjoy — it’s YA largely because of its teenage protagonists and its educational aim at young people — Little Brother is the 2009 Prometheus Award winner for best libertarian novel. Little Brother also won the John W. Campbell Memorial Award and was a finalist for the Hugo Award.

Little Brother is set entirely in San Fransisco, California, in the very near future. Much of the technology in the story is already available, and what is not can easily be conceived as being on the horizon. The story is told entirely in the first person, from the point of view of the main character, Marcus Yallow. Marcus at first goes by the handle w1n5t0n (Winston in leetspeak, a homage to George Orwell’s 1984, as is the title of the book) but later switches to M1k3y (which could be a reference to the computer Mike in Robert Heinlein’s The Moon is a Harsh Mistress).

As the story opens, we are introduced to Marcus and three of his friends — Jolu (Jose Luis), Van (Vanessa), and best friend, Darryl — who ditch school to play an ARG (Alternate Reality Game) called Harajuku Fun Madness in and around the city. They happen to have the misfortune of being in the wrong part of town when terrorists blow up the Bay Bridge. In the chaos and confusion that follows, they get picked up by the Department of Homeland Security and then subjected to several days of interrogation and psychological torture in a “Gitmo by the Bay” before being released (with the exception of Darryl) with threats to keep quiet about their experience…or else. But once set free, Marcus and his friends are disturbed to see their city being turned into a police state.

Marcus resolves to fight back against the DHS, to restore civil rights and liberties and to free Darryl. He soon becomes the unofficial leader of a growing, decentralized movement of rebellious teenagers. But his covert struggle starts to put a strain on his relationships with his family and friends.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

Aaron Eckhart plays SSgt. Michael Nantz

One way to determine just how predisposed one is to sci-fi is by comparing one’s opinion of Battle: Los Angeles with one’s opinion of Black Hawk Down. This opportunity is now available to theater-goers because the former movie was made by taking the old reels of the latter movie and digitally inserting aliens. This of course is not literally true (though it gives the good reader a very good idea of what to expect should he purchase tickets) so it’s not a perfect test. Black Hawk Down, as I recall, had some directorial flourishes and humorous moments that were absent from its sci-fi version, while the sci-fi version manages to pull more of a plot together amid all those bullets and explosions (indeed, I remember thinking, after Black Hawk Down, that the moviemakers had saved some money on production by bypassing the screenwriter at the cost of a missed opportunity to make a good movie). These variables aside, the two flicks are remarkably similar and one may take the test at theaters over the next handful of weeks.

For me, adding aliens to the plot, such as it is, went some way towards making the movie a more enjoyable experience. This should not be misconstrued as an endorsement for the movie with no reservations, merely a preference for one military action demo reel over another. As Shakespeare wrote, “If two men ride of a horse, one must ride behind.” If I am going to sit through about 100 minutes of violence and destruction by way of an armed forces recruitment video, there at least ought to be an alien invasion.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post