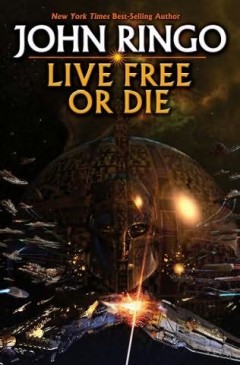

In 2010, John Ringo published the first book of the Troy Rising trilogy. Titled Live Free or Die, it is a story on a grand scale, a great symphony of a book but by an author who probably should stick to bagatelles. Though it started well and had my interest, it was a chore to get through most of it. There was enough creativity and verve for a short story, but by the end these had faded and I was glad to be finished.

It is the kind of story I imagine Ted Nugent would enjoy reading. Filled with gun-toting, rugged individuals who thrive on infuriating the Thought Police and composing odes to capitalism, the book might almost seem libertarian until one realizes just how besotted with militarism and American exceptionalism the author is. I have no problem with a man a bit rough around the edges, a touch short on couth and decorum, but Ringo at times goes beyond that into deliberate callousness, especially as regards sex and race.

There are many sensitive liberals who both need and deserve a little rattling from time to time, if only for our amusement, but there are just as many conservatives who could use a dose of circumspection, introspection, and nuance. I am tempted to suggest we lock Ringo in a room with his diametric opposites, to see if there might be a mutually beneficial rubbing off, but I am afraid someone would end up dying.

Live Free or Die begins with an alien race that establishes a portal in our solar system. They have no goals except to neutrally manage the portal, but the next race that appears is bent on imperial control of Earth. They begin by destroying some major cities and then demanding tribute. Though this species, the Horvath, is technologically backwards in comparison to other civilizations in the galaxy, they are yet far ahead of humans.