My name is Geoffrey Allan Plauché. I’m a philosopher and an academic. I decided to launch a libertarian review of fiction and literature as a sort of online “magazine” because I’m not aware of any other such site and I think there is a need for one.

The closest things I can think of to Prometheus Unbound are the quarterly newsletter of the Libertarian Futurist Society, similarly titled Prometheus, and a new blog called Austrian Economics and Literature. The former is print-bound and focused almost exclusively on science fiction, the latter online but narrowly focused on — you guessed it — Austrian Economics and literature. I’m glad these publications exist but, taken individually and even together, they’re not exactly what I’m looking for.

Prometheus Unbound will be entirely online. I think print-only is a dead and antiquated medium, particularly for a small niche publication with a heavy emphasis on science fiction (the literature of the future and change,1 science and technology) and catering to libertarians. We can publish more frequently online, in more discrete chunks, for less money, and reach far more people in a variety of ways (the website, myriad rss feeds, email, Google+, Twitter, Facebook, and the like).

Prometheus Unbound will have a broader scope. Not simply Austrian Economics but libertarianism, albeit a libertarianism informed by Austrian Economics. Not simply literature but also popular fiction that does not (yet) qualify for that high distinction in the eyes of literary critics or the masses. Not simply science fiction but also fantasy and other genres, but still primarily science fiction and fantasy (as they are my primary interest). Not just prose but, probably to a lesser degree, other media as well — such as film, tv, comics and graphic novels, poetry, and games. Our focus will not be on libertarian fiction (though we are on the lookout for it) or fiction by libertarian authors (who are distressingly too few in number) but on reviewing and commenting on fiction from a libertarian perspective.

As I said, I plan to build Prometheus Unbound into something like an online magazine. I hope this will not be a one-man show. We will feature news, reviews, editorials and other commentary, non-fiction articles, eventually interviews (I hope), and, in the undetermined future, possibly some original fiction. I’m looking for fellow libertarians, particularly fans of science fiction and fantasy, who would be interested in contributing on either a regular or an irregular basis. We’re in need of editors, regular writers or columnists, and irregular or part-time contributors. Even if you only contribute a few reviews a year on your own schedule or lack thereof, we’d be happy to consider your submissions.

If you’re interested in becoming a regular or part-time contributor, you can send a submission query or contact me about a position via the Contact form. See the About and Submissions pages for more information.

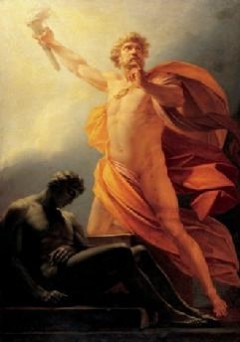

Finally, a few words about why I chose the title Prometheus Unbound: I took inspiration from Percy Bysshe Shelley’s closet drama, a play not intended for the stage, of the same name. There also happens to be an episode of the science fantasy tv series Stargate SG-1 with the same title as well as a seminal book of economic history titled The Unbound Prometheus. The latter, by David S. Landes, was influential for labeling the Second Industrial Revolution, which was also known as the Technological Revolution for its abundance of innovations and inventions that drove modernization and technological development in Western Europe beginning in the mid-1800s.

Finally, a few words about why I chose the title Prometheus Unbound: I took inspiration from Percy Bysshe Shelley’s closet drama, a play not intended for the stage, of the same name. There also happens to be an episode of the science fantasy tv series Stargate SG-1 with the same title as well as a seminal book of economic history titled The Unbound Prometheus. The latter, by David S. Landes, was influential for labeling the Second Industrial Revolution, which was also known as the Technological Revolution for its abundance of innovations and inventions that drove modernization and technological development in Western Europe beginning in the mid-1800s.

While Landes’s book tells the economic-historical story of the results of relatively unchained minds — unprecedented progress and prosperity — Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound dramatizes a related political message in mytho-poetic form. Shelley’s play was inspired by the Greek tragedian Aeschylus’s own telling of the myth of the Titan punished by Zeus for “stealing”2 fire from the gods and giving it to Man. But whereas Aeschylus had oppressor and victim reconcile, Shelley thought such an ending to be unfitting:

But, in truth, I was averse from a catastrophe so feeble as that of reconciling the Champion with the Oppressor of mankind. The moral interest of the fable, which is so powerfully sustained by the sufferings and endurance of Prometheus, would be annihilated if we could conceive of him as unsaying his high language and quailing before his successful and perfidious adversary.

Instead of reconciliation, Shelley gives us a revolution “championing free will, goodness, hope and idealism in the face of oppression.” Zeus (Jupiter) is overthrown and Prometheus is thereby freed. But rather than replace one tyrant with another, as so often happens with revolutions, particularly exemplified by the recent (at the time) French Revolution, the play ends with no one in political power at all — an anarchist’s paradise.

On the importance of dramatizing our values (pdf), Shelley ends the preface to his play:

My purpose has hitherto been simply to familiarize the highly refined imagination of the more select classes of poetical readers with beautiful idealisms of moral excellence; aware that, until the mind can love, and admire, and trust, and hope, and endure, reasoned principles of moral conduct are seeds cast upon the highway of life which the unconscious passenger tramples into dust, although they would bear the harvest of his happiness.

Fiction plays important roles in our lives and I think it is an important medium for expressing libertarian values. Our Prometheus Unbound will aim to identify libertarian values dramatized in works of fiction and literature and to bring works that contain those values to the attention of our readers. But I also hope that by doing so Prometheus Unbound will help promote the inclusion of libertarian values in more published fiction.

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post