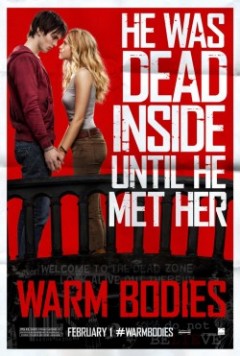

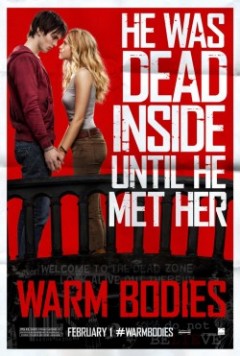

Warm Bodies, based on a novel by Isaac Marion that I haven’t read, is a modern take on Romeo and Juliet, only this time Juliet meets and falls in love with Romeo after he’s already dead. It is a tale about the power of love to induce positive change and tear down walls even in trying times — of learning to see others as individuals, looking past their superficial group characteristics, and recognizing, even accepting, differences. But all is not moonlight and roses. Life, if one can call it that, among the living and the dead is hard; and even in the end, one cannot eschew entirely a hardnosed realism, as there are some too far gone even for love to heal.

Julie, played by Aussie Teresa Palmer, is the daughter of the military leader (John Malkovich) of an authoritarian, walled compound that houses perhaps the last remaining settlement of living human beings. R, played by Nicholas Hoult, is a zombie who spends his days wandering aimlessly around an airport and occasionally feasting on the flesh of the living. He’s a little off as far as zombies go, in ways you’ll have to see for yourself.

The two meet one fateful day when Julie is out on a pharma-salvage mission with a group of her peers and R is leading a pack of zombies in a hunt for their next meal. Can these two star-crossed lovers make it work? Will the living give R a chance before putting a bullet in his brain? Will R’s fellow undead refrain from eating Julie’s?

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

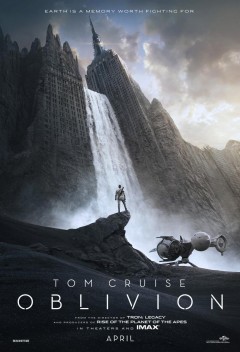

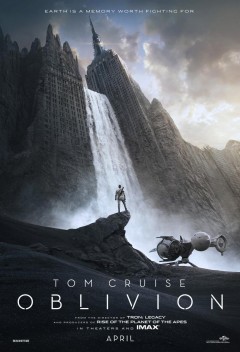

The other day I found myself watching a soccer game. The players were not very good: defenders were constantly out of position, midfielders of the same team were bunching together and stealing the ball from each other, few passes were completed, and those that were often gave the impression of being accidental. Once, the goalie was even caught standing inside the goal when one team took a shot. Fortunately for them, the shot went well wide of the mark, despite the fact that it was taken a mere ten feet from the mouth of the goal.

Notwithstanding the poor level of play, I was enraptured. I cheered, I groaned, I shouted encouragement. I never missed a second of the action. What is more, I had just as eagerly watched the 30-minute practice that had preceded the game. The reason for my enthusiasm was that one of the players was my four-year-old son. There is a lesson there for storytellers of all stripes.

Oblivion is the second opus of director Joseph Kosinski, who also gave us Tron. It is a perfectly average movie on net, with some attributes rising a little above and others sinking a bit below. Of all the changes one might suggest to improve the film, the single most important one would be to populate it with characters we care about. The same thing that turned an hour and fifteen minutes of abject boredom into an engaging experience on a small soccer field in central Ohio would have dramatically improved every single scene of Kosinski’s work.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

It seems that every classic is to have an entourage. The loneliness of such films as Alien, Star Wars, and King Kong is too much to bear for the hearts of movie execs, so companions are made for them. Sequels, prequels, remakes, and spinoffs are what Hollywood does most, though not necessarily best. At times, this proclivity has born sweet fruit. Though sequels are rarely as good as the original, if the original was any good at all, there have been some smashing successes. Even remakes have some achievements to be noted. I am, however, unaware of a prequel or a spinoff whose makers could hold their heads high and proud once their creation hit the silver screen. Oz the Great and Powerful, a prequel to the 1939 classic The Wizard of Oz, is unable to break out of this trend and be the first.

Set some years before the events of Victor Fleming’s work, it tells the tale of the wizard himself, a travelling magician from Kansas making a meager, day-to-day living. A magician is a trickster, of sorts, and Oscar Diggs (James Franco) has a character well suited to it. Though one gets the sense that at his core he is not entirely amoral, he lies to friend and stranger alike. He lusts after money and women, whom he tricks for his own benefit.

It is this very duplicity in his nature that gets him running from trouble and sets him on course for Oz. After flirting with the wife of a circus strongman, he escapes the enraged husband in a hot air balloon just as a tornado begins to ravage the landscape. As happened in the original film to Dorothy, the tornado transports him to the magical Land of Oz. There, he meets Theodora, a witch played by Mila Kunis.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

Steven Soderbergh’s latest film, Side Effects, uses the modern themes of high finance and psychiatry to fashion a plot that grows increasingly riveting as the story unfolds. The script features some very classic elements of tale-spinning executed with adroitness, while the director’s realistic, subtle style makes a great complement. What is more, there are all kinds of themes and subtext of interest to the libertarian, who will nod knowingly throughout the film, even if the filmmakers take a neutral position and give no indication whether they are too.

There are a number of plot points that pull the rug out from underneath the viewer, turning points that completely alter what the movie appears to be about. By the time we find out the true nature of the story, a few of these twists have already occurred. This makes it difficult to know how to summarize the film.

The movie is a suspense thriller of sorts, but distinct from most thrillers in the way it is executed. Soderbergh does not use slow-motion, close-up cuts or insistent music to belabor points and hit the audience over the head. He films and edits in a simple, subtle style. This is not to say that the movie is hard to follow, but Soderbergh does treat us like adults. When a character is dissimulating, for instance, this fact will not be spoonfed to the viewer. There will be no close-up of the actor’s face as he makes the kind of expression that has come to be a clue that he is tricking someone, the kind of expression that, if a person made it in real life, would instantly give him away.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

Cloud Atlas, a movie based on the novel of the same name, is a bundle of stories with interconnecting threads meant to form a greater pattern, a message to the viewer. We are all in this together, we conclude by the movie’s end. Sometimes we are nice to each other, and sometimes we are not, but either way our actions resonate into the future, even as they were partly shaped by actions from the past that resonated into the present. The filmmakers are successful in creating this pattern, but as a piece of entertainment and a storytelling vehicle, the movie itself achieves only limited success.

Each story of the larger tale is engaging by itself. That is, the scenario created is interesting enough and worthy of its own movie. The scenes are shot well, and thoughtfully, and the worlds, ranging from far in the past to far in the future, are imaginative conceptions where many other stories might take place. Given this format, it is difficult to summarize the film, which is just as well because watching it becomes more of an exercise in identifying themes and spotting parallels than in following a plot.

The cutting between stories is done in such a way as to prevent momentum from accruing. While I have read many good books that switched between multiple characters to good effect, these books had the characters as part of the same story, so that an advance in the plot of one character’s story had immediate and important ramifications for the other characters, wherever they were in their story arcs. Each chapter usually had a beginning, middle, and end, as if it were its own short story, and finished with some sort of hook to make you regret leaving that character.

In Cloud Atlas, a character in one tale might compose music that another character hears decades later, but the connection is only important for the theme; it has no bearing on the obstacles to be overcome in the endeavor to reach a goal. With only a handful of exceptions, the characters in later times are not even aware of the ones who anteceded them. Imagine taking scenes from Amistad, Blade Runner, Star Wars, Miller’s Crossing, and Three Days of the Condor and mixing them together into one film. As far as the plot goes, this is almost exactly how isolated each story is from the others, how little they have to do with one another.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

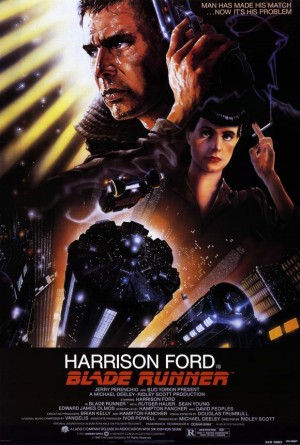

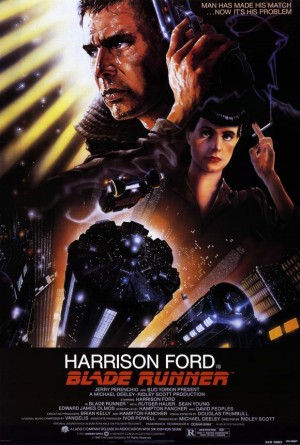

There are many elements of science fiction that find their way into stories that are not science fiction. Many times, enthusiasts of the genre will try to claim these works as part of the family. Atlas Shrugged and 1984 are examples. The same thing happens, only more frequently, with noir. Sometimes, the mere presence of a morally ambiguous protagonist is enough for a piece to be so labeled.

Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, however, is a rare work — quite possibly unique — that may fit both bills. While perhaps not classically noir, there is no denying a strong noir presence, and its science fiction credentials are beyond question, what with the flying cars and androids, called replicants, and off-world colonies. As a devotee of both genres, I quite naturally am a fan of the director’s third film, but watching it is an experience both frustrating and pleasant. It is a good movie, but not the great one it could have been.

Alien, Scott’s second feature, is a masterpiece whose best form made it to the silver screen. One simply cannot imagine a better version. Blade Runner, however, is a movie whose perfect version was never realized, whose potential was never reached. That mirage of the ideal Blade Runner intrudes on my thoughts every so often, and I find myself reaching for the DVD, thinking that perhaps this will be the viewing where I get it, where I notice that missing part or make that important connection.

It never works out that way. As usually happens in life, experience trumps hope. The movie simply is not as good as it ought to have been, and the reason is the plot. This is all the more tragic given that Philip K. Dick, in the novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, had already provided a first-rate plot that was later diluted over multiple drafts of the screeenplay.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

A director returns, after several years and more than one lackluster attempt with other kinds of movies, to a genre he redefined. He had some little known but modestly successful works before his big breakthrough, but since then he just has not been the same man who gave us such an epic, fantastic spectacle full of industry-defining special effects, wonderful music, thrilling action, and, above all, a new world to explore with characters we wanted to accompany. Special effects have come a ways since his magnum opus was crafted, and if used correctly they have the potential to enhance the visual experience even more than before. What could possibly go wrong?

Peter Jackson’s latest project is out in theaters. I wish I could say it was called The Hobbit, but honesty compels me to report that the name is actually The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. The reason for the alteration is that The Hobbit will be brought to us not as a short adventure thrill ride, in keeping with the pace and feel of the source material, but rather will be extended into a movie trilogy that, when finished, will outlast a typical BBC miniseries. The motive behind this sort of reverse editing, whereby Tolkien’s notes were raided for things to stuff into the story and plump it up, is Mr. Jackson’s belief that we are stupid enough to triple his box office take if he triples the number of movies to be made from the story. He is probably right. I know I bought my ticket.

Even with his triumphs Jackson had a tendency to let a project get bloated. The best example, I believe, is the sudden barrage of scenes that hit us in The Two Towers right as we should be, could be, would be cruising toward the third act if a drawn-out and apocryphal love story were not fed to us by way of flashbacks, many in a languid, dreamy style that makes one wonder if one has just witnessed something shot wholly in slow motion. When Jackson had over 1,000 pages of material to convert to nine hours of footage this was an annoyance. With The Hobbit, he has fewer than 300 pages to make into nine hours and the filler has now surpassed the beef in the hotdog.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post