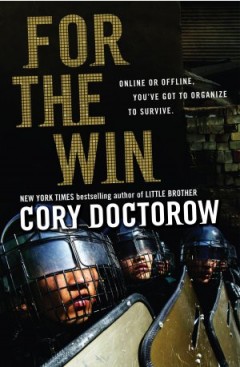

Cory Doctorow’s latest YA novel, For The Win, just might be the Jungle of the digital age — a depiction of the plight of professional gamers and their struggle to unionize and extract concessions such as better pay, shorter hours, and safer working conditions (?!) from their employers through collective bargaining. Not being an avid gamer myself, much less a professional gold farmer, I’m left to wonder if it is as poorly researched and inaccurate as Upton Sinclair’s piece of socialist propaganda fiction. I expect left-libertarians will tend to like this novel but other libertarians will not. As for myself, I struggled to finish it and do not recommend it — as much because of the writing style and quality of writing as the subject matter.

For The Win opens with a gifted Chinese gold farmer — a working gamer who plays to collect game money and items to sell for “real” money to “rich,” lazy, mostly American gamers — in China who just happens to have the Western name of Matthew. He’s attempting to strike out on his own but is visited by Boss Wing’s goons and taught a lesson. Then we meet an American Jew in Los Angeles who goes by the Chinese name of Wei-Dong and moonlights, against his parents’ orders, as a gold farmer with some online buddies in China. Next, we’re introduced to Mala, aka General Robotwallah, a poor Indian girl with a talent for strategy and leadership, who is hired by a mysterious man to use her “army” to harass gold farmers in-game because they allegedly disrupt the game for honest, paying customers.

Before long we’re introduced to Big Sister Nor, a mysterious new figure on the scene who is out to organize working gamers into a union to fight corruption and improve their circumstances. As the novel progresses, we’re introduced to more characters, mostly in China and India, where the bulk of the action takes place. Perhaps the most notable is a female Chinese underground radio host who caters to the factory girls, giving them advice and urging them to stand up for themselves, while she dodges police raids, moving from safe house to safe house under a series of false identities.

One of the themes of the novel is how difficult it has been historically for workers to organize and how the internet (including social media and online games) provide game-changing tools for organizing labor. There is much truth to this, though I am skeptical that even the myriad tools of the internet can allow a voluntary global union to pull off anything like the ambitious scheme Cory’s protagonists endeavor to carry out in the novel. Although Cory has characters voice the usual skeptical objections to the efficacy of a voluntary global union, I don’t think he adequately addresses the difficulties such a union would face even in the digital age. Without state-backed coercion (directed at businesses, scabs, and their own members), how much power would a union really have, particularly spread out over the globe? Sure, gamers have an advantage in that they all work virtually in the same place — but still…

To Cory’s credit, however, he does depict a truly voluntary union whose leaders welcome freely competing unions in the market. The International Workers of the World Wide Web (IWWWW) or Webblies, as they call themselves,1 even eschew a formal hierarchy. The de facto head of the union at one point exclaims to her followers, “I’m not magic. … You all lead yourselves.” They also, admirably, do not seek compliance with their demands through legislation or regulation. Instead, they engage in self-help. Libertarians may find some of their methods questionable, however.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

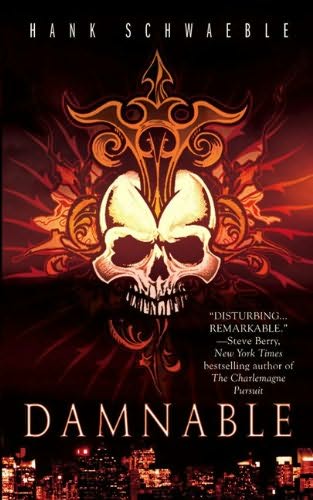

Diabolical, by Hank Schwaeble, is a Jake Hatcher novel, the sequel to Damnable. It takes place a short time after the events of the first novel, but in a new location. Many of the same characters are back, with a few new ones, and the recipe for the story makes use of the same ingredients in just about the same proportions. How you felt about the first book is, within a reasonable margin, how you are going to feel about its sequel.

Diabolical, by Hank Schwaeble, is a Jake Hatcher novel, the sequel to Damnable. It takes place a short time after the events of the first novel, but in a new location. Many of the same characters are back, with a few new ones, and the recipe for the story makes use of the same ingredients in just about the same proportions. How you felt about the first book is, within a reasonable margin, how you are going to feel about its sequel.

Steven Soderbergh

Steven Soderbergh