In 2010, John Ringo published the first book of the Troy Rising trilogy. Titled Live Free or Die, it is a story on a grand scale, a great symphony of a book but by an author who probably should stick to bagatelles. Though it started well and had my interest, it was a chore to get through most of it. There was enough creativity and verve for a short story, but by the end these had faded and I was glad to be finished.

It is the kind of story I imagine Ted Nugent would enjoy reading. Filled with gun-toting, rugged individuals who thrive on infuriating the Thought Police and composing odes to capitalism, the book might almost seem libertarian until one realizes just how besotted with militarism and American exceptionalism the author is. I have no problem with a man a bit rough around the edges, a touch short on couth and decorum, but Ringo at times goes beyond that into deliberate callousness, especially as regards sex and race.

There are many sensitive liberals who both need and deserve a little rattling from time to time, if only for our amusement, but there are just as many conservatives who could use a dose of circumspection, introspection, and nuance. I am tempted to suggest we lock Ringo in a room with his diametric opposites, to see if there might be a mutually beneficial rubbing off, but I am afraid someone would end up dying.

Live Free or Die begins with an alien race that establishes a portal in our solar system. They have no goals except to neutrally manage the portal, but the next race that appears is bent on imperial control of Earth. They begin by destroying some major cities and then demanding tribute. Though this species, the Horvath, is technologically backwards in comparison to other civilizations in the galaxy, they are yet far ahead of humans.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

Steven Soderbergh’s latest film, Side Effects, uses the modern themes of high finance and psychiatry to fashion a plot that grows increasingly riveting as the story unfolds. The script features some very classic elements of tale-spinning executed with adroitness, while the director’s realistic, subtle style makes a great complement. What is more, there are all kinds of themes and subtext of interest to the libertarian, who will nod knowingly throughout the film, even if the filmmakers take a neutral position and give no indication whether they are too.

There are a number of plot points that pull the rug out from underneath the viewer, turning points that completely alter what the movie appears to be about. By the time we find out the true nature of the story, a few of these twists have already occurred. This makes it difficult to know how to summarize the film.

The movie is a suspense thriller of sorts, but distinct from most thrillers in the way it is executed. Soderbergh does not use slow-motion, close-up cuts or insistent music to belabor points and hit the audience over the head. He films and edits in a simple, subtle style. This is not to say that the movie is hard to follow, but Soderbergh does treat us like adults. When a character is dissimulating, for instance, this fact will not be spoonfed to the viewer. There will be no close-up of the actor’s face as he makes the kind of expression that has come to be a clue that he is tricking someone, the kind of expression that, if a person made it in real life, would instantly give him away.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

Cloud Atlas, a movie based on the novel of the same name, is a bundle of stories with interconnecting threads meant to form a greater pattern, a message to the viewer. We are all in this together, we conclude by the movie’s end. Sometimes we are nice to each other, and sometimes we are not, but either way our actions resonate into the future, even as they were partly shaped by actions from the past that resonated into the present. The filmmakers are successful in creating this pattern, but as a piece of entertainment and a storytelling vehicle, the movie itself achieves only limited success.

Each story of the larger tale is engaging by itself. That is, the scenario created is interesting enough and worthy of its own movie. The scenes are shot well, and thoughtfully, and the worlds, ranging from far in the past to far in the future, are imaginative conceptions where many other stories might take place. Given this format, it is difficult to summarize the film, which is just as well because watching it becomes more of an exercise in identifying themes and spotting parallels than in following a plot.

The cutting between stories is done in such a way as to prevent momentum from accruing. While I have read many good books that switched between multiple characters to good effect, these books had the characters as part of the same story, so that an advance in the plot of one character’s story had immediate and important ramifications for the other characters, wherever they were in their story arcs. Each chapter usually had a beginning, middle, and end, as if it were its own short story, and finished with some sort of hook to make you regret leaving that character.

In Cloud Atlas, a character in one tale might compose music that another character hears decades later, but the connection is only important for the theme; it has no bearing on the obstacles to be overcome in the endeavor to reach a goal. With only a handful of exceptions, the characters in later times are not even aware of the ones who anteceded them. Imagine taking scenes from Amistad, Blade Runner, Star Wars, Miller’s Crossing, and Three Days of the Condor and mixing them together into one film. As far as the plot goes, this is almost exactly how isolated each story is from the others, how little they have to do with one another.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

There are many elements of science fiction that find their way into stories that are not science fiction. Many times, enthusiasts of the genre will try to claim these works as part of the family. Atlas Shrugged and 1984 are examples. The same thing happens, only more frequently, with noir. Sometimes, the mere presence of a morally ambiguous protagonist is enough for a piece to be so labeled.

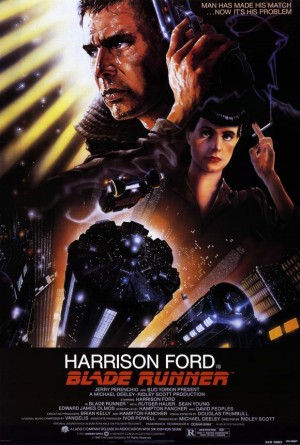

Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, however, is a rare work — quite possibly unique — that may fit both bills. While perhaps not classically noir, there is no denying a strong noir presence, and its science fiction credentials are beyond question, what with the flying cars and androids, called replicants, and off-world colonies. As a devotee of both genres, I quite naturally am a fan of the director’s third film, but watching it is an experience both frustrating and pleasant. It is a good movie, but not the great one it could have been.

Alien, Scott’s second feature, is a masterpiece whose best form made it to the silver screen. One simply cannot imagine a better version. Blade Runner, however, is a movie whose perfect version was never realized, whose potential was never reached. That mirage of the ideal Blade Runner intrudes on my thoughts every so often, and I find myself reaching for the DVD, thinking that perhaps this will be the viewing where I get it, where I notice that missing part or make that important connection.

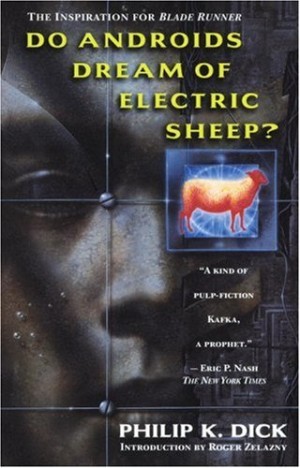

It never works out that way. As usually happens in life, experience trumps hope. The movie simply is not as good as it ought to have been, and the reason is the plot. This is all the more tragic given that Philip K. Dick, in the novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, had already provided a first-rate plot that was later diluted over multiple drafts of the screeenplay.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? is probably Philip K. Dick’s most famous work, given that it was turned into one of the most respected science fiction films of all time. I do not hold to the absolutist opinion that the book is always better than the movie, but after one read of the book and many viewings of the movie, I am inclined to say that, in this instance, the book is at least as good and in some respects is better.

Rick Deckard, along with numerous other unfortunate souls, has been left behind on Earth, an unhealthy wasteland from which anyone of means has migrated. He is the number two man assigned to retire rogue androids who try to pass themselves off as human. The androids, however, prefer to remain alive.

Deckard makes a modest living, but when the number one guy is nearly killed by an android, he assumes the responsibility to retire a group of six of them, seeing in the job an opportunity to make some much-needed cash. Insert canned line about things not going as planned. Insert second canned line about the job being more than he bargained for.

As I expected, the clownish dialogue and behavior, unnecessarily detailed descriptions and lengthy back stories injected into scenes immediately after a character’s introduction — the slipshod method by which so many authors introduce and develop their characters — is absent. Instead, we meet people who feel and act real, and we come to know them as we would anyone else: by how they act, what they say, and what is said about them. They move about in an exotic land but act in accordance with their human goals and abilities.

What I found surprising was how good the plot was. There is a satisfying quantity and variety of dramatic interactions, various obstacles to overcome, a sufficiently grand and tense third act… everything an eager reader could hope for. I did not expect a poorly wrought narrative, but given some of the difficulties I found in The Man in the High Castle, I thought that maybe character and setting were Dick’s strengths, not plot. The movie, as good as it is, strikes one as underplotted, and I assumed this was due to a deficiency on the book’s part.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

A director returns, after several years and more than one lackluster attempt with other kinds of movies, to a genre he redefined. He had some little known but modestly successful works before his big breakthrough, but since then he just has not been the same man who gave us such an epic, fantastic spectacle full of industry-defining special effects, wonderful music, thrilling action, and, above all, a new world to explore with characters we wanted to accompany. Special effects have come a ways since his magnum opus was crafted, and if used correctly they have the potential to enhance the visual experience even more than before. What could possibly go wrong?

Peter Jackson’s latest project is out in theaters. I wish I could say it was called The Hobbit, but honesty compels me to report that the name is actually The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey. The reason for the alteration is that The Hobbit will be brought to us not as a short adventure thrill ride, in keeping with the pace and feel of the source material, but rather will be extended into a movie trilogy that, when finished, will outlast a typical BBC miniseries. The motive behind this sort of reverse editing, whereby Tolkien’s notes were raided for things to stuff into the story and plump it up, is Mr. Jackson’s belief that we are stupid enough to triple his box office take if he triples the number of movies to be made from the story. He is probably right. I know I bought my ticket.

Even with his triumphs Jackson had a tendency to let a project get bloated. The best example, I believe, is the sudden barrage of scenes that hit us in The Two Towers right as we should be, could be, would be cruising toward the third act if a drawn-out and apocryphal love story were not fed to us by way of flashbacks, many in a languid, dreamy style that makes one wonder if one has just witnessed something shot wholly in slow motion. When Jackson had over 1,000 pages of material to convert to nine hours of footage this was an annoyance. With The Hobbit, he has fewer than 300 pages to make into nine hours and the filler has now surpassed the beef in the hotdog.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post

This review is part of a series covering each installment of the serialized novel Higher Cause, written by John Hunt and published by Laissez Faire Books. To catch up, start with the announcement, the book’s link-rich table of contents, and the first review.

It has been a long trip. Twenty-two weeks, sixty chapters plus a prologue and an epilogue. With this week’s installment, John Hunt’s Higher Cause finally comes to an end.

We had a lot of adventure, saw a lot of character and relationship arcs, experienced some mystery and intrigue, and all the while saw a libertarian society in operation. It struggled to survive in the midst of statism, full of dedicated men who not only believed in a libertarian philosophy but were willing to live it and work hard to achieve it. It would be nice to see more works of this sort.

The books virtues, as I have mentioned before, are the imagination that went into the concept and the overall grasp of a story arc. The writing is generally solid and Hunt manages to competently weave together a rather complex tale.

It is my opinion that the dialogue could be improved and that certain sections of the prose could be deleted to good effect. At times, there was a tendency to over-explain things.

In addition to the above, and with the story now behind us, there are other aspects I would like to point out as needing strengthening. For starters, the separate story strands could have been synchronized a little better. For most of the novel, they complimented each other and crisscrossed back and forth quite nicely, but things came loose a touch at the end.

[continue reading…]

Help Promote Prometheus Unbound by Sharing this Post